Courts as Managers: American Tradition Partnership v. Bullock and Summary Disposition at the Roberts Court

Introduction

In June 2012, the Supreme Court issued a brief, unsigned order reversing a Montana Supreme Court decision that declined to apply Citizens United v. FEC1 to a state campaign-finance statute.2 Commentators described the Court’s refusal to use American Tradition Partnership v. Bullock to even consider overturning Citizens United3 as “disappointing,”4 “a missed opportunity,”5 and a “mistake.”6 What the decision should not have been was a surprise—not only in its substance, but in its form. American Tradition Partnership is entirely consistent with the Roberts Court’s use of summary disposition—the dispensation of a case without briefing or oral argument—to oversee, manage, and shape the output of lower courts.

In the weeks leading up to the decision, Adam Liptak wrote in the New York Times that the “main question” would be “how the court will reverse the Montana decision.”7 But even that question offered little suspense: American Tradition Partnership presented a perfect vehicle for summary reversal, especially for the Roberts Court, which has not hesitated to use summary disposition to send signals about its legal commitments and priorities.This Essay offers a brief description of summary disposition, presents data on its use at the Roberts Court, and examines three ways in which that Court has used summary disposition. Although the Court has not, contrary to some commentators’ suggestions, used summary disposition more than its predecessors, it has begun to use it differently.

Summary disposition is a procedural innovation, added belatedly and briefly to the Supreme Court rules. The Warren and Burger Courts conducted experiments with the tool—the Warren Court by reversing lower courts without explanation, the Burger Court by providing reasons and opportunities for lower courts to handle their own affairs. The Roberts Court, though, has embraced the tool in two novel ways: remanding cases to lower courts without having identified clear error, and reversing complex, fact-bound cases without having called for briefing. In doing so, the Court has increasingly acted in what this Essay describes as a managerial capacity, potentially to cope with an ever-increasing flow of certiorari petitions. But there may be consequences: a form of judicial carelessness in which summary disposition is used not simply to manage and oversee lower courts’ dockets, but—contrary to tradition and reason—to make new law.

I. Summary Disposition in Theory

Supreme Court Rule 16, which governs the Court’s disposition of petitions for writs of certiorari, states that an appropriate order in any case “may be a summary disposition on the merits.”8 It does not explain when such an order may be appropriate. It does not explain why the Court might issue one. It does not even explain what summary disposition is: what information it contains, what commands it gives, what precedential value it holds. Such questions are left to the Court to work out in practice. The ambiguous role and amorphous boundaries of summary disposition have led to consternation and criticism, both within the Court9 and beyond.10 But the criticism has not halted the practice. Over the last forty years, the Court has relied on three common, if controversial, forms of summary disposition:

Summary orders, which simultaneously grant certiorari petitions and affirm or reverse the judgment below without explanation. These opinions are often issued per curiam (“by the Court,” or unsigned).- Summary opinions, which simultaneously grant certiorari petitions and affirm or reverse the judgment below with explanation, usually a brief discussion of the facts and issues involved. These opinions are also generally issued per curiam.

- Reconsideration orders, which simultaneously grant certiorari petitions, vacate the judgment below, and remand the case to the lower court for “reconsideration”—an order more commonly known as a “GVR,” for “grant, vacate, and remand.”11 Technically, a GVR does “not amount to a final determination on the merits.”12 Rather, it merely indicates that the Court believes that, upon reconsideration, there is “‘a reasonable probability’ that the [lower court] would reject a legal premise on which it relied.”13

Summary disposition at the Supreme Court presents a puzzle. Appellate courts generally act in two capacities: a lawmaking capacity, in which they “announce, clarify, and harmonize the rules of decision employed by the legal system in which they serve”;14 and an error-correcting capacity, in which they “determine if prejudicial errors were committed” in applying those rules to facts.15 But it is well established that the Supreme Court “is not, and has never been, primarily concerned with the correction of errors in lower court decisions.”16 And summary opinions—although capable of making law—are poorly suited to the task, because they are not the products of merits briefing and oral argument.

The best way to understand summary disposition—and, this Essay argues, the way that the Robert Court does understand it—is as a tool to manage and oversee the docket of lower courts. Summary disposition presents concrete advantages for a high court facing a rising tide of petitions from lower courts, as the Supreme Court currently is.17 By issuing GVRs, the Court can ensure that more lower-court decisions take account of intervening precedent without the Court spending its own time and energy on cases that pose similar issues. By issuing summary opinions, the Court can send signals about its commitments and priorities, even on settled areas of law, by illustrating particularly egregious misapplications. In other words, summary disposition allows the Court, acting in its managerial capacity—rather than its lawmaking or its error-correcting capacity—to dispose of more cases with less effort, to correct egregious legal errors when they arise, and to preserve the Court’s limited resources for cases that present novel legal problems.

But it also presents disadvantages. Summary orders that dispose of lower-court judgments without explication—although rare today—result in fewer and less intelligible legal principles for litigants and lower courts to consider. Summary opinions risk significant unfairness to litigants, who have not had the opportunity to submit merits briefing on their cases. Perhaps most disturbingly, summary consideration of all kinds may lead to “erroneous or ill-advised decisions,”18 because the Court, in making its decision, will not have benefited from merits briefing or oral argument. The costs of summary disposition are not insubstantial—especially if used to do more than apply well-established legal principles to new circumstances.

II. Summary Disposition in Practice: A View from the Roberts Court

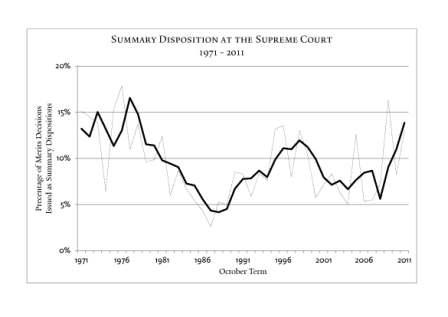

The last few years have witnessed intermittent muttering over the use of summary disposition at the Roberts Court. Professor Vikram Amar has observed that the Court is increasingly willing to use summary disposition to rebuke lower courts, and he has even claimed that the Court has occasionally acted out of “frustration and anger.”19 Veteran Supreme Court litigator Kevin Russell noted “an unusually large number of summary reversals” in one recent term.20 And Adam Liptak, in the New York Times, has called the summary reversal “a favorite tool of the court led by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.”21 Professor Ira Robbins has conducted the most thorough examination of summary disposition at the Roberts Court, surveying the Court’s opinions and noting that, “[i]n the first six years of Chief Justice Roberts’s tenure, almost nine percent of the Court’s full opinions were per curiams.”22

The thrust of those discussions has been the volume of summary dispositions: from Liptak to Russell, commentators have expressed concern that the Roberts Court is more likely than its predecessors to consider and decide cases summarily. The data, however, cast doubt on such speculation. The 2009 Term that alarmed Russell, in which the Court ultimately issued fifteen per curiam reversals of lower courts, was an outlier. In the previous three Terms (2006, 2007, and 2008), the Court issued four, four, and six such reversals, respectively, and in the subsequent Term it issued only seven. More broadly, while the proportion of per curiam dispositions (measured as a percentage of overall merits dispositions) has risen slightly over the first seven Terms of the Roberts Court—from eight percent in its first year to just under fourteen percent23—only in 2009 did it approach the levels it reached during the Burger Court, when it topped sixteen percent.24 The Roberts Court has not summarily disposed of cases on the merits more often than its predecessors did.

Figure 1.29

The Court has, however, summarily disposed of cases in a different way from what its predecessors did. The Warren Court became known for an unusually aggressive approach to summary disposition: in sixteen Terms, the Warren Court issued over 250 decisions reversing lower courts with “no more than a citation or two by way of explanation.”25 Some reversals contained no explanation whatsoever.26 The Burger Court, almost certainly in response to criticism of the Warren Court’s approach to such cases,27 all but eliminated the summary order from the Court’s toolkit and reinstated the Court’s practice of remanding cases to lower courts for consideration.28 The Roberts Court has continued to use the Burger Court’s tools—the GVR and the summary order—but has, acting in its managerial capacity, expanded the use of those tools to cases that the Burger Court would not have considered appropriate vehicles for summary disposition.

A. GVRs: Remanding in Search of Error

First, the Roberts Court has expanded the use of summary reconsideration orders (or GVRs) for cases that once would not have warranted them, because the underlying opinions neither rely on a recently changed legal premise nor present clear error.

The Court has expanded its use of the GVR in absolute terms as well: in its first seven Terms, the Roberts Court remanded, on average, more than 110 cases per Term to the lower courts “in light of”30 an intervening development—almost twice as often as the Burger Court did in the 1975 to 1979 Terms,31 and outnumbering, in most Terms, the number of cases disposed of on the merits. (By contrast, the Burger Court never issued more GVRs than signed opinions, and usually issued fewer than half as many.32) This volume is explained in part by United States v. Booker,33 which held that the Federal Sentencing Guidelines were not binding on federal courts; the 2005, 2006, and 2007 Terms saw the Court hold—and then remand—hundreds of cases in light of Booker and its progeny.34 But even the more recent post-Booker Terms—2008, 2009, and 2010—saw more than sixty GVRs issued each Term, well above the Burger Court’s average.

It is not the frequency of GVRs that has drawn fire from within the Court, however, but the issuance of such orders in cases that once would not have warranted them. Traditionally, GVRs are issued when an intervening Supreme Court case or other precedential ruling renders a legal premise relied upon in the original holding outdated.35 The practice dates in large part to the Burger Court, which reacted to the Warren Court’s practice of reversing cases outright in light of intervening Supreme Court decisions by simply remanding those cases for reconsideration instead.36 The GVR has always been seen as a procedural innovation (it is not described in the Supreme Court Rules), and generally as one with managerial benefits: by using the GVR, the Court could ensure that new rules were broadly applied to pending cases as well as future ones, maximize the impact of those rules while minimizing time on briefing and argument, and preserve its relationship with the lower courts.37

The Roberts Court, though, has used the GVR differently. Rather than remand cases to lower courts in light of intervening precedential rulings, it has remanded cases to lower courts simply to consider arguments or case law that they could have relied on but did not. In Youngblood v. West Virginia,38 the Court remanded a criminal case to the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia, instructing it to address a constitutional issue that it had simply not considered in its opinion. “If this Court is to reach the merits of this case,” the per curiam opinion stated, “it would be better to have the benefit of the views of the [state court] on the Brady issue.”39 Justice Scalia dissented. Noting that there had been no change in the factual or legal context of the case, he castigated the Court for eviscerating the remains of its own GVR doctrine and instead “vacat[ing] and remand[ing] in light of nothing.”40

Since Youngblood, the Roberts Court has continued to expand the use of what Justice Scalia calls the “GVR-in-light-of-nothing.”41 In Nunez v. United States,42 the Court remanded a case to the Seventh Circuit in light of the government’s confession of error—not because the Department of Justice thought that the Seventh Circuit had erroneously ruled in its favor, but because it thought it had correctly ruled in its favor, but for the wrong reason (the Department argued the lower court had misconstrued the defendant’s plea agreement). In Webster v. Cooper,43 the Court remanded a case to the Fifth Circuit in light of a case that preceded that court’s decision by several months (and that presumably the Fifth Circuit had had ample time to consider). And in Wellons v. Hall,44 the Court remanded a case to the Eleventh Circuit in light of an intervening Supreme Court decision that implicated only one of the two independent grounds the lower court had found for affirming a defendant’s conviction. In all three cases, Justice Scalia dissented. Because “we suspect that [the case] may be wrong,” he wrote in Webster, “and do not want to waste our time figuring it out, we instruct the Court of Appeals to do the job again, with a particular issue prominently in mind.”45

This revolution in the Court’s GVR jurisprudence is not exclusively a product of the Roberts Court,46 but the Court under Chief Justice Roberts has continued and expanded it.47 Because these cases do not rely on changed premises but merely (potentially) faulty ones, other Courts might not have considered the GVR an appropriate tool to use. And because they do not, in general, present important questions of federal law or involve clear error (just potential error), other Courts might not have granted review at all, leaving the lower courts’ decisions untouched. The Roberts Court, however, has expanded the use of the GVR, a procedural innovation, to increase its influence over the lower courts, both federal and state. It has, in other words, acted neither in its lawmaking capacity nor—entirely—in its error-correcting capacity, but rather in its managerial capacity. In remanding in search of error, the Roberts Court has signaled a new era of management and oversight within the judicial system.

B. Summary Opinions: Correcting Errors Without Knowing the Facts

Second, the Roberts Court has embraced the use of summary disposition in cases that present contested questions of fact. Such cases are presumably not ripe for the Supreme Court’s discretionary review at all: Rule 10 states that “[a] petition for a writ of certiorari is rarely granted when the asserted error consists of erroneous factual findings or the misapplication of a properly stated rule of law.”48 And although summary disposition is arguably appropriate when used to correct clearly erroneous lower-court decisions, the Court has traditionally denied review to cases that present only perceived errors of fact.49

In the first case of the 2011 Term, Justice Ginsburg argued that this principle militated against plenary review of Cavazos v. Smith.50 In that case, the Court reversed the Ninth Circuit’s grant of federal habeas relief to a California woman accused of assaulting her grandson. Justice Ginsburg dissented. Describing the case as “notably fact-bound,” she argued that the Court should have denied the certiorari petition altogether, pursuant to its traditional practice.51 And even if review had been appropriate, she argued, summary disposition would not have been: “The fact-intensive character of the cases calls for . . . the adversarial presentation that full briefing and argument afford.”52But the Court was unconvinced—perhaps, as Justice Ginsburg noted (in line with Professor Amar’s speculation53), because the majority was intent on “teach[ing] the Ninth Circuit a lesson.”54

The Roberts Court has been aided in its habit of reversing fact-bound cases by a federal statute that seems to envision—and invite—just such intervention: the provision of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA)55 that precludes federal courts from overturning state-court criminal convictions unless the lower court’s decision was contrary to “clearly established Federal law” or the result of an “unreasonable determination of the facts.”56 AEDPA authorizes the Court to overturn defendant-friendly appellate judgments in particularly fact-sensitive cases by establishing a heightened presumption that the state trial court, not the federal appellate court, correctly adjudicated those facts. Indeed, roughly half of the Roberts Court’s summary reversals have issued in criminal cases in which the defendant below had raised a federal habeas claim; in almost all of these cases, the defendant lost at the Court.57

Still, the Supreme Court is hardly required by AEDPA to grant these cases. Indeed, the traditional presumption is that the Court will not grant petitions for writs of certiorari in which appellate courts upend fact-bound trial-court decisions, despite the traditional degree of deference that trial courts’ findings of fact are owed.58 Such cases certainly do not present important questions of federal law, other than the application of AEDPA, and if they present errors, those errors consist only of “the misapplication of a properly stated rule of law.”59 The Roberts Court, however, not only has granted the certiorari petitions in these cases, but has proceeded to summarily adjudicate them. In doing so, as Justice Ginsburg noted in dissent, the Court seems to be treating them as vehicles—“lesson[s]” to the federal judiciary about the Court’s own commitments and priorities.60 One recent study found that AEDPA has reduced the habeas grant rate in noncapital cases to less than one percent.61 Evidently, the courts are listening.62

C. Summary Opinions: Making Law Without Hearing the Arguments

Finally, in some instances the Roberts Court has used summary disposition in cases that present contested questions of law. Although such cases are presumably ripe for Supreme Court review, at least if they present “important question[s] of federal law,”63 they are presumably not appropriate candidates for summary disposition. Indeed, Justices from a variety of ideological backgrounds have agreed that summary disposition is improper when “employed to change or extend the law in significant respects.”64 Because these cases are perhaps most likely to benefit from the “adversarial presentation that full briefing and argument afford,”65 they are well-suited to plenary review.

But the Justices arguing against summary disposition in these cases have done so in dissent. No Court has entirely resisted the temptation to dispose of cases that seem to present questions similar to those the Court has previously considered—and the Roberts Court has continued, if not exacerbated, that trend. For instance, the Court in Presley v. Georgia66 considered whether the Sixth Amendment right to a public trial extended to the voir dire. Seven Justices concluded, in a per curiam opinion, that the question was “well settled” under previous cases that addressed whether the First Amendment guarantees a similar right to the public.67 Justice Thomas, joined by Justice Scalia, dissented on the merits and the method: “Today the Court summarily disposes of two important questions it left unanswered 25 years ago . . . . I respectfully dissent from the Court’s summary disposition of these important questions.”68

Presley is not alone. In Spears v. United States,69 a divided Court summarily reversed the Eighth Circuit’s rejection of the district court’s decision declining to adopt the sentencing ratio set forth in the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for the possession of crack and powder cocaine. And in Wilkins v. Gaddy,70 a unanimous Court overturned not just one Fourth Circuit case, but the fifteen-year line of 42 U.S.C. § 1983 circuit precedent on which it was based, without the benefit of merits briefing or oral argument.71 Cases such as Wilkins perhaps fall into the category of cases described by Justice Marshall in the 1980s, in which “the law is well settled and stable, the facts are not in dispute, and the decision below is clearly in error.”72 But these cases are still troubling, not only because they upset reliance interests (as the Court did in Wilkins), but because they risk “rendering erroneous or ill-advised decisions that may confuse the lower courts.”73

The Roberts Court, which in some instances has embraced the use of procedural tools to manage and oversee the lower courts, has almost certainly not consciously extended summary disposition to cases that present contested questions of law. But cases like Presley, Spears, and Wilkins illustrate one consequence of a court increasingly comfortable acting in its managerial capacity: the risk of carelessness. A Court comfortable with issuing GVRs and summary opinions in cases it might otherwise have declined to review may also be more likely to issue summary opinions where they are simply inappropriate, because they “make new law.”74 This critique is not altogether new; in 1982, Justice Stevens accused the Court of mismanaging its discretionary docket, “encourag[ing]” rather than “resist[ing] . . . the rising administrative tide,” by issuing an “ever-increasing” stream of per curiam opinions.75 But it has surely never seemed more apt than today, when the Court does more than ever to curate the docket of lower courts.

Conclusion

The risk of judicial carelessness is certainly controllable. Justice Marshall once argued that, “when the Court contemplates a summary disposition it should, at the very least, invite the parties to file supplemental briefs on the merits, at their option.”76 Alternatively, a mandatory practice of demanding the full record from lower courts in fact-sensitive cases—which the Court does not always do—would reduce some risk of erroneous adjudication. The Court could adopt a more potent rule similar to the one adopted by the federal appellate courts,77 and simply limit its use of summary disposition to cases in which all Justices, or at least a “supermajority” (e.g., seven of nine), agree that it is warranted.78 This approach might reduce the likelihood that the Court would overturn highly fact-sensitive decisions of lower courts, as in Cavazos; it would almost certainly reduce the likelihood, though, that the Court would actually create new law.

This proposal, in turn, casts new light on American Tradition Partnership, in which summary reversal commanded only the votes of five Justices. What of the case? The case was not fact-bound, like Cavazos, nor—as even the Court's critics would admit—legally contested. But American Tradition Partnership is, all the same, entirely consistent with the Roberts Court’s use of summary disposition. The case provides a perfect example of the Court’s willingness to grant and adjudicate cases that—although they present already-settled questions of federal law—send signals to lower courts about the Court’s own commitments and priorities. The majority, at least, surely saw the case as one in which “the law is settled and stable, the facts are not in dispute, and the decision below is clearly in error.”79 But the dissent certainly saw the law as anything but settled and stable. “Considerable experience . . . since the Court’s decision in Citizens United,” wrote Justice Breyer, “casts grave doubt on the Court’s supposition that independent expenditures do not corrupt or appear to do so.”80

Arguably, it is exactly this—the opportunity for a minority on the Court to demonstrate that the law is less settled than a majority believes—that a supermajority rule would protect. A supermajority rule would probably not have prevented the Court from ultimately overturning the decision of the Montana Supreme Court: Justice Kennedy’s vote did not appear to be in doubt. But it would have continued a conversation over a question that a full third of the Court thought was not yet settled. It would, moreover, have required the Justices in the majority to check their understanding of the law against the best arguments of the bar and the bench to the contrary. The purpose of this Essay is not to argue against summary disposition, for the benefits of a managerial approach are clear. But the risk of error is equally clear—and the benefits of debate, especially in cases important enough to warrant review, are not insignificant. If the Court is to continue to act in its managerial capacity, it should consider how it uses the tools at its disposal.

Alex Hemmer is a member of the Yale Law School J.D. Class of 2014 and an editor of The Yale Law Journal. The author is indebted to Linda Greenhouse for her encouragement and to Bridget Fahey, Lauren Thomas, and the staff of The Yale Law Journal Online for their helpful feedback.

Preferred citation: Alex Hemmer, Courts as Managers: American Tradition Partnership v. Bullock and Summary Disposition at the Roberts Court, 122 Yale L.J. Online 209 (2013), http://yalelawjournal.org/forum/courts-as-managers-american-tradition-partnership-v-bullock-and-summary-disposition-at-the-roberts-court.