The Modification of Decrees in the Original Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court

abstract. Interstate disputes in the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction often implicate long-term interests, such as state boundaries or rights to interstate bodies of water. Decades after the Court issues a ruling in an original jurisdiction case, the parties may ask the Court to revise its decree. However, the Court’s current standard for considering modification requests is underdeveloped and inconsistent. With the rights of entire state populations on the line, there are strong considerations on both sides: interests in ensuring that an original jurisdiction decree is sufficiently final, but also in ensuring that in the event of significant, unexpected changes, the Supreme Court can modify its decree. This Note surveys all original jurisdiction cases since 1791 and concludes that the Court revises its decrees far more often than its purported standard would suggest. It then proposes a clearer finality principle that accurately reflects its behavior and effectively accommodates the competing needs for finality and justice. Tracing the historical development of decree modifications from the days of Lord Francis Bacon through the merger of law and equity and onward to the Court’s recent institutional-reform cases, this Note argues that the general finality principle that has developed through these cases in the district courts is normatively and descriptively superior to the one-off test announced by the Supreme Court in original jurisdiction cases.

author.Yale Law School, J.D. expected 2017. I offer warm thanks to Professor Eugene Fidell, Jane Ostrager, and Joseph Nawrocki for their role in helping this Note take root; to Professor Nicholas Parrillo for detailed and careful comments that helped it grow; and to Jennifer Yun and the editors of the Yale Law Journal for their exemplary pruning. Most importantly, thanks to my ever-supportive family: Jeffery, Misty, Alyssa, Joshua, and Julia.

Introduction

The Constitution reserves the power to invoke the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court—to ask the Court to swap its lofty appellate musings for the gritty, fact-laden inquiries of a trial court—to a few parties whose dignitary interests are thought to require it.1 These parties are sovereigns and their representatives: states; the United States; and in theory—though no longer in practice—ambassadors, public ministers, and consuls.2 The few parties who possess this power rarely invoke it,3 and even then the Court may decline to exercise its jurisdiction if the “seriousness and dignity of the claim” is insufficient.4 When the Court allows an original jurisdiction case to go forward, however, the resulting litigation—like the embattled sovereigns—proceeds on an unusually long time horizon. The case may turn on events that occurred before a state joined the union,5 an interstate compact formed before the ratification of the U.S. Constitution,6 or a royal proclamation that predates the Declaration of Independence.7 Once the Supreme Court decides an original jurisdiction case, its judgment can spur decades of additional litigation.8 This longevity,9 combined with the specificity of many decrees,10 can produce decrees that no longer meet the parties’ needs decades later.11 In such circumstances, the Court faces a question on finality: when should it modify its own judgments?

Before addressing this normative question, however, one first needs a clear empirical understanding of the Court’s current practice. To investigate this practice, I surveyed all 263 original jurisdiction cases over the Court’s two-century history. I categorized them based on the nature of the dispute and the resolution of each case and analyzed how often the Court has modified its decrees.12

The results of my survey demonstrate that the Supreme Court’s words on finality have not matched its actions. In Arizona v. California,13 the principal case on point, the Court claimed to be guided in its exercise of discretion by “principles of res judicata.”14 But its announced doctrine does not accurately describe its approach across the original docket. The data suggest that (1) the Court frequently modifies decrees, and (2) the Court is more likely to modify decrees in cases where dynamic fact patterns are likely to arise. Building on these findings, the Note proposes an alternative descriptive account: instead of applying principles of res judicata, as Arizona v. California purports to do, the Supreme Court in practice has used a flexible test like the one that district courts have long applied when considering requests for decree modifications.15

Moreover, the Court should continue to apply its flexible test to requests for decree modifications in original jurisdiction cases. The test dates back to Lord Francis Bacon’s ordinances. Though it has changed somewhat over the centuries, the standard has survived the test of time in broad strokes because it takes into consideration the Court’s concern with “general principles of finality and repose”16 and balances that concern against case-specific facts that may justify modification.

The Court, then, should explicitly identify its flexible standard as the test that it has applied and will continue to apply in its original jurisdiction cases. Aligning the Court’s purported test with its actual approach to requests for decree modification will provide litigants with clearer and more accurate guidance than the Court’s announced—yet ignored—doctrine of “principles of res judicata.”

The issue of finality in the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction has received no scholarly attention until now. In general, the literature on the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction is relatively sparse.17 Scholars have addressed a number of questions peculiar to the original jurisdiction, such as whether the Court’s extensive delegation of power to special masters is troubling18 and whether Congress or the Court has the power to prescribe the procedures original jurisdiction litigants must follow.19 Some commentators have examined procedural questions, such as what the Court would do if a Justice recused himself or herself and the vote was tied,20 or how the early Court conducted a jury trial.21 However, no scholar has squarely addressed the finality of judgments in original jurisdiction cases.

This Note begins to fill that gap. Section I.A briefly describes the history of the Court’s original jurisdiction. It then offers a procedural outline for a modern original jurisdiction case. This procedure is characterized by “gatekeeping”—the Supreme Court’s calculated effort to protect itself from time-consuming original jurisdiction cases—and provides the background for the Court’s stated interest in finality in original decrees. In the same vein, Section I.B enumerates courts’ and litigants’ interests in finality and highlights the heightened stakes of finality in the original jurisdiction.

Part II compares the quintessential original jurisdiction case—the dispute over an interstate boundary—with water rights cases. In boundary disputes, finality was once thought essential to prevent war. On the other hand, as water rights cases illustrate, changed circumstances sometimes outweigh finality interests, making decree modification essential. The case studies in this Part show that the Supreme Court modifies decrees more frequently in water rights cases, which have dynamic fact patterns, than in boundary disputes, where the facts remain relatively static.

Having examined the potential for variation in decree modifications in original jurisdiction cases, Part III considers the standard for modifying decrees in original jurisdiction cases that the Court announced in Arizona v. California.22 There, the Court declared that it would exercise its discretion and apply “principles of res judicata” and “general principles of finality and repose” to judgments in original jurisdiction cases.23 The precise meaning of these phrases is unclear, especially when taken together. The case therefore does not give litigants and the future Court sufficient guidance for deciding whether to modify decrees. Res judicata is a common-law doctrine that takes effect when a court enters a final judgment.24 Later, if a party to the original proceeding brings the same claim again, the claim is precluded. It seems anomalous that the Court would apply this intercase concept to a motion to modify a decree within the same case. At the same time, res judicata is the strongest finality principle on the menu: when it applies, the trial court lacks power to entertain the new claim. By invoking “principles of res judicata,” then, the Court seems to suggest that litigants should expect motions for modification to be denied.

If the Court truly applies such a strict finality principle, then decree modifications should be relatively rare, and they should not differ based on the type of original jurisdiction case at issue. Part IV compares these predictions with the Court’s actual practice. Specifically, I report the findings of a survey of all cases on the Court’s original jurisdiction docket from constitutional ratification to the end of 2015. The results indicate that decree modifications are relatively common: of ninety-seven original jurisdiction cases with decrees, decrees have been modified in twenty-eight cases.25 Moreover, the frequency of modification has varied depending on the type of case at issue. The data show that the Court is unlikely to modify its decree in cases establishing interstate boundaries but has regularly modified decrees in water rights cases. These findings suggest that the Court, in assessing motions for modification, has not remained faithful to the res judicata principle it endorsed in Arizona v. California.

The Court used a second phrase in Arizona v. California as well, seemingly interchangeably with “principles of res judicata”: the Court said it would apply “general principles of finality and repose” to determine whether to modify a decree.26 Part V argues that, if defined by reference to trial courts’ approach to decree modifications throughout history, “general principles of finality and repose” may provide an effective, flexible test for decree modification in original jurisdiction cases. The Part starts with a historical account of the development of motions for decree modification, from Lord Bacon’s ordinances in 1619 through the law-equity merger and Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(b)(5). It argues that the Court should apply most of the principles that have been developed in that longstanding line of jurisprudence, rather than “principles of res judicata.”27 The Note concludes with a summary of the test that has emerged from this line of cases and an application of the standard to different types of original jurisdiction cases.

I. the original jurisdiction of the supreme court

A. History and Procedure

To understand the Supreme Court’s strongly stated commitment to finality in original jurisdiction decrees, one must first understand why the Court considers the original jurisdiction to be unique. The original jurisdiction’s history and its modern procedure, which has evolved in reaction to that history, provide valuable context.

In the colonial era, the power to adjudicate disputes between colonial governments was vested in the Privy Council.28 The Articles of Confederation conferred that power on the Congress, with an intricate rigmarole for selecting a panel of between five and nine commissioners to try the case.29 This provision was rarely exercised30 and appears to have resulted in only one final judgment.31 The Supreme Court later suggested that both the Privy Council and the Articles of Confederation had been ineffective in resolving interstate-boundary disputes, which had continued since the first colonial settlements.32

The Constitutional Convention took a different approach. An early draft proposed dividing the power to adjudicate disputes between the Senate and the Supreme Court, with the former deciding boundary disputes and the latter all others.33 However, the Framers ultimately decided to consolidate the power in the Supreme Court alone.34 The initial plan to divide this power between the Senate and the Supreme Court suggests that the delegates at the Constitutional Convention foresaw that interstate disputes would arise in contexts other than boundary disputes.

As anticipated at the Constitutional Convention, the Court has handled a panoply of other types of original jurisdiction cases,35 but the canonical case has remained the interstate-boundary dispute.36 In these cases, the Court has weighed historical evidence about British land grants or tidal movements to set a precise interstate boundary. It once appointed commissioners to mark the line; today it uses GPS. Another common dispute, a close analogue to the boundary case, is the dispute between a state and the federal government over title to land, such as coastal submerged land; the resolution of such cases can determine important property rights, such as a party’s right to drill for oil.37 A third common category of suits, particularly over the past fifty years, might be broadly termed “federalism” disputes: these involve state challenges to the constitutionality of federal statutes, regulations, or policies. For example, South Carolina sued to enjoin enforcement of the Voting Rights Act,38 and Georgia sued to prevent the federal government from impounding certain federal financial assistance to the states.39 Finally, water rights disputes are also becoming increasingly common and relevant.40 In some cases, statutes or compacts govern the rights to an interstate body of water;41 in other cases, water rights are “equitably apportioned” by the Court under a highly discretionary standard.42

In addition to the more common types of disputes, there are a variety of rarely seen cases, including interstate claims for nuisance43 and breach of contract,44 disputes about taxes and escheats of unclaimed property,45 and state challenges to the legality of other states’ laws,46 among others.47

Initially, the Supreme Court heard every interstate dispute brought before it, dismissing cases only for the reasons a trial court would dismiss (such as lack of jurisdiction).48 This practice is unsurprising given the ancient legal principle that a court with jurisdiction must exercise it.49 However, the Court has increasingly declined to exercise its jurisdiction, initially for cases that could be brought in a different forum and later even for cases that could be argued nowhere else.50 In Ohio v. Wyandotte Chemicals Corp.,51 the Court defended this discretionary approach. The Court explained that it was an appellate body foremost, and that it was unsuited for fact-finding.52 Therefore, the Court requires parties to seek the Court’s permission before litigating a case in the original jurisdiction.53 Today, the merits stage of an original jurisdiction dispute is preceded by a gatekeeping stage that bears an uncanny resemblance to petitions for writs of certiorari.54 These “motions for leave to file a bill of complaint” are commonly denied.55

The Court denies motions for leave to file a bill of complaint more commonly in some types of cases than in others. In particular, the Court will frequently deny motions for leave to file in federalism, tax, contract, and criminal-law cases, as well as cases challenging the constitutionality of state laws.56

If the Court grants the motion for leave to file a bill of complaint, the plaintiff may file the complaint, which is followed by the defendant’s answer and possible counterclaims as in other trial courts.57 After the pleading stage, however, the Court generally delegates the bulk of the fact-intensive argument to a special master.58 After the parties have presented evidence and argued the issue before the special master, he or she issues a report to the Court, and the parties file exceptions. In this respect, a special master is similar to a magistrate judge in the federal district court. The Court has plenary power to review all issues of law or fact, although it once empaneled a jury for determining the issues of fact.59 The Court has always been empowered to handle cases at law and in equity,60 so it can grant monetary judgments, equitable decrees, or both. In the case of a decree, that decree will generally continue in perpetuity. Years later, parties may return to request modifications of the decree.61

B. The Importance of Finality in the Original Jurisdiction

When the Court considers a motion for decree modification, it claims to apply general finality principles and, in particular, principles of res judicata.62 At first glance, this might seem nonsensical. Res judicata, a common-law doctrine, prevents the same parties from bringing the same claim again in a different lawsuit.63 In other words, res judicata normally does not apply to a motion to modify a decree in the same case. An investigation of the importance of finality in the original jurisdiction sheds some light on why the Court might articulate such a strong principle of finality, even if the stated doctrine would not usually apply.

1. State Parties and Additional Litigation Costs

In the original jurisdiction, the risk of wasted resources is particularly salient because state and federal coffers carry the burden of litigation.64 The Court may be especially interested in protecting the pocketbooks of taxpayers, who likely do not care whether a particular gas station is in North Carolina or South Carolina.65 This incentive provides a policy rationale for discouraging relitigation of original jurisdiction cases in particular. Furthermore, given that the Court has frankly expressed that it is ill-suited for fact-finding,66 there are even stronger doubts than usual about whether more litigation would produce the “correct” outcome.

In addition to the usual costs of litigation, original jurisdiction cases involve the fees and expenses of court-appointed officials, such as special masters, commissioners, and river masters, which often must be paid by both parties. The Court might be particularly perturbed at taxing court costs against a party who has already “won.”67

2. Judicial Resources

Even if the states and their taxpayers are willing to bear the costs of this litigation—as might be the case when drought-plagued states sue for water rights—modifying decrees also expends judicial resources. This cost is far more salient in the Supreme Court than in the district courts, given that the Court is a bottleneck institution, hearing oral argument in less than one percent of the cases for which petitions for writs of certiorari are filed.68

In appellate cases, the Supreme Court can protect its calendar by instituting gatekeeping procedures and circumscribing the parties with limits on filing length, oral argument time, and so forth. In original jurisdiction cases, however, the Court is a trial court and must consider and rule on each issue of fact. The Justices are conscientious about this; the Court’s opinion in New Jersey v. New York conjures up a mental image of The Nine peering over one another’s shoulders as they scrutinize hoary maps to discern whether a certain pier was built on filled land.69 In reality, much of the fact-finding is delegated to a special master,70 but the Court must rule on every exception to the special master’s report. And one cannot rule out the possibility—however remote—of a party demanding a jury trial.71

Such fears animated the Court’s decision to introduce discretionary denials of motions for leave to file bills of complaint.72 The Court might ascribe its use of a particularly strong finality principle to its need for a similar gatekeeping function after a case has been decided.73

3. Reliance Interests

A third type of cost in modifying decrees is that there are often reliance interests. Whether in district courts or the original jurisdiction, these reliance interests are especially important when all taxpayers have acted in reliance on the prior decree.74 Furthermore, in the original jurisdiction, more than money is at stake: reliance can come in the form of legislation by a state government. A state that has built a dam or power plant based upon its understanding of a water rights decree has sunk both financial and political capital into the project. In the event of a decree modification, it may lack sufficient political support to revisit the issue.

4. Encouraging Settlement and Avoiding Enforcement Issues

The Supreme Court’s preference for negotiation over adjudication in original jurisdiction cases also provides a reason to adopt a strong finality standard.75 Because original jurisdiction cases involve litigation between sovereigns, they carry an unusually high risk of noncompliance.76 Consent decrees, in which parties settle and ask courts to memorialize their agreement with an injunction carrying the force of law,77 avoid the expenses of a lengthy trial. But more importantly, compromise makes it less likely that the Court will have to independently enforce the decrees.

Frequently modifying consent decrees when one party is unhappy with its prior agreement would discourage settlement negotiations78 and increase the risk that the Court would face an enforcement standoff in the future. Furthermore, consent decrees need not contain findings of fact or conclusions of law, so it may be even more difficult for the Court to recognize whether there has been a relevant change since the entry of the decree that might justify a departure from its terms.79

***

While these reasons make finality especially important in original jurisdiction cases, a strict finality principle is not a panacea. The Supreme Court must consider and rule on each modification request. Even a strong finality principle will not fully ameliorate concerns about litigation costs and judicial resources. A strong finality principle, moreover, has its own costs, especially in cases affecting entire states. The next Part illustrates how changed circumstances may justify modification of decrees despite the Court’s stated finality principle and the principle’s policy rationales.

II. comparing relevance of changed circumstances in boundary disputes and water rights cases

The contrast between boundary disputes and water rights cases—two types of frequently litigated original jurisdiction cases—illustrates that the Court has deviated from its stated strict finality principle in certain categories of cases but not others. A careful examination of these two types of cases also shows that the Court has engaged in a more traditional inquiry of examining changed circumstances in facts and law when deciding whether to modify a decree.

A. Boundary Disputes and the Specter of War

The Court almost never modifies boundary-related decrees.80 Consider Rhode Island v. Massachusetts, a boundary-dispute case from 1838,81 in which Massachusetts asked the Court to ignore the pre-Revolution series of charters and letters that set the disputed boundary because to do otherwise would be to grant Great Britain enduring power inconsistent with the American states’ hard-won independence.82 These concerns did not persuade the Court, which held that such a long-standing boundary should not be disturbed.83 In considering this case, the Court was confronted with factors unique to boundary determinations. Most importantly, border conflicts carry with them the specter of armed invasion.84 Therefore, the finality of borders is essential to protecting peace. Inasmuch as states would contemplate war over any original jurisdiction dispute, boundaries are particularly likely to cause war because they implicate a primal sovereign right to the soil.85 In contrast, disputes over water rights generally do not provoke the same sovereignty concerns. Moreover, water rights cases are a modern phenomenon,86 and, Texas separatists notwithstanding,87 interstate war is not a modern concern.88

Furthermore, in some original jurisdiction disputes, such as water rights cases, the governing principle is “equitable apportionment.”89 When adjudicating boundary disputes, on the other hand, the Court has announced that equitable factors are not relevant.90The underlying rationale seems to be that boundaries are set by historical accident, rather than through a weighing of equities. If the Court were to revise these historical dictates, even for good reason, it would be impermissibly poaching a state’s territory. In one illustrative case, the Court rejected a special master’s suggestion that it bend a boundary around a building, even though drawing a state boundary through the building would inconvenience all involved.91

A final unique aspect of boundary cases is that compromises are far less straightforward in such cases than in other original jurisdiction cases.92 Boundaries determine jurisdiction; they implicate a state’s very power to act. For this reason, the Court takes a formalist approach to boundaries instead of weighing equities. This limit on the Court’s power might, a fortiori, restrict parties’ abilities to compromise in boundary cases. The rationale might be compared to the principle that parties may not stipulate to a court’s subject-matter jurisdiction; similarly, states may not stipulate into existence their sovereignty over a particular patch of soil. Furthermore, boundary compromises in an original jurisdiction case might be seen as an attempt to impinge upon the province of Congress: ordinarily, such compromises would be done through the Compacts Clause.93 For these reasons, consent decrees in boundary cases are on shaky ground.

The “principles of res judicata” to which the Court alluded in Arizona v. California might seem well-suited to boundary dispute cases. As a descriptive matter, boundary-case decrees are rarely altered. As a normative matter, this approach is defensible: if states cannot compromise and equities were never involved in setting boundaries in the first place, the most efficient path to dispute resolution might be a binding, unassailable decree.94

B. Water Rights and Changed Circumstances

Water rights cases are not like the canonic boundary-dispute cases: they afford the possibility of compromise and have not historically invoked fears of interstate war. For these reasons, the Court has balanced equities in these cases and frequently modified decrees when changed circumstances warranted the rebalancing of those equitable factors.95

Nebraska v. Wyoming96illustrates the Court’s balancing of equities in water rights cases and its resulting frequent modification of decrees. In 1934, a thirsty Nebraska sued Wyoming in the original jurisdiction (with Colorado later impleaded as a defendant), seeking equitable apportionment of the North Platte River.97 The Court ruled that prior appropriation would serve as a loose guiding principle,98 and it entered a decree.99 The decree enjoined Colorado and Wyoming from storing or diverting more than a specified amount of water, set priorities among various canals and federal reservoirs, and explicitly apportioned the flows in a particularly contentious stretch of river during the irrigation season.100 The Court reserved jurisdiction to modify the decree as it saw fit.101

The parties returned to the Court soon after, with a joint motion to modify the decree in light of a new dam and reservoir.102 The Court entered the modified decree without a whisper about res judicata.103 In 1995, more than three decades later, Nebraska returned with requests for additional relief related to tributaries and groundwater that were hydrologically linked to the North Platte, and for more detailed apportionment during the nonirrigation season.104 The Court, after citing its reservation of jurisdiction in the decree, explained, “The parties may . . . not only seek to enforce rights established by the decree, but may also ask for ‘a reweighing of equities and an injunction declaring new rights and responsibilities . . . .’”105 The Court allowed some claims to go forward, including one claim to modify the decree to prevent Wyoming from performing certain developments that would “upset the equitable balance”106 established in the decreeand another to enjoin the use of a new technology—increasingly pervasive groundwater pumping, which the Court characterized as “a change in conditions posing a threat of significant injury.”107

After the Court allowed these claims to go forward, the parties reached a comprehensive settlement. The Court modified the prior decree in accordance with that settlement in 2001.108 Though Arizona v. California was on the books by then, the Court did not express a concern that it lacked jurisdiction due to principles of res judicata.

Nebraska v. Wyoming demonstrates the importance of equities in the water rights context and the significance of the parties’ ability to compromise. In one of the consent decrees, the Court even allowed a modification of its jurisdiction-saving clause that barred Colorado from requesting additional modifications for a period of five years, as if the Court’s jurisdiction were something a state could bargain away.109 Surely such a permissive regime is not what “principles of res judicata” suggests.110

In Wisconsin v. Illinois, another case with intriguing decree modifications that bear no resemblance to res judicata, the Court was forced to take drastic action to protect public welfare.111 In 1929, Wisconsin sought relief from the Court, claiming that Chicago was pumping water from Lake Michigan for sanitary purposes, to the detriment of the Great Lake states.112 The Court held this diversion illegal, but acknowledged the defendant’s public-health concerns.113 Within a year, pursuant to a special master’s findings, the Court entered a decree requiring Chicago to gradually decrease its water use over the following eight years.114 In 1933, after the special master reported that Illinois was unjustifiably failing to take steps to follow the decree, the Court expanded the decree to order Illinois to raise the necessary funds.115 Then, in 1940, the Court learned that substantial amounts of sewage sludge had accumulated.116 The parties stipulated that Chicago would be permitted ten days of greatly increased water usage to attempt to dislodge the muck, and the Court modified its prior decree in accordance with that stipulation.117 But with a hydrological network as complex as the Great Lakes Basin, another emergency followed two decades later. The Mississippi River fell to a dangerously low level, causing navigational emergencies, and the Court ordered a temporary modification of the decree to help alleviate the crisis.118 That same day, the Court referred the matter to an individual justice, Justice Burton, “with power to act” on behalf of the whole Court.119 The modification was again extended in a similar fashion as the crisis continued.120

In both Nebraska v. Wyoming and Wisconsin v. Illinois, the Court displayed a willingness to modify decrees when changed circumstances justified modification.121 It did not believe that it was prevented from doing so because of res judicata, nor did it mention that it was guided in its decision making by principles of res judicata.122 As discussed above, res judicata is an absolute doctrine,123 and it does not allow the weighing of equities. If the Court had applied principles of res judicata, it likely would have refused at least some of the modifications requested in these two cases.

Moreover, applying a strict finality principle would have been normatively undesirable in the cases described above. These cases demonstrate the importance of the Court’s choice of finality principles. In each dispute, enforcing the old decree in the face of changed circumstances would have been contrary to the purpose of the original decree, or led to consequences unforeseen and unintended at the time of adopting the original decree. If the Court had applied principles of res judicata and chosen not to allow Chicago to dislodge its sewage sludge, substantial public-health consequences could have followed. Similarly, if the Court had rigidly clung to its prior decree despite new irrigation technologies in Nebraska v. Wyoming or despite unforeseen hydrological changes in Wisconsin v. Illinois, the economic implications would have been far-reaching. These examples also show that because unforeseeable changes in circumstances are particularly likely in water rights cases, a strict finality principle is much less desirable than in boundary-dispute cases. This means that not only does the Court modify decrees at different rates in different types of cases, but also that the stated approach of the Court in original jurisdiction cases is neither workable nor equitable, as discussed in Part III.

III. the supreme court’s purported approach to original jurisdiction decree modification

The previous two Parts have enumerated the finality interests at stake and illustrated that decree modifications are nevertheless essential in some cases. This Part turns to the Supreme Court’s attempt to balance these issues in Arizona v. California, the only case in which the Court has discussed its approach to requests for modification of decrees in original jurisdiction cases in detail.124 The case began in 1952 when Arizona invoked the Court’s original jurisdiction over a dispute with California regarding the states’ rights to use the waters of the Colorado River;125 Nevada, Utah, and New Mexico also joined the suit.126 The United States intervened in the case to seek water rights on behalf of certain federal lands, including Indian reservations.127 As in most original jurisdiction cases, the Court referred the case to a special master.128

The Arizona v. California Court ruled that water rights in the Colorado River were governed by the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928129 and that prior to that Act, the United States had reserved water rights for the Indian reservations.130 Because the reservations had already been created as of the date of the Boulder Canyon Project Act, the reservations’ water rights were “present perfected rights” and therefore received priority.131 The Court adopted the special master’s findings with respect to precise acreages and entered a decree apportioning water rights in the river.132 The Court included a generalized jurisdiction-saving clause, Article IX of the decree, which would later give rise to its discussion of finality:

Any of the parties may apply at the foot of this decree for its amendment or for further relief. The Court retains jurisdiction of this suit for the purpose of any order, direction, or modification of the decree, or any supplementary decree, that may at any time be deemed proper in relation to the subject matter in controversy.133

In 1978, the United States joined several tribes in moving for additional water rights for the reservations, conceding that the federal government had done a poor job representing their interests earlier in the litigation.134 The Court referred the motion to a newly appointed special master, Elbert P. Tuttle, a senior judge of the Fifth Circuit.135 Before Tuttle, the states argued that the motion was barred by res judicata;136 the tribes and the federal government countered by invoking a different finality principle: law of the case.137

Law of the case is a traditional principle of common law. But unlike res judicata, it is “a discretionary rule of practice,” not a “uniform rule” of procedure.138 It is based on the notion that “when an issue is once litigated and decided, that should be the end of the matter.”139 In Supreme Court jurisprudence—appellate and original—law of the case has very little substance; it is mainly an expression of courts’ general preference for finality.140 Special Master Tuttle reasoned that Article IX “contains no limiting language,”141 so the Court must have great discretion over whether to modify its prior decree. Special Master Tuttle observed that law of the case principles should govern the Court’s discretion.142 Thus, he concluded, law of the case was the best finality principle to apply in this sort of case.143

This is not a particularly persuasive argument, and Tuttle himself admitted uncertainty about the correct principle to apply.144 The Court declined to adopt his reasoning, explicitly avoiding the contentless law of the case doctrine: “To extrapolate wholesale law of the case into the situation of our original jurisdiction, where jurisdiction to accommodate changed circumstances is often retained, would weaken to an intolerable extent the finality of our Decrees in original actions.”145 The Court denied the tribes’ motion in the interest of finality.146 In its opinion, the Court claimed that it had applied “principles of res judicata” to determine whether it would allow relitigation of the issue.147

The Court’s reference to “principles of res judicata” might be read in two ways. First, the Court might simply mean that the correct finality principle to apply is the principle of res judicata. In some cases on its appellate docket, the Court has used the phrase “principles of res judicata” in this way.148 Passages in Arizona v. California similarly suggest that the Court is applying res judicata in full force.149 For instance, the Court found that it did not have to balance equities.150 Is that because res judicata, or a similar principle, had removed the Court’s power to balance equities? No, the Court explained: “[Article IX] grants us power to correct certain errors, to determine reserved questions, and if necessary, to make modifications in the Decree.”151

The Court’s acknowledgment that it has power to make modifications suggests that it meant “principles of res judicata” in a more general sense. This reading is supported by a different phrase the Court used: “[Article IX] should be subject to the general principles of finality and repose, absent changed circumstances or unforeseen issues not previously litigated.”152 This phrase, though similarly lacking in precedent, suggests a degree of discretion and of equity-balancing that res judicata would forbid. Part V will attempt to give content to this phrase by arguing for a superior finality principle for decree modification that also reflects the Court’s practice.

IV. when does the supreme court actually modify its decrees?

In light of the ambiguity discussed above surrounding the Court’s invocation of “principles of res judicata,” it seems safe to conclude that the Arizona Court failed to articulate a clear finality principle. If the Court was articulating a strict finality principle, one would expect to see relatively few decree modifications; furthermore, because res judicata does not take equities into account, adhering to a strict principle of res judicata would mean that the frequency of decree modifications would not vary much from one case type to the next.

However, as we have already seen in the water rights examples,153 the Court does not always follow a strict finality principle in practice. In this Part, I resolve these empirical questions of how often and when the Court modifies its own decrees by expanding the analysis to the entire universe of original jurisdiction cases. I first updated the lists of original case activity begun by a student author in 1959 and continued by retired Maine Supreme Court Justice, and sometime Special Master, Vincent L. McKusick in 1993.154 With a complete list of every original case, I divided these cases into nineteen categories by subject matter.155 For each case, I noted the dispositive actions taken by the Court and classified the case based on its resolution. These resolutions are: motion for leave to file denied; dismissed (including withdrawn); unknown resolution or long inactive; ongoing; temporary relief only; merits (no decree); decree: never modified; and decree: modified.156

As Appendix A demonstrates, the Court disposes of different cases in different ways. In some categories, such as federalism, constitutionality of state laws, interstate contracts, and criminal law, the majority of claims are over before they even begin because the Court usually denies leave to file a bill of complaint.157 In other categories, such as interstate boundaries, water rights, and federal-state title disputes, the Court almost never denies leave to file.

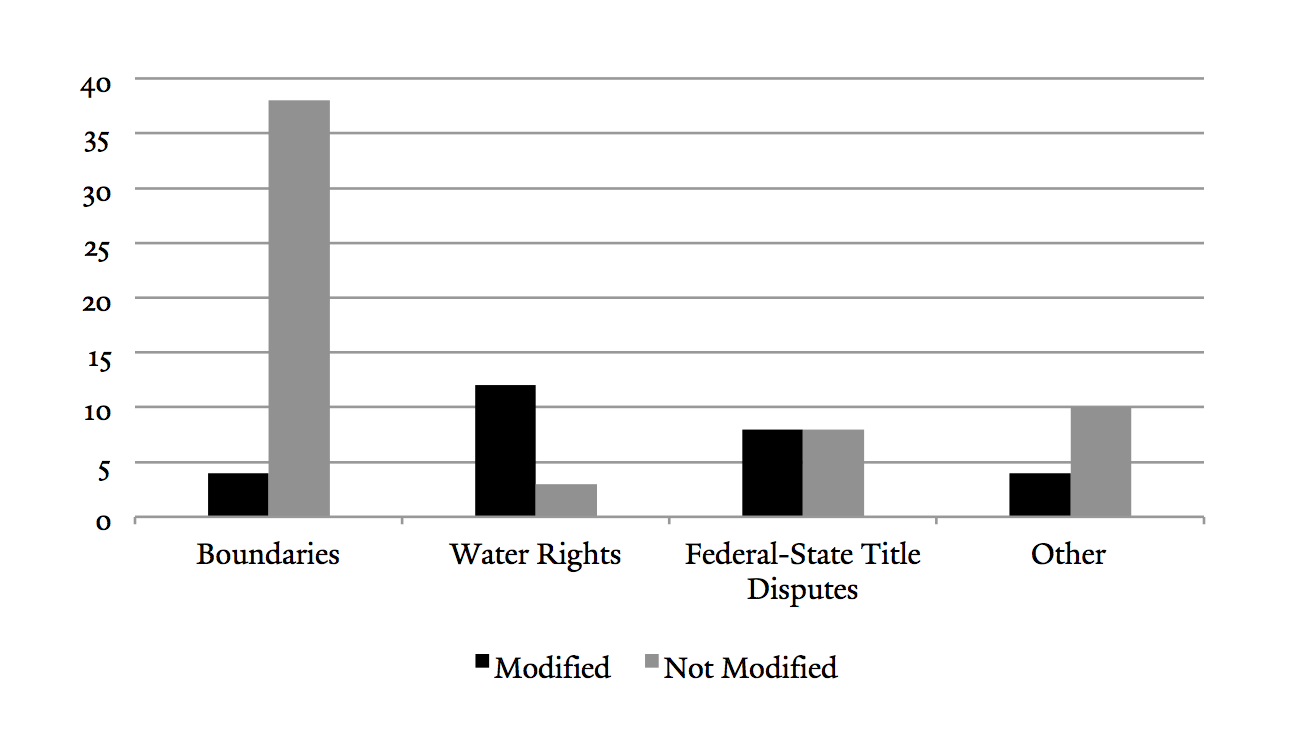

To more closely examine the finality of judgments, I focused on cases that resulted in at least one decree. I divided such cases into two groups: cases that resulted in a decree that has remained final and cases that resulted in a decree that has since been modified, replaced, or supplemented. The results are striking.158 The Court has entered decrees in forty-two interstate-boundary cases, but has modified only four of them. The Court has entered decrees in sixteen federal-state title dispute cases, and has modified eight of them. In water rights disputes, the Court has entered decrees in fifteen cases and has modified twelve of them. In all other categories, it has entered a total of fourteen decrees and has modified four of these decrees.These results are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

decree modifications by case type

These data are inconsistent with the notion that the Court has applied a res judicata-like finality principle to requests for decree modification. First, the Court frequently modifies decrees. Out of 263 total cases, the Court has entered decrees in ninety-seven cases. In twenty-eight of these ninety-seven cases—nearly one-third—the Court has modified a decree.

Furthermore, these data take a relatively strict definition of “modify.” For instance, in several boundary cases, the Court entered a decree establishing an interstate boundary and then entered another decree decades later requiring that the boundary be remarked because the old markings had faded. In some cases, the second decree appointed commissioners to mark the boundary based on where the first commissioners had done so—rather than in accordance with the original boundary determination. Technically, this could be read as a decree modification, but I chose to categorize such cases as decrees with no modification. Even under this strict definition, thirty-two percent of all decrees were modified.159

Moreover, the rate at which the Court modifies decrees varies across different categories of original jurisdiction cases. In other words, the Court is disproportionately willing to modify decrees in some types of cases and disproportionately unwilling to do so in others. Part V, building on this finding, argues that some types of cases involve circumstances that justify re-considering a decree more than others. Whatever principle guides the Court’s decision-making in these cases, it does not resemble res judicata.

There is one additional wrinkle to consider: could it be that the Court’s invocations of res judicata are protective, designed to ward off litigants who might otherwise seek modification? The Court has expressed a need to guard itself against the drain on resources that the original jurisdiction produces: motions for leave to file bills of complaint are a good example of this preference.160 Perhaps the Court’s behavior does not align with its language because it has announced a rule that is designed to be as discouraging as possible to parties who would otherwise seek decree modification. If so, there might be some value in that subterfuge, but a misalignment between the Court’s statements and its actions could eventually provoke skepticism and distrust. The following Part assumes that the Court hopes to prescribe a standard that is consistent with the Court’s behavior.

V. locating “general principles of finality and repose”: from lord bacon to rufo

The data described in Part IV indicate that the Court does not actually apply principles of res judicata consistently and uniformly. Moreover, as the case studies in Part III suggest, this may be a good thing: the Court often has good reasons for revisiting its judgments. In search of a superior standard for modifying prior decrees, I trace the history of finality principles and explain what “general principles of finality and repose” should mean in the context of original jurisdiction cases.161

A. Finality of Judgments: The Flexibility of Equity

For centuries, courts have tried to develop standards for when they will reconsider their judgments.162 The ancient division between law and equity permeates this history. Although law and equity have been nominally merged, the history of modifications in equity courts provides helpful guidance for choosing a principle for decree modification in the original jurisdiction.

Traditionally, at law, English and American judges retained power to modify their judgments until the expiration of the term at which the judgment was entered;163 thereafter, parties could seek modification only under limited circumstances through a petition for a writ of error coram nobis.164 In equity, judges similarly retained power to modify a decree until it was “enrolled”; thereafter, a petitioner would need to request a bill of review.165

The difference between finality principles at law and in equity is illustrated in the Court’s explanation of final judgments and congressional authority to change them. In Plaut v. Spendthrift Farm, Inc.,166 the Court held that Congress may not reverse the judiciary’s final disposition of a case because Article III “gives the Federal Judiciary the power, not merely to rule on cases, but to decide them.”167 A significant corollary to this rule, first articulated in Wheeling & Belmont Bridge, is that Congress does have the authority to change substantive law in a way that forces a court to modify a prospective decree.168 In other words, although an injunction is “a final judgment for purposes of appeal, it is not the last word of the judicial department.”169 Rather, the issuing court may be called upon to construe or enforce the decree at some time in the future; because of this “continuing supervisory jurisdiction,” modifications to the underlying law allow modifications of the decree itself.170 Therefore, a judgment at law is immune from congressional challenge, but in equity, changes of law can justify decree modifications.

For more than a century, the distinction between law and equity persisted in federal common law.171 But in 1938, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure nominally merged law and equity, subsuming the legal writ of error coram nobis and the equitable bill of review into a single “motion for relief from judgment.”172 Nevertheless, the merger did not rob history of its significance.173 In the district courts, prospective decrees are still subject to modification if enforcement would be inequitable.174

B. From Bacon to Horne: Development of the Flexible Test in Equity

Tracing the development of the standard for modifying judgments in cases at equity illuminates the rationale behind the flexible standard that trial courts have adopted and that the Supreme Court should also adopt for its original jurisdiction cases. When the old equity courts were presented with bills of review, they asked two questions:175 first, whether reconsideration is justified at all; second, if so, whether the court will exercise its equitable discretion in modifying the decree. The first inquiry was more formulaic: a party had to fall into one of several prescribed categories to qualify for a bill of review.176 The second involved the court’s traditional equitable discretion.177 This Section concentrates on the first step in the analysis: the threshold showing that a party must make in order to convince the court to reconsider its prior weighing of the equities, which varies depending on the finality principle at issue.178

As a foundational matter, a court always retains supervisory jurisdiction over a final decree;179 the defendant remains bound to obey under penalty of contempt. Thus justice requires that the court retain jurisdiction to modify that decree if it becomes inequitable. This intuition dates back to Lord Bacon’s ordinances in 1619.180 Bacon, the Lord Chancellor at the time, considered the same question we consider today: when should the court exercise this jurisdiction to modify a decree? He propounded the following guidelines:

No decree shall be reversed, altered, or explained, being once under the great seal, but upon bill of review: and no bill of review shall be admitted, except it contain either [(1)] error in law, appearing in the body of the decree without farther examination of matters in fact, or [(2)] some new matter which hath risen in time after the decree, and not any new proof which might have been used when the decree was made: nevertheless [(3)] upon new proof, that is come to light after the decree made, and could not possibly have been used at the time when the decree passed, a bill of review may be grounded by the special license of the court, and not otherwise.181

Lord Bacon’s tripartite test set forth broad categories that are still relevant to courts’ decree modification inquiries today.

The first ground, “error in law,” is generally left to appeals courts today, but this notion is still reflected in the common-law power of courts to correct their own clerical errors.182 Another progeny of this category is the idea that courts have inherent power to modify their own decrees to make their terms unambiguous.183 The third ground for review—newly discovered evidence that was not available at trial—has remained a distinct category.184

The second ground, “new matter,” is the most capacious and the most contentious. By the middle of the twentieth century, courts recognized two broad types of new matter that could ground an argument for decree modification: changes of law and changes of fact.185

Changes of law may require courts to reconsider a decree.186 For instance, in the Wheeling & Belmont Bridge case, the Supreme Court determined that the erection of a bridge was unlawful and decreed that the bridge must be destroyed.187 Then Congress specifically blessed the bridge by statute.188 The defendant asked the Court for release from its obligations under the decree, and the Court acquiesced.189 This result is not surprising: it is aligned with our separation-of-powers understanding that the political branches should be able to repeal and update our laws without being hemmed in by ossified decrees. This outcome is less obvious when the decree was entered by consent, with no determination of liability. However, the Supreme Court has held that even in such cases, given that bargaining was accomplished in the shadow of the law, the removal of the statute casting that shadow requires reevaluation of the underlying decree.190

In addition to changes of law, “new matter” can also arise from changes of fact.191 Original jurisdiction examples abound—avulsion may have caused an interstate boundary to freeze in place;192 a new technology may have called into question a court’s earlier equitable apportionment of water.193 When changes in fact happen after the entry of decrees, trial courts consider these changes as possible justifications for reweighing the equities.194

In the early twentieth century, the Supreme Court’s appellate case law sharply curtailed this approach with what has become known as the “grievous wrong” test. The test was crafted by Justice Cardozo in the 1932 case United States v. Swift & Co., and it set a very high bar: “Nothing less than a clear showing of grievous wrong evoked by new and unforeseen conditions should lead us to change what was decreed after years of litigation with the consent of all concerned.”195 Scholars and lower courts gradually pushed back against Swift’s stringent requirements.196 In New York State Association for Retarded Children, Inc. v. Carey,197 the Second Circuit was confronted with the challenge of applying Swift to an institutional reform case. Judge Friendly found that because of their complexity and longevity, institutional reform decrees would be particularly unmanageable under the “grievous wrong” test. He explained, “The power of a court of equity to modify a decree of injunctive relief is long-established, broad, and flexible.”198

The Supreme Court was eventually convinced by Judge Friendly’s arguments. In Rufo v. Inmates of Suffolk County Jail, the Court described a flexible test for district courts to apply when considering requests for modifications of their decrees.199 The Court noted that “the ‘grievous wrong’ language of Swift was not intended to take on a talismanic quality, warding off virtually all efforts to modify consent decrees.”200 Emphasizing “the need for flexibility in administering consent decrees,”201 the Court noted that “a sound judicial discretion may call for the modification of the terms of an injunctive decree if the circumstances, whether of law or fact, obtaining at the time of its issuance have changed, or new ones have since arisen.”202 The Court added that in the time since the Court adopted the “grievous wrong” test, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure had been adopted, and Rule 60’s standard is liberal.203

Rufo lists situations in which a change of facts could justify a decree modification: (1) “changes in circumstances that were beyond the defendants’ control and were not contemplated by the court or the parties when the decree was entered”;204 (2) “achieving the goals” of the underlying litigation;205 and (3) advancing the public interest when decrees affect parties not directly involved in the suit and the public’s right to sound operations of institutions.206 Though dressed up in new verbiage and re-christened as the “flexible approach,”207 the test articulated in Rufo instantiates the second category of “new matter” in Lord Bacon’s traditional test.

However, Rufo was not the Supreme Court’s last word on the matter. The Supreme Court revisited the issue of decree modifications in Frew v. Hawkins208and again in Horne v. Flores.209 The reasoning in these cases addressed decrees in the specific context of institutional reform litigation against state agencies. In Horne, this focus on institutional reform litigation is underscored by the Court’s three reasons for applying a particularly flexible test in such cases.210

The first of these concerns is the frequency with which changed circumstances occur in institutional reform cases.211 Of course, changed circumstances can arise in any case involving a permanent injunction, including in the original jurisdiction. But the flexible test of Rufo sufficiently addresses changes of fact and changes of law. The difference in Horne is that the Court added a third type of change that might justify modification: “new policy insights.”212 This subtle shift evinces the Court’s true concerns, which it also listed explicitly as the second and third rationales for applying a particularly flexible test to institutional reform cases: these decrees shift power from state legislatures to a single federal judge, raising federalism concerns.213 Furthermore, they ossify policy, allowing state actors to bind their successors by failing to defend these suits vigorously.214

The Horne Court’s concerns are not as salient in original jurisdiction cases. Commentators have provided many examples of state actors seeking to bind their successors by acting as “secret plaintiffs” in institutional reform cases.215 By contrast, original jurisdiction disputes are truly adversarial. State officials do not have political incentives to concede to the opposing state more land or more water than it deserves. Federalism concerns are similarly lacking in original jurisdiction decrees. The original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court is unabashedly federalist. The point of the original jurisdiction, ambassadors aside, is to provide a federal forum for interstate disputes.

Given that worries about collusive state actors and federalism concerns are not present in the original jurisdiction, the rationale of Horne does not apply to original jurisdiction cases. Rather, the best reading of Horne is that it changed the test for institutional reform decrees specifically; the better test for decree modifications in original jurisdiction cases is the one articulated in Rufo.216

C. The Finality Rule and Its Application in Original Jurisdiction Cases

A synthesis of this case law demonstrates that when deciding whether to modify a decree, a federal court considers essentially the same factors that Lord Bacon announced in 1619.217 The Court should consider adopting this approach, both to increase doctrinal coherence and to more accurately describe how the Court determines whether to modify its decrees.

Under this traditional approach, which elaborates Lord Bacon’s standard, a court asks the following questions:218 First, is there a clerical error on the face of the decree, or an ambiguity that renders the decree unenforceable as written? Second, has newly discovered evidence arisen that could not have reasonably been discovered in time to move for a new trial?219 Finally, has a “new matter” arisen since trial that makes continued prospective enforcement of the decree inequitable?

This last question, in turn, is further elaborated under Rufo. To answer the third question, a court would first inquire whether the underlying law has changed or, more commonly in original jurisdiction cases, whether there has been a change in facts that unexpectedly makes compliance (1) substantially more onerous to litigants; (2) detrimental to the public interest; or (3) less effective in vindicating a protected party’s rights.220 If any of these prongs is satisfied, or if the parties consent, then the court would reweigh the equities to determine if a modification is justified.221

The Court should explicitly adopt this test for four reasons. First, this test more accurately articulates the finality principle that the Supreme Court should and does apply in the original jurisdiction docket. Second, this test can account for the difference in decree modification rates in different types of cases, as observed in Part IV. Third, it is not a mechanical test, as equity is not a mechanical doctrine.222 This test provides content to the “general principles of finality and repose” mentioned in Arizona v. California; it is far more specific than “principles of res judicata”;223 and it has centuries of history backing it. Finally, unlike res judicata, this test properly balances competing interests in finality and justice.

A few examples illustrate the test’s effectiveness.

1. Water Rights

Recall Wisconsin v. Illinois,224 the Chicago sewage case. The accrual of a large amount of active sludge was a textbook case of “new matter.” If the Court had applied the Rufo test, it would have found that there was a change in facts that unexpectedly made compliance substantially more onerous to the defendant, justifying a reweighing of equities. The second decree modification, due to an anomalous drop in the Mississippi River, would have also been justified under the Rufo test: it is a perfect example of unanticipated changed circumstances in which unmodified enforcement of the decree would have been detrimental to the public interest.

Similarly, in Nebraska v. Wyoming, the case involving a new irrigation technology, the Court agreed to reweigh the equities, but did not actually reach that second step before the parties settled.225 The Court’s justification for allowing argument on the reweighing of equities was that there had been a change of facts—the development of this new irrigation technology—that made prospective application of the decree inequitable by making the decree less effective at vindicating the plaintiff’s rights. This justification is also consistent with the Rufo articulation of Lord Bacon’s standard.

2. Boundary Disputes

In Louisiana v. Mississippi, the Supreme Court entered a decree in 1906 establishing the contested boundary between the two states, including on the Mississippi River.226 Between 1912 and 1913, the river avulsed. This rapid change in land mass around the river froze the interstate boundary as a matter of law, meaning that the boundary no longer moved with the navigable channel of the Mississippi River. The parties returned to the Court, as the old decree was no longer specific enough to describe the boundary around the area of the avulsion. In other words, under the Rufo test, a change in facts decreased the old decree’s efficacy in vindicating the litigants’ rights. Therefore reconsidering the prior decree was justified.

In Kansas v. Missouri, the Court was forced to modify a decree because of a change in law.227 After the full resolution of the case on the merits and the entry of a decree, the litigants reached a compromise that was blessed by Congress pursuant to the Compacts Clause.228 In accordance with Wheeling & Belmont Bridge, this meant that the old decree could no longer be prospectively enforced. It satisfies the “change of law” branch of the “new matter” prong, so under the above test, the Court should have modified the decree to conform to the interstate compact. This is exactly what the Court did.

Notwithstanding these examples, it is worth noting that these cases—wherein “new matter” warrants a decree modification—are rare among boundary-dispute cases. Intuitively, and especially compared to water rights cases, unforeseeable changes in circumstances that would affect state borders are limited. This explains the low modification rate for boundary-dispute cases noted in Part IV.

3. Federal-State Title Disputes

United States v. California229 involved a dispute regarding title to the lands underlying certain bays and estuaries extending out into the Pacific Ocean. The Supreme Court articulated a standard and entered a broad decree regarding how the boundary should be drawn, reserving the issue of drawing that boundary with precision.230 As oil drilling made the boundary question particularly pressing in some areas, the parties returned to the Court, asking for precise lines in those regions.231 However, Congress then entered the fray, passing the Submerged Lands Act, “vest[ing] in California all the interests that were then thought to be important.”232 The case fell silent.

When drilling technology again improved, so that submerged lands even further off the coast could be drilled, the dispute revived. The Court modified its decree to provide more specificity, but also to incorporate legislative changes—both the Submerged Lands Act itself and, with respect to certain technical issues, changes in the international law on what constituted inland waters.233 The question of whether to grant a modification in this case was another example of applying the Rufo articulation of Lord Bacon’s inquiry—specifically, there had been a change in the underlying substantive law on which the old decree rested.

4. Other Cases

The Rufo standard works also for the wide variety of miscellaneous original jurisdiction cases the Court handles apart from boundaries, water rights, and title disputes. For example, in New Jersey v. City of New York, an interstate nuisance case, New Jersey sued New York City for dumping garbage into the Atlantic, causing it to end up on the shores of New Jersey.234 New York City’s defense was that it had always dumped garbage into the Atlantic.235 New Jersey prevailed: the Court ordered that New York City construct incinerators for its garbage and cease dumping garbage by a date certain, or else pay a daily fine to New Jersey.236 New York City, due to financial constraints, did not meet the deadline.237 The Court awarded damages to New Jersey but modified its decree to set a new date for compliance.238

This application for a decree modification, though not discussed using any particular standard, could also have been examined through the Rufo articulation of the “new matter” inquiry. Specifically, the Court could have asked whether there had been a change in facts that unexpectedly made compliance substantially more onerous on the defendant. It is not clear whether that is what was actually done in this case—it occurred during the Great Depression, so perhaps there truly was an unexpected change in New York City’s finances. If not, perhaps the modification should not have been granted. Instead, the Court might have found that New York City was violating the decree, albeit not contemptuously, and ordered it to comply by a new date certain or be held in contempt of court. Regardless of what the Court may have done, the inquiry could have been conducted under a relatively transparent, replicable test. Instead, the Court’s standard for modification was unspoken and its rationale opaque.

Conclusion

The Court’s current standard for modifying decrees in original jurisdiction cases, insofar as it has one, confuses litigants more than it guides them and does not reflect the Court’s practice. “Principles of res judicata” are not applied in any other context, and res judicata is not a reasonable doctrine to apply to motions for decree modification. Because of the longevity and the shifting equities in many original jurisdiction cases, a more balanced and nuanced test is required.

Instead of reinventing the wheel, the Supreme Court should decide whether to modify its decrees under the same two-step inquiry that has guided courts of equity since the seventeenth century. This standard would properly channel the Court’s discretion, without being excessively restrictive (like principles of res judicata) or excessively directionless (like law of the case). By explicitly adopting such a test, the Court would bring clarity to its decision-making process and guide litigants as they navigate the rarely travelled path of the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

For the Appendices to this Note, please see the PDF version.

See Henry Wade Rogers, The Essentials of a Law Establishing an International Court, 22 Yale L.J. 277, 280 (1913) (“De Tocqueville said: ‘In the nations of Europe, the courts of justice are only called upon to try the controversies of private individuals; but the Supreme Court of the United States summons sovereign powers to its bar.’”); see also Charles Warren, The Supreme Court and Sovereign States 6-8 (1924). In addition to states and the United States government, ambassadors, public ministers, and consuls can also invoke the original jurisdiction, see U.S. Const. art. III, § 2, cl. 2, but in only two such cases has such an invocation produced a decision on the merits, see Casey v. Galli, 94 U.S. 673 (1877); Jones v. Le Tombe, 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 384 (1798); see also Note, The Original Jurisdiction of the United States Supreme Court, 11 Stan. L. Rev. 665, 718-19 (1959). Although Indian tribes are sovereign as well, they do not have the power to invoke the Court’s original jurisdiction. See Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. 1, 25 (1831) (acknowledging that the Cherokee Nation is sovereign but refusing to grant it the right to sue in the original jurisdiction); see also Principality of Monaco v. Mississippi, 292 U.S. 313 (1934) (holding that a foreign state cannot bring suit against an American state in the original jurisdiction, at least without that American state’s consent); John C. Sullivan, Considering the Constitutionality of Nonstate Intervenors in Original Jurisdiction Actions, 86 Notre Dame L. Rev. 2219, 2224 (2001) (exploring the Court’s inconsistent positions over time as to when nonstate parties may intervene in original jurisdiction cases).

There have been 263 cases in the original jurisdiction resulting in some form of published action by the Court. See Vincent L. McKusick, Discretionary Gatekeeping: The Supreme Court’s Management of Its Original Jurisdiction Docket Since 1961, 45 Me. L. Rev. 185, 216-42 (1993); Note, supra note 2, at 901-19; infra Appendix B.

Illinois v. City of Milwaukee, 406 U.S. 91, 93 (1972); see also McKusick, supra note 3, at 202 (“The substantial set of gatekeeping rules that the Supreme Court has developed adds up to making its original jurisdiction for practical purposes almost as discretionary as its certiorari jurisdiction over appellate cases.”).

See, e.g., New Jersey v. New York, 526 U.S. 589, 589-90 (1999) (considering, for the purpose of fixing the location of an interstate boundary at Ellis Island, details as narrow as whether a pier had been built on filled land before entering a mathematically precise decree in accordance with GPS-based testimony).

One original jurisdiction case, Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803), is celebrated, though not for its original jurisdiction significance specifically. But see Akhil Reed Amar, Marbury, Section 13, and the Original Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, 56 U. Chi. L. Rev. 443 (1989) (considering implications specific to original jurisdiction).

See, e.g., Anne-Marie C. Carstens, Lurking in the Shadows of Judicial Process: Special Masters in the Supreme Court’s Original Jurisdiction, 87 Minn. L. Rev. 625 (2002); see also Cynthia J. Rapp, Guide for Special Masters in Original Cases Before the Supreme Court of the United States (Oct. 2004) (on file with author).

See, e.g., Stephen R. McAllister, Can Congress Create Procedures for the Supreme Court’s Original Jurisdiction Cases?, 12 Green Bag 2D 287 (2009); Stephen R. McAllister, Congress and Procedures for the Supreme Court’s Original Jurisdiction Cases: Revisiting the Question, 18 Green Bag 2d 49 (2014); see also Kansas v. Colorado, 556 U.S. 98, 109-10 (2009) (Roberts, C.J., concurring) (arguing that the Exceptions Clause demonstrates that the Supreme Court, not Congress, has the power to set witness fees in original jurisdiction cases).

Although most of the principles developed in this line of cases are applicable to the original jurisdiction, there are exceptions. A few recent decree-modification cases appear to have loosened the test even further in light of federalism concerns that arise in institutional-reform litigation. See, e.g., Horne v. Flores, 557 U.S. 433 (2008); Frew ex rel. Frew v. Hawkins, 540 U.S. 431 (2004). For reasons explained below, these federalism concerns are not as salient in original jurisdiction cases. See infra Part V.

Cheren, supra note 30, at 115; see 1 Hampton L. Carson, The History of the Supreme Court of the United States with Biographies of All the Chief and Associate Justices 75-76 (1904); 1 Julius Goebel, Jr., History of the Supreme Court of the United States: Antecedents and Beginnings to 1801, at 189 (1971); Akhil Reed Amar, The Two-Tiered Structure of the Judiciary Act of 1789, 138 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1499, 1561 n.222 (1990) (“[U]nder the Articles of Confederation the only suit between states ever to reach judgment before the nascent national tribunal established to hear such cases was in fact litigated by a member of Congress. Members of Congress also appeared before the national tribunal in both of the only two other state suits that came before the tribunal, but never reached judgement [sic].” (citations omitted)).

Rhode Island v. Massachusetts, 37 U.S. (12 Pet.) 657, 724 (1838); see also 1 James Brown Scott, Judicial Settlement of Controversies Between States of the American Union: An Analysis of Cases Decided in the Supreme Court of the United States 3 (1919) (“[T]he 9th Article was a prophecy of better things, rather than a realization; for only one case was decided and only one commission was appointed under this procedure; and when the government under the Constitution succeeded the government under the Articles there were controversies between eleven States concerning their boundaries, to mention only differences of this nature, unsettled between the States.”).

U.S. Const. art. III, § 2, cl. 2; see also Principality of Monaco v. Mississippi, 292 U.S. 313, 328-29 (1934) (“[T]he States by the adoption of the Constitution, acting ‘in their highest sovereign capacity, in the convention of the people,’ waived their exemption from judicial power. The jurisdiction of this Court over the parties in such cases was thus established ‘by their own consent and delegated authority’ as a necessary feature of the formation of a more perfect Union.”). The Court was also given original jurisdiction over another type of case: those involving ambassadors, public ministers, and consuls. U.S. Const. art. III, § 2, cl. 2. But this provision has not been invoked successfully in more than two centuries. See supra note 2 and accompanying text.

See, e.g., Oysters vs. Atlanta; How Exactly Will the Supreme Court Decide How To Divide Water in the ACF Basin?, SustainAtlanta (July 4, 2015), http://sustainableatlantaga.com/2015/07/04/oysters-vs-atlanta-how-exactly-will-the-supreme-court-decide-how-to-divide-water-in-the-acf-basin [http://perma.cc/WP3J-G9UX].

See Nebraska v. Wyoming, 325 U.S. 589, 618 (1945) (“Apportionment calls for the exercise of an informed judgment on a consideration of many factors. Priority of appropriation is the guiding principle . . . . [However, the many factors involved] indicate the nature of the problem of apportionment and the delicate adjustment of interests which must be made.”).

See, e.g., Louisiana v. W. Reserve Historical Soc’y, 465 U.S. 1018 (1984) (denying the motion for leave to file a bill of complaint in a replevin action); Justices Reject Documents Battle Between Ohio Group, Louisiana, Tol. Blade, Feb. 22, 1984, at 3 (providing background on the replevin action); see also Massachusetts v. New York, 271 U.S. 65 (1926) (eminent domain); United States v. Minnesota 270 U.S. 181 (1926) (patents).

Id. at 499; see also Mississippi v. Louisiana, 506 U.S. at 76 (1992) (“Recognizing the ‘delicate and grave’ character of our original jurisdiction, we have interpreted the Constitution and 28 U.S.C. § 1251(a) as making our original jurisdiction ‘obligatory only in appropriate cases’ and as providing us ‘with substantial discretion to make case-by-case judgments as to the practical necessity of an original forum in this Court.’”).

See Sup. Ct. R. 17.3; Mississippi v. Louisiana, 506 U.S at 76 (“Recognizing the delicate and grave character of our original jurisdiction, we have interpreted the Constitution and 28 U.S.C. § 1251(a) . . . as providing us with substantial discretion to make case-by-case judgments as to the practical necessity of an original forum in this Court.” (citation omitted)).

See infra Appendix A. The Court recently denied Nebraska’s motion for leave to file a complaint against Colorado for its decriminalization of marijuana. Nebraska v. Colorado, 136 S. Ct. 1034 (2016). Justices Thomas and Alito dissented, arguing that the Court’s discretionary approach to the original jurisdiction “bears reconsideration.” Id. at 3 (Thomas, J., dissenting). This is a significant change of position from prior cases, as Justice Thomas conceded. Id.

Von Moschzisker, supra note 24, at 312 (“[Res judicata] constitutes an absolute bar to a subsequent action . . . .”). Specifically, if the party won the first action, then that party’s subsequent claim will be merged into the initial claim, and only proceedings for the effectuation of judgment will be permitted. If the party lost the first action, then that party’s subsequent claim will be barred. Jack H. Friedenthal et al., Civil Procedure 1213 (11th ed. 2013).

Relitigating an issue already decided by a court is also undesirable in nonoriginal jurisdiction cases. A litigated decree has already required the parties to bear the financial burden of fighting through to a merits decision. Furthermore, it is unclear that additional litigation after a final judgment is worth the added cost. See Richard A. Posner, An Economic Approach to Legal Procedure and Judicial Administration, 2 J. Legal Stud. 399, 445 (1973) (“[T]he expected value of relitigation in enhancing the accuracy of the adjudicative process is (in general) zero.”).

See Stephen R. Kelly, How the Carolinas Fixed Their Blurred Lines, N.Y. Times (Aug. 23, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/24/opinion/sunday/how-the-carolinas-fixed-their-blurred-lines.html [perma.cc/JD52-MSGY] (“[The Carolinas’] two-decade effort [to amicably re-mark their boundary] is not complete, and the fate of a gas station whose pumps have surfaced in the ‘wrong’ state could derail the whole thing. But if they succeed, they might well set an example of comity and cooperation for the rest of our head-butting nation.”).

See Frequently Asked Questions, Sup. Ct. U.S. (2014), http://www.supremecourt.gov/faq.aspx [https://perma.cc/6PG5-KQKP] (estimating that ten thousand petitions for writs of certiorari are filed each year, with oral argument occurring in just seventy-five to eighty cases).

See, e.g, Montana v. Wyoming, 135 S. Ct. 1479, 1479 (2015) (mem.) (“The Master’s Report and submissions of parties indicate that fees and expenses could well exceed any recovery. Parties are therefore directed to consider carefully whether it is appropriate for them to continue invoking the jurisdiction of this Court.”). The Court has allowed settlements even on thorny issues like its own jurisdiction. See infra Section II.B (discussing the Court’s acquiescence in a decree modification that altered the jurisdiction-savings clause it had entered in its earlier decree in Nebraska v. Wyoming, 345 U.S. 981, 981 (1953)).

One case in which such a risk materialized was Virginia v. West Virginia, 220 U.S. 1 (1911). The Court, having been pressed to rule on whether West Virginia owed Virginia a debt based upon certain agreements entered into at the time of West Virginia’s creation, admonished: “Great states have a temper superior to that of private litigants, and it is to be hoped that enough has been decided for patriotism, the fraternity of the Union, and mutual consideration to bring it to an end.” Id. at 36. Instead, a decade of additional litigation ensued, with the Court nearly having to decide whether it could issue a writ of mandamus to compel West Virginia to levy a tax and pay its debt. See Virginia v. West Virginia, 246 U.S. 565 (1918); see also Wisconsin v. Illinois, 289 U.S. 395, 411 (1933) (determining upon the special master’s submission that Illinois was deliberately failing to raise the necessary funds to comply with a decree, the Court enlarged that decree to command that “the state of Illinois is hereby required to take all necessary steps, including whatever authorizations or requirements, or provisions for the raising, appropriation, and application of moneys, may be needed” to comply with this decree); Rhode Island v. Massachusetts, 37 U.S. (12 Pet.) 657, 694 (1838) (“Mr. Justice BARBOUR asked Mr. Hazard, if he could point out any process by which the Court could carry a final decree in the cause into effect, should it make one. For instance, if an application should be made by Rhode Island for process to quiet her in her possession, what process could the Court issue for that purpose?”).