Apple and the American Revolution: Remembering Why We Have the fourth Amendment

On February 16, 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) obtained an unprecedented court order in the San Bernardino shooting case that would have forced Apple to design and deliver to the DOJ software capable of destroying the encryption and passcode protections built into the iPhone.1 The DOJ asserted that this order was simply the extension of a warrant obtained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to search the shooter’s iPhone, which had been locked with a standard passcode.

The FBI’s litigation strategy backfired when Apple decided to commit its resources to getting the order vacated. The Fourth Amendment’s guarantee that “[t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated”2 was technically not at issue in the San Bernardino case. Nonetheless, when Apple CEO Tim Cook said, “we fear that this demand would undermine the very freedoms and liberty our government is meant to protect,”3Americans began to feel—perhaps for the first time since the Revolutionary Era—that they needed protection against search warrants.

Apple assembled a team of legal luminaries to challenge the San Bernardino order, including former Solicitor General Ted Olson, who told the media that a loss for Apple would “lead to a police state.”4 The day before the highly anticipated hearing, the DOJ unexpectedly requested an adjournment;5 a week later, the DOJ asked that the order be vacated as no longer necessary, saying that an unnamed “third party” had broken the passcode for the FBI.6 The DOJ similarly backed off in a later case in New York.7

What happened? The FBI took a beating in the media, public opinion, and Congress. As the story of FBI v. Apple received tremendous national media coverage,8 public opinion shifted to support Apple’s position.9 In a headline, the editorial board of the New York Times opined, “Apple Is Right to Challenge an Order to Help the FBI”;10 the Wall Street Journal said in an editorial that “more secure phones are a major advance for human freedom”;11 and Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Clarence Page concluded that the “future of . . . personal liberties[] is at stake.”12

The clash between Apple and the FBI/DOJ quickly made its way to Congress’s doorstep. Within days of the San Bernardino order, congressional committees commenced hearings in which FBI Director James Comey came under considerable criticism.13 Two Senators proposed legislation that would force companies to comply with court decryption orders, but the idea drew a filibuster threat, failed to gain support (even from the White House), and was never introduced.14 The House Homeland Security Committee dismissed the idea of a statute that would authorize “law enforcement access to obtain encrypted data with a court order” as “riddled with unintended consequences,” and concluded that “the best way for Congress and the nation to proceed at this juncture is to formally convene a commission of experts to thoughtfully examine not just the matter of encryption and law enforcement, but law enforcement’s duty in a world of rapidly evolving digital technology.”15 Two weeks after the court in San Bernardino issued its order, representatives introduced bipartisan legislation to create a congressionally led expert commission,16 and in March the House Judiciary Committee and the House Energy and Commerce Committee jointly established a Bipartisan Encryption Working Group.17

Two recent lawsuits filed by Microsoft against the DOJ have only increased the need for further legislative action.18 On April 14, 2016, Microsoft sued the DOJ, alleging that its pervasive use of the “delayed notice” provisions in 18 U.S.C. §2705 violated the Fourth Amendment by preventing Microsoft from notifying its customers when it was served with search warrants for emails stored “in the cloud” on Microsoft servers.19 In July, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ordered that Microsoft’s motion to quash such a search warrant in a different case be granted because the statute used by the DOJ did not authorize warrants for emails stored outside the United States.20

This recent use of high-profile litigation to challenge the power of search warrants strikingly parallels a series of lawsuits from the 1760s. One such case was a petition brought by citizens of Boston asking the Superior Court to stop issuing “writs of assistance” that authorized forcible entry into their homes to search any “Vaults, Cellars . . . or other Places” and to open “any Trunks, Chests, Boxes, fardells or Packs” where smuggled goods or merchandise were “suspected . . . to be concealed.”21 This case and the ensuing controversy over writs of assistance were among the critical events leading to the American Revolution.22 A second series of cases, filed in England, successfully challenged the use of warrants to arrest suspected authors and publishers of political pamphlets and to seize all their personal papers. These warrants were condemned as “general warrants” because they authorized nationwide general searches and were not limited to specifically identified persons, places, and papers.

This Essay will examine the writs of assistance and general warrants cases of the 1760s to show how they helped establish the following bedrock principles underlying the Fourth Amendment:

The right to keep private papers secure from government surveillance is essential to liberty.23

Search warrants are a grave threat to the security of private papers.24

General warrants to seize and search all of a person’s private papers must be prohibited.25

After reviewing this history, this Essay will show how the DOJ’s current practices in using search warrants for electronically stored information (ESI) violate these fundamental principles. This Essay concludes by proposing new legislation to restore Fourth Amendment protections to our “private papers” now kept in digital form.

I. why we have the fourth amendment

No less an authority than John Adams26 has told us “the child Independence was born” in 176127 when James Otis filed a petition pro bono on behalf of a group of Boston citizens opposing reissuance of writs of assistance.28 According to Adams’s eyewitness account, Otis told the court that the writ of assistance was “the worst instrument of arbitrary power, the most destructive of English liberty,”29 after which “[e]very man of an [immense] crowded Audience appeared to me to go away, as I did, ready to take up Arms against Writts of Assistants [sic]. Then and there was the first scene of the first Act of Opposition to the arbitrary Claims of Great Britain.”30

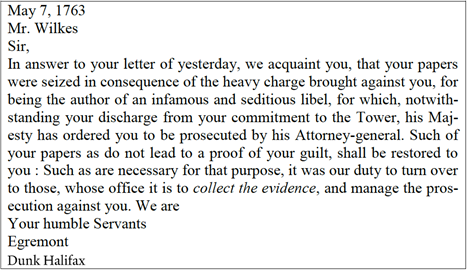

Just two years after Otis’s passionate speech, a group of political pamphleteers in England struck back against royal oppression by filing a number of successful damage actions challenging the use of general warrants to seize and search their private papers.31 In the most famous of these cases, the British Secretary of State, Lord Halifax, had issued a general warrant “to make strict and diligent search for the...authors, printers and publishers of a seditious and treasonable paper, [e]ntitled The North Briton, No. 45...and...any of them having found, to apprehend and seize [them], together with their papers.”32 The dragnet search led to the arrest of John Wilkes, a member of Parliament, for being the suspected author. When officers searched Wilkes’s London home and encountered a table with locked drawers, they asked instructions of Lord Halifax, who replied that the drawers must be opened and all manuscripts seized.33 After summoning a locksmith, the officers took “all the papers in those drawers and a pocket-book of Mr. Wilkes’s,” put them in a sack, and carried them away.34

Chief Justice Charles Pratt told the Wilkes jury that the defendant’s claim to be acting under a legal warrant “was a point of the greatest consequence he had ever met with in his whole practice.”35 He went on, “If such a power is truly invested in a Secretary of State . . . it . . . is totally subversive of . . . liberty . . . .”36

In another pamphleteer lawsuit, the plaintiff’s lawyer told the jury:

[R]ansacking a man’s secret drawers and boxes to come at evidence against him[] is like racking his body to come at his secret thoughts.... [H]as a Secretary of State a right to see all a man’s private letters of correspondence, family concerns, trade and business? [T]his would be monstrous indeed; and if it were lawful, no man could endure to live in this country.”37

Affirming the jury’s verdict on appeal two years later, Chief Justice Pratt (recently given the title Lord Camden) authored one of the most widely cited judicial decisions in Fourth Amendment jurisprudence:38 he declared that “[p]apers are . . . [our] dearest property; and are so far from enduring a seizure, that they will hardly bear an inspection”39 and concluded that “I can safely answer, there is no[]” “written law that gives any magistrate” the power to search and seize personal papers.40

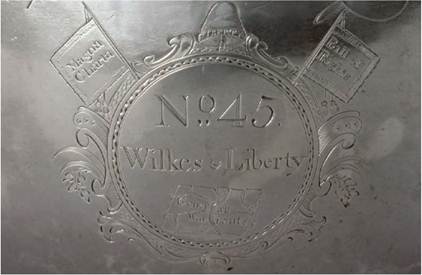

Colonists understood that resistance to writs of assistance in Boston and opposition in England to the use of general warrants to search private papers were all part of a unified struggle for liberty.41 The famous silver bowl designed in 1768 by Paul Revere for the Boston Sons of Liberty says it all: the image of a general warrant torn in half is paired with the words “No. 45” and “Wilkes & Liberty” and topped by flags labeled “Magna Carta” and “Bill of Rights.”42

|

After Independence, many revolutionaries raised the concern that a federal government would, like the vanquished British, abuse the power of the search warrant. At the Virginia ratifying convention for the proposed Constitution, Patrick Henry declared: “unless the general government be restrained by a bill of rights . . . [it may] go into your cellars and rooms and search, ransack and measure every thing you eat, drink and wear. Everything the most sacred may be searched and ransacked by the strong hand of power.”49 Ultimately both Virginia and New York conditioned approval on adoption of a bill of rights that included a search warrant provision that incorporated key points from the 1761 Otis argument and closely modeled John Adams’s work on the Massachusetts Constitution.50

This history makes clear that the text of the Fourth Amendment was addressed to the kinds of search warrants that were opposed in the writs of assistance and general warrants litigation. In particular, as we now turn to the DOJ’s use of search warrants for email stored in a cloud or on cell phones, we should keep in mind the facts of the Wilkes case, described as “the paradigm search and seizure case for Americans”51 in the eighteenth century, and especially the image of royal officers breaking open a locked cabinet, gathering all the papers they can find, and carrying them off for later review.

II. unconstitutional search warrant practices

The FBI’s efforts to break iPhone encryption are only the latest chapter in a very troubling story. Instead of recognizing the Fourth Amendment’s special protections for private papers, the DOJ is re-enacting the procedures used by Lord Halifax and applying them to seizing and searching electronically stored information, whether maintained on a conventional computer, in a cloud, or on a cell phone. The DOJ standard operating procedure is to obtain warrants that authorize copying the entire database. Although the DOJ may then choose to use keyword searches and other techniques to look for items of information for which it actually has probable cause to search, it writes into the warrant discretion to look at everything if it so chooses.52

In 2009, a new section was added to Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41 (Search and Seizure) on “Warrant[s] Seeking Electronically Stored Information.” The new provisions codified the already prevailing DOJ practice of requesting ESI warrants that authorized a “two-step process”: (1) seizing either an entire computer hard drive or creating a mirror “image” of the drive, followed by (2) “later review,” typically by an expert in computer forensics, “to determine what [ESI on the drive] falls within the scope of the warrant.”53 Codification of the two-step process coincided with the rise of web-based email service, and the DOJ quickly adapted this procedure, designed for computer hardware, to obtain mirror images of entire email accounts stored in the cloud. The warrant quashed by the Second Circuit last July is illustrative. It ordered Microsoft to turn over “for the period of the inception of the account to the present: (a) [t]he contents of all emails stored in the account...[and] (b) [a]ll records or other information...including address books, contact and buddy lists, pictures, and files....”54 The warrant further stated: “A variety of techniques may be employed to search the seized emails for evidence of the specified crimes including...email-by-email review.”55

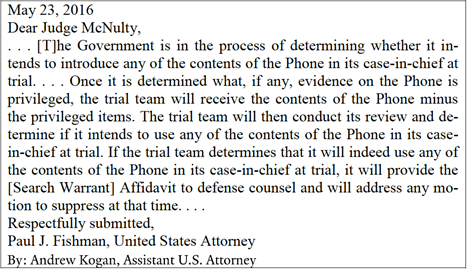

The DOJ has now brought the two-step process to cell phone searches, the troubling consequences of which are on display in United States v. Ravelo. In this prosecution for alleged white-collar crime the government downloaded all “the user-generated content” from the iPhone of a prominent attorney including “emails, text messages, contact list, and user-generated photographs,”56 totaling approximately 90,000 separate items.57 The U.S. Attorney wrote a letter remarkably similar to the letter Lord Halifax sent to Wilkes centuries ago:

figure 1.58

letter from lord halifax to mr. wilkes

figure 2.59

letter from mr. kogan to judge mcnulty

|

U.S. Attorney Fishman has further taken the position that, even if the court grants pending motions to suppress all evidence from the phone and return the phone to Ravelo, thus ruling that the cell phone was seized and searched in violation of the Fourth Amendment, “the government w[ill] likely retain copies of the contents of the Phone” and may still use that digital data against Ravelo in a variety of ways.60

It has not escaped judicial notice that warrants authorizing the two-step procedure risk becoming general warrants prohibited by the Fourth Amendment, but to date the DOJ has resisted court attempts to address the problem.61 The DOJ has defended step one by saying that effective computer forensics require access to the complete database, and has refused to limit the second step of review of the database,62 thus enabling the kind of “email by email” review that is authorized by the Microsoft warrant63 and that the Ravelo prosecutors intend to use.64

The DOJ also enjoys a tremendous strategic advantage due to the lack of due process in most ESI searches. Search warrant applications are approved ex parte, based entirely on the government’s one-sided presentation, with neither notice to the person affected nor the opportunity to be heard.65 Reliable estimates indicate that thousands of ESI search warrants are kept secret every year through orders to seal the file from both the public and the person affected.66The government can appeal the magistrate’s decision to deny a warrant application, but the person affected has no right to judicial review before the warrant is executed.67 As argued in the current Microsoft suit challenging DOJ-requested gag orders,68 the lack of due process is even worse when the warrant is directed at remotely stored email. The only way Americans affected by such gag orders will ever learn that the government has been able to read all of their emails is if the government decides to prosecute them and attempts to use what it has obtained to secure a conviction.

III. congressional action is needed

The bipartisan congressional initiatives described in the introduction are encouraging because Congress is the best forum for developing a comprehensive approach to ESI searches that honors the history and text of the Fourth Amendment.

In the Revolutionary Era, warrants to search private papers were consistently compared to extracting confessions by torture.69 We ought to take seriously the argument that, just as torture is always unlawful (even when national security may be at stake), Congress should categorically prohibit both federal and state governments from using warrants to obtain personal correspondence and other private information protected by user-controlled encryption that is stored on cell phones or in the cloud.

At a minimum, warrants to seize and search ESI stored on personal cell phones and computers or in personal cloud accounts should be issued only for compelling reasons and should be vigilantly regulated to ensure compliance with the Fourth Amendment’s particularity requirement. Such a regulation might include the following provisions, the first five of which track federal law regulating wiretapping and electronic surveillance:

(1)Felony to obtain, disclose, or use ESI except as authorized by this statute;70

(2)Limited to specified serious crimes;71

(3)Limited to circumstances where other investigatory procedures have already been tried or are unavailable;72

(4)Must be authorized by a DOJ official at least at the level of Deputy Assistant Attorney General or, for state warrants, the Attorney General of the relevant jurisdiction;73 and

(5)Annual detailed report to Congress on ESI warrants.74

(6)If a warrant authorizes seizure of a device containing ESI or the copying of ESI from such a device or any other storage media (such as a remote server), the device or copied ESI shall be held under court supervision until the owner of the ESI has been provided notice and an opportunity for a hearing to contest the terms of the warrant and/or the procedures to be used to search the device or copied ESI for one or more items of information described with particularity in the warrant.75

The final proposal recognizes that the risk of tampering with or destroying the potential evidence identified in the warrant is minimized by seizure of the device or copying of the ESI. The target of the warrant is therefore entitled to similar rights to notice and a hearing as if his ESI had been sought by grand jury subpoena.76 The other provisions of the sixth proposal are inspired by recommendations made by five federal appellate judges in 201077 and subsequently incorporated into computer search warrant procedures approved by the Vermont Supreme Court in 2012.78

There have been warnings from an increasing number of federal judges about the DOJ’s disregard for the particularity requirement of the Fourth Amendment in its use of ESI search warrants.79 Scholars, including two former federal prosecutors with specialized knowledge about ESI search procedures, have also voiced concerns.80 Over twenty years ago Akhil Amar claimed that a view of the Fourth Amendment as just a tool of criminal procedure, primarily protecting “criminals getting off on...technicalities,” risked making the Amendment “contemptible in the eyes of judges and citizens.”81 Amar’s call for a “return to first principles” by reading carefully the words of the Fourth Amendment and the history that gave rise to those words82 fell largely on deaf ears. But in the last nine months, two of the three most valuable companies in America83 have taken the offensive against the federal government to assert the Fourth Amendment rights of everyone. This offensive has the potential to reinvigorate the nation’s commitment to the Fourth Amendment, generating momentum for a much-needed and long-overdue reassessment of the use of warrants to seize and search electronically stored information, whether stored in cell phones or conventional computers, or in the cloud.

Clark D. Cunningham is the W. Lee Burge Chair in Law & Ethics at Georgia State University College of Law in Atlanta. Thanks to Ryan Bozarth, Tosha Dunn, and reference librarians Pamela C. Brannon, Margaret Elizabeth Butler, and Jonathan Edward Germann for research assistance. The thinking that underlies this essay owes much to teaching and guidance received from James Boyd White and the late Joseph Grano. Cited case materials and other information are available at: http://clarkcunningham.org/Apple/ [https://perma.cc/7JPZ-BMXU].

Preferred Citation: Clark D. Cunningham, Apple and the American Revolution: Remembering Why We Have the Fourth Amendment, 126 Yale L.J. F. 216 (2016) http://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/ apple-and-the-american-revolution.

Tim Cook, A Message to Our Customers, Apple (Feb. 16, 2016), http://http://www.apple.com/customer-letter [http://perma.cc/8EU6-49JK].

David Goldman & Laurie Segall, Apple’s Lawyer: If We Lose, It Will Lead to a ‘Police State’, CNNMoney (Feb. 26, 2016, 12:56 PM), http://money.cnn.com/2016/02/26/technology/ted-olson-apple [http://perma.cc/U3YQ-S6S3].

See Government’s Ex Parte Application for a Continuance, In re Search of an Apple iPhone, (C.D. Cal. Mar. 21, 2016), http://www.scribd.com/doc/305549490/Apple-vs-FBI-Motion-to-Vacate [http://perma.cc/XKB2-KHEA].

See Government’s Status Report, In re Search of an Apple iPhone, No. 5:16-CM-00010 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 28, 2016), http://www.plainsite.org/dockets/2xdz3nkmq/california-central-district-court/usa-v-in-the-matter-of-the-search-of-an-apple-iphone-seized-during-the-execution-of-a-search-war/ [http://perma.cc/7QBJ-P5KZ].

See, e.g., The Apple-F.B.I. Case, N.Y. Times, http://www.nytimes.com/news-event/apple-fbi-case [http://perma.cc/NT22-JXGC] (indexing more than thirty New York Times articles, including four that appeared on the front page); The Apple-FBI Debate over Encryption, Nat’l Pub. Radio, http://www.npr.org/series/469827708/the-apple-fbi-debate-over-encryption [http://perma.cc/29BC-MZSC] (indexing more than fifty National Public Radio stories); Lev Grossman, Inside Apple CEO Tim Cook’s Fight with the FBI, Time (Mar. 17, 2016), http://time.com/magazine/us/4262476/march-28th-2016-vol-187-no-11-u-s [http://perma.cc/YCC9-FXJS] (covering the controversy on Time’s front cover).

See, e.g., Michael D. Shear, David E. Sanger & Katie Benner, In the Apple Case, a Debate Over Data Hits Home, N.Y. Times (Mar. 13, 2016), http://http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/14/technology/in-the-apple-case-a-debate-over-data-hits-home.html [http://perma.cc/8WLQ-8HW3] (describing the “enormous” pushback against the government’s position).

Editorial, Why Apple Is Right To Challenge an Order To Help the F.B.I., N.Y. Times (Feb. 18, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/19/opinion/why-apple-is-right-to-challenge-an-order-to-help-the-fbi.html [http://perma.cc/X3ST-UWY8].

Editorial, The FBI vs. Apple: The White House Should Have Avoided This Legal and Security Showdown, Wall St. J. (Feb. 19, 2016, 10:17 AM), http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-fbi-vs-apple-1455840721 [http://perma.cc/884M-36JH].

Clarence Page, Apple’s Standoff with FBI Is About More than One iPhone, Chi. Trib.: Page’s Page (Feb. 26, 2016, 1:05 PM), http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/opinion/page/ct-apple-fbi-marco-rubio-iphone-page-perspec-0228-20160226-story.html [http://perma.cc/VR57-WN5G].

See, e.g., Hearing Before the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 114th Cong. (2016) (questions to FBI Director James Comey by Rep. Bob Goodlatte, Chairman, H. Comm. on the Judiciary; Rep. John Conyers, Rep. Jerrold Nadler, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Rep. Ted Poe & Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, Members, H. Comm. on the Judiciary), 2016 WestLaw NewsRoom 6586673; Interview by Scott Simon with Rep. Ted Lieu, After Apple Case, Encryption vs. National Security Dilemma Has Just Begun, Nat’l Pub. Radio (Apr. 2 2016, 8:06 AM), http://http://www.npr.org/2016/04/02/472784761/after-apple-case-encryption-vs-national-security-dilemma-has-just-begun [http://perma.cc/ZK57-UWXR] (“[T]here has been not a single case that the FBI or anybody else can come up with that would have showed that had the FBI had a back door to a smartphone that they could have stopped any terrorist attack anywhere. What the FBI really is trying to do is to make some law enforcement investigations easier so they can prosecute criminals. It is not a terrorism issue. It really is a law enforcement investigatory tool issue. And the question is - do you want to make some law enforcement investigations easier, but damage national security in the process?”); Cecilia Kang, Ron Wyden Discusses Encryption, Data Privacy and Security, N.Y. Times (Oct. 9, 2016), http://http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/10/technology/ron-wyden-discusses-encryption-data-privacy-and-security.html [http://perma.cc/NGV6-UM4D].

Mark Hosenball & Dustin Volz, Exclusive: White House Declines To Support Encryption Legislation – Sources, Reuters (Apr. 7, 2016, 6:27 AM), http://www.reuters.com/article/us-apple-encryption-legislation-idUSKCN0X32M4 [http://perma.cc/NDV4-KR4R]; Dustin Volz, Mark Hosenball & Joseph Menn, Push for Encryption Law Falters Despite Apple Case Spotlight, Reuters, (May 27, 2016, 6:00AM), http://www.reuters.com/article/usa -encryption-legislation-idUSL2N18N20G, [http://perma.cc/C72K-95UM]; Danny Yadron, Oregon Senator Threatens To Filibuster Any Attempt To Weaken Encryption, Guardian (Mar. 30, 2016, 10:04 PM), http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/mar/30/oregon-senator -ron-wyden-filibuster-encryption-rightscon [http://perma.cc/3RFE-DMV5].

Majority Staff of H. Homeland Sec. Comm., 114th Cong., Going Dark, Going Forward: A Primer on the Encryption Debate 3 (2016), http://homeland.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Staff-Report-Going-Dark-Going-Forward.pdf [http://perma.cc/WZ7P-ZFX8].

Digital Security Commission Act of 2016, H.R. 4651, 114th Cong. (introduced Feb. 29, 2016); see also McCaul-Warner Commission on Digital Security, H. Homeland Sec. Comm., http://homeland.house.gov/mccaul-warner-commission-2/ [http://perma.cc/DY63 -6DEN].

Press Release, H. Energy & Commerce Comm., Upton, Pallone, Goodlatte, Conyers Announce Bipartisan Encryption Working Group (Mar. 21, 2016), http://energycommerce.house.gov/news-center/press-releases/upton-pallone-goodlatte-conyers-announce -bipartisan-encryption-working [http://perma.cc/ZXA5-C4UQ]; Press Release, H. Energy & Commerce Comm., Congressional Leaders: Bipartisan Encryption Working Group Making Progress (June 22, 2016), http://energycommerce.house.gov/news-center/press -releases/congressional-leaders-bipartisan-encryption-working-group-making-progress [http://perma.cc/CQT5-B7MT].

See, e.g., Press Release, Office of Senator Orin Hatch, Hatch Urges DOJ to Work with Congress on ICPA (Oct. 13, 2016), http://www.hatch.senate.gov/public/index.cfm /2016/10/hatch-urges-doj-to-work-with-congress-on-icpa [https://perma.cc/E53Q-X2KE] (urging the Department of Justice to work with Congress on new legislation to respond to the Second Circuit’s decision in Microsoft).

See text accompanying notes 26-30, infra; Oliver M. Dickerson, Writs of Assistance as a Cause of the Revolution, in The Era of the American Revolution 40 (Richard B. Morris ed., 1939); Tracey Maclin, When the Cure for the Fourth Amendment is Worse than the Disease, 68 S. Cal. L. Rev. 1, 13-25 (1994).

U.S. Const., amend. IV (“The right of the people to be secure in their . . . papers . . . against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause . . . and particularly describing the . . . things to be seized.”); In the Matter of the Search of Premises Known as: Three Hotmail Email Accounts, No. 16-MJ-8036-DJW, 2016 WL 1239916 (D. Kan. March 28, 2016), at *3-15 (explaining that the purpose of Fourth Amendment’s “particularly describing” requirement is to prevent issuance of general warrants).

William J. Cuddihy, The Fourth Amendment: Origins and Original Meaning 443 (2009) (“The warrant against The North Briton Forty-Five was among the most potent stimulants to adjudication in British legal history . . . . [T]he warrant figured directly in at least thirty suits or trials. Derivative trials numbered sixteen or more.”); Robert R. Rea, The General Warrant in the Courts of Law: The Cases Arising from North Briton No. 45, in The English Press in Politics 1760-1774, at 59-69 (1963).

Entick v. Carrington (1765) 95 Eng. Rep. 807, 812; 2 Wils. K.B. 275, 282. For a larger excerpt of the Entick decision, see 19 T. B. Howell, A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanors: From the Earliest Period to the Year 1783: 1753-70, at 1030 (1816).

See, e.g., Boyd v. United States, 116 U.S. 616, 626-27 (1886). (“As every American statesman, during our revolutionary and formative period as a nation, was undoubtedly familiar with this monument of English freedom [Lord Camden’s opinion in Entick], . . . it may be confidently asserted that its propositions were in the minds of those who framed the fourth amendment to the constitution, and were considered sufficiently explanatory of what was meant by unreasonable searches and seizures.”).

Paul Revere, Sons of Liberty Bowl, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/sons-of-liberty-bowl-39072 [http://perma.cc/NVK4-YQG5].

Adams’ Minutes of the Argument at Suffolk Superior Court, Boston, on Feb. 24, 1761, in 2 Legal Papers of John Adams, supra note 27, at 142 (“Now one of the most essential branches of English liberty, is the freedom of one’s house . . . . This writ, if it should be declared legal, would totally annihilate this privilege.”).

Comput. Crime & Intellectual Prop. Section, Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations, U.S. Dep’t Just. 79-83 (3d ed. 2009), http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/criminal-ccips/legacy/2015/01/14/ssmanual2009.pdf [http://perma.cc/NEX5-P75T] (“Do Not Place Limitations on the Forensic Techniques That May Be Used to Search”).

Letter from Andrew Kogan, Assistant U.S. Attorney, U.S. Dep’t Justice, to Kevin McNulty, Judge, Dist. N.J. (July 12, 2016), United States v Ravelo (D.N.J. indicted Nov. 5, 2015), (2:15-cr-00576-KM) (no. 90); see historical evidence to the contrary from the writs of assistance and general warrants cases, note 76, infra.

Stephen Wm. Smith, Gagged, Sealed & Delivered: Reforming ECPA’s Secret Docket, 6 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 313, 313 (2012) (describing the search warrant docket of federal magistrates as “the most secret docket in America” and presenting analysis indicating that more than 30,000 federal search warrants issued nationwide in 2006 pursuant to the Electronic Communications Privacy Act were entered subject to an order to seal and that the annual numbers have likely increased since then).

First Amended Complaint for Declaratory Judgment at para. 37, Microsoft Corp. v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, No. 2:16-cv-00538-JLR (W.D. Wash. June 17, 2016), 2016 WL 3381727. As to the government’s argument that the Fourth Amendment does not require notice to the target of the search, see Reply Supporting Motion to Dismiss Pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P.12(B)(1) and 12(B)(6), at 11-13, Microsoft Corp. v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, No. 2:16-cv-00538JLR (W.D. Wash. Sep. 23, 2016).

Cf. 18 U.S.C. § 2511(1), (4) (2012) (stating that, except as otherwise provided in the statute, any person who (a) intentionally intercepts any wire, oral, or electronic communication or (b) intentionally discloses the contents of such interception shall be fined and/or imprisoned not more than five years); id. § 2515 (“Whenever any wire or oral communication has been intercepted, no part of the contents of such communication and no evidence derived therefrom may be received in evidence in any trial, hearing, or other proceeding . . . .”).

Cf. id. at § 2516(1)(a)-(t) (stating that the Attorney General may authorize an application for judicially-approved interceptions when such interception may provide evidence relating to particular serious offenses enumerated in the statute, such as those punishable by death or imprisonment for more than one year).

Cf. id. at § 2516(1) (listing DOJ officials at or above the level of acting Deputy Assistant Attorney General as having the authority to authorize a wiretap application); id. § 2516(2) (explaining that the principal prosecuting attorney of any State or the principal prosecuting attorney of any political subdivision thereof may apply for a wiretap order if authorized by state statute).

Cf. id. at § 2519 (requiring each judge who issues a wiretap order to file a report with the Administrative Office of United States Courts (AOC), each state prosecutor who applies for a wiretap order to issue a similar report to the AOC, and the AOC itself to submit an annual report to Congress documenting the reports it has received); see, e.g., Wiretap Report 2015, U.S. Cts. (Dec. 31, 2015), http://www.uscourts.gov/statistics-reports/wiretap-report-2015 [http://perma.cc/6MB6-MBU2].

This notice and hearing requirement could be deferred in exigent circumstances, such as probable cause that a terrorist attack was imminent. Cf. 18 U.S.C. § 2702(b)(8) (explaining that a provider of electronic communication service may disclose the contents of communication to a governmental entity without a warrant or court order if “the provider, in good faith, believes that an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to any person requires disclosure without delay of communications relating to the emergency”).

See, e.g., United States v. Kitzhaber (In re Grand Jury Subpoena, JK-15-029), 828 F.3d 1083, 1088 n.1 (9th Cir. 2016) (quashing grand jury’s subpoena of defendant’s email as overbroad and in violation of the Fourth Amendment and further describing a subpoena’s recipient’s ability to move to quash a subpoena before any search takes place as sufficiently protective of Fourth Amendment rights (citing City of Los Angeles, Cal v. Patel, 135 S. Ct. 2443, 2453 (2015)). In condemning a Lord Halifax general warrant, Lord Camden said: “It is executed against the party, before he is heard . . . ; . . . [i]t is executed by messengers . . . in the presence or absence of the party, as the messengers shall think fit . . . ..[P]roper checks . . . would require [the messenger] to take an exact inventory, and deliver a copy . . . . [T]he want of [these precautions] is an undeniable argument against the legality of the thing.” Howell, supra note 37, at 1064-65, 1067. Likewise, Otis railed against the writ of assistance because “there’s no return, a man [the executing officer] is accountable to no person for his doings [as would be the case if an inventory was taken and returned with the warrant to the court]. Adams, Adams’ Minutes of the Argument at Suffolk Superior Court, Boston, on Feb. 24, 1761, supra note 27, at 142, 143. See also Wilkes v. Wood (1763) 98 Eng. Rep. 489, 498 (KB) (“no inventory is made”).

See, e.g, United States v. Ganias, 824 F.3d 199, 226 (2d Cir. 2016) (Chin, J. dissenting); In the Matter of the Search of Premises Known as: Three Hotmail Email Accounts, No. 16-MJ-8036-DJW, 2016 WL 1239916 (D. Kan. March 28, 2016), at *50; In re Search of Apple iPhone, 31 F. Supp. 3d 159, 164-65 (D.D.C. 2014); Comprehensive Drug Testing, 621 F.3d at 1178-80.

Paul Ohm, who led a task force in the DOJ Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section, described ESI search warrants as “the closest things to general warrants we have confronted in the history of the Republic,” saying in almost every computer search there is a “manifest lack of probable cause and particularity.” Massive Hard Drives, General Warrants, and the Power of Magistrate Judges, 97 Va. L. Rev. In Brief 1, 4, 11 (2011). Orin Kerr, who wrote the first edition of the DOJ manual on searching computers, Orin S. Kerr, Searches and Seizures in a Digital World, 119 Harvard L. Rev. 531, 574 n.189 (2005), has also concluded that ESI searches conducted by the DOJ seem “perilously like the regime of general warrants that the Fourth Amendment was enacted to stop. Everything can be seized. Everything can be searched.” Orin S. Kerr, Executing Warrants for Digital Evidence: The Case for Use Restrictions on Nonresponsive Data, 48 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 1, 11 (2015).

Stephen Gandel, These Are the 10 Most Valuable Companies in the Fortune 500, Fortune (Feb. 4, 2016), http://fortune.com/2016/02/04/most-valuable-companies-fortune-500-apple [http://perma.cc/KU6S-PXQ8] (noting that Apple is ranked number one, and Microsoft is ranked number three).