Judicial Gobbledygook: The Readability of Supreme Court Writing

Introduction

Writing is the conduit through which courts engage with the public.1 As such, the quality of judicial writing is an important element of the legal system—it determines the clarity of the rules that we live by. Yet, on an empirical level, we know relatively little about it. A court watcher’s gut reaction might be that judicial writing suffers from excess complexity. Indeed, the Federal Judicial Center finds it necessary to encourage judges to avoid wordiness, pomposity, and overly complex phrasing.2 However, we do not know how well judges heed this advice, or whether the quality of judicial writing has changed over time.

This Essay sheds new light on this empirical darkness. It analyzes the readability of over six thousand Supreme Court opinions by measuring the length of sentences and the use of long, polysyllabic words. The data shows that legal writing at the Court has become more complex and difficult to read in recent decades. On an individual level, writing style tends to become somewhat more complex the more years a Justice spends on the court. We also see substantial variation among opinion writers—with Justices Scalia and Sotomayor penning particularly wordy opinions—and a tendency for conservative opinions to be somewhat more difficult to read than their liberal peers.

I. methodology

In order to measure Supreme Court writing styles, I first downloaded all Supreme Court decisions issued since 1946 that are available on CourtListener.com.3 This results in a dataset containing the full text of 6,206 Supreme Court opinions.

There are many ways to determine how easy it is to read a text. Because of its accuracy and reliability, the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG)4 is considered an “exacting” method to do so.5 Like many readability indices, SMOG looks to the length of sentences and the number of long multisyllabic words in each. It produces a measurement that can be roughly interpreted as the number of years of education one would need in order to understand the text. A SMOG score of 12 corresponds to a high school graduate reading level while a text with a SMOG score of 16 would be more appropriate for a college graduate.6

To measure the SMOG scores for the cases within the Supreme Court opinion dataset, I wrote a program that parses the text into sentences, measures the number of syllables in each word, and calculates SMOG values.7 In addition to measuring SMOG, I also noted the year of publication for each opinion, which Justice authored it, how long into his or her tenure the Justice wrote it, and the ideological leanings of the authoring Justice.

II. findings

There are many ways to examine the readability of Supreme Court Justices’ writing styles. In Section II.A, we explore whether the Court’s writing has become more or less clear over time. Subsequently, we look to the relationship between the length of a Justice’s tenure on the court and their writing style and the individual Justice’s trends over the course of their careers. Finally, this Essay briefly explores the relationship between judicial ideology and writing style.

A. Readability over Time

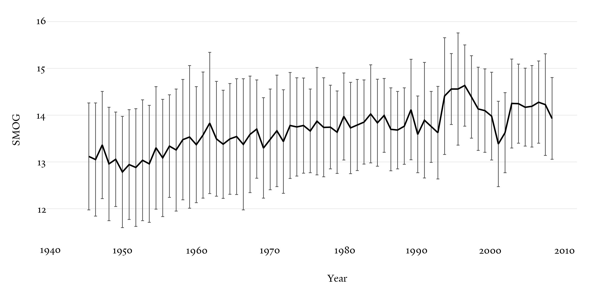

Is it easier to read an opinion drafted today than one drafted decades ago? To answer this question, we can examine the overall SMOG score trend over time, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

readability over time

While the Court’s opinions exhibit a wide range of SMOG scores every year (the graphed line plots the mean SMOG values while the bars extending above and below the line span one standard deviation8 each) there also appears to be a clear upwards trend. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient—which measures the linear dependence (or correlation) between two variables—for year and SMOG is 0.29 (p < 0.0001), suggesting that SMOG scores are indeed increasing over time.9

These historical changes in SMOG align with similar observations by Ryan Black and James Spriggs about changes in opinion length.10 Black and Spriggs identify two changes in the drafting of Supreme Court opinions in the second half of the twentieth century, which contributed to increasing opinion lengths: first, clerks played an increased role in the drafting process,11 and second, electronic typewriters and subsequently computers and word-processing software were introduced.12

These same factors may explain the increasing SMOG results. More clerk participation might increase language complexity, as more authors write, edit, and re-write language in successive stages. This can lead to many authors contributing their voices, bloating the opinion. The introduction of word processors offers an even more straightforward explanation for increasing SMOG scores. SMOG is a function of polysyllabic word use.13 Word processors allow editorial flexibility, encouraging authors to draft and redraft sentences, to add words and clauses to successive drafts, and perhaps replace simple words with longer ones. This type of writing process would lead directly to higher SMOG scores.

The increasing commonality of dissenting opinions offers another potential explanation as to why we have seen rising SMOG in recent decades. Written dissents became much more common in the latter half of the twentieth century.14 By breaking out the SMOG data by vote count and comparing unanimous decisions with those that had dissenting votes, we see that the writing in nonunanimous opinions is marginally more difficult to read than that in unanimous opinions.15 It is possible that writing becomes more complicated when Justices are forced to deal not only with the facts and legal issues implicated by a case, but also the dissenting opinions of their peers. Alternately, it could be that these opinions represent more complex and controversial legal issues and that this complexity is reflected in the written opinions.

B. Readability and Tenure on the Court

One might suspect that a Justice’s writing style changes over the course of his or her tenure. Junior Justices may systematically be assigned different sorts of opinions to draft than those they receive later on, and the act of writing many opinions may alter one’s style over time. The data implies that style does change moderately over the course of a Justice’s career—though judicial writing does not necessarily become more readable as Justices gain experience.

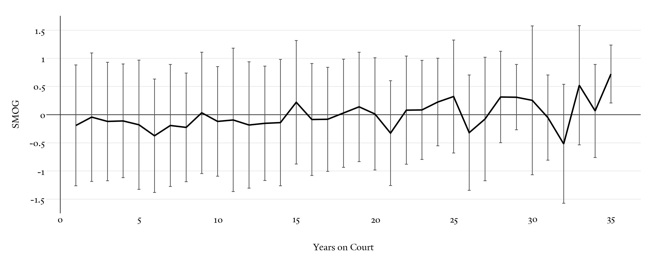

Figure 2 shows the trend in SMOG scores by the number of years a Justice has sat on the Court.16 Because we are interested in seeing potential changes to individual Justices’ styles, the scores are presented as z-scores,17 where each decision’s SMOG value is normalized by the SMOG values of all opinions with the dataset written by that Justice. Normalizing the data in this fashion allows us to chart how SMOG changes over the course of Justices’ careers without having to worry about the fact that each Justice may have starkly different writing styles. In Figure 2, each yearly bar shows the mean (and standard deviation) of the normalized SMOG scores for each year of a Justice’s tenure. So the first bar shows that opinions drafted in a Justice’s first year on the court have a mean SMOG value that is 0.19 standard deviations below their career mean, while opinions drafted in the 35th year (for those who sit on the court that long) have a mean SMOG value 0.72 standard deviations above their career mean. Years of tenure correlates with SMOG scores at the r = 0.07 (p < 0.0001) level. Although the relationship is relatively weak, it suggests that the longer a Justice sits on the court the more difficult to read his or her opinions become.

There are a number of potential explanations for this trend. The population size for Justices decreases at higher tenure levels, because justices eventually leave the court. Justices with more complex writing styles might also be more likely to sit on the Court for longer. Alternately, the act of sitting on the Court might alter writing styles, leading to an increase in average SMOG over time. This could occur as the Justice becomes more comfortable on the bench and focuses less on drafting tight and specific prose. Alternately, as the years go by and the Justice drafts more-and-more opinions and perhaps develops strongly held views in certain areas of law, his or her writing style may become more verbose when dealing with these issues and discussing legal developments.

Figure 2.

smog by tenure

C. Individual Readability Trends over Time

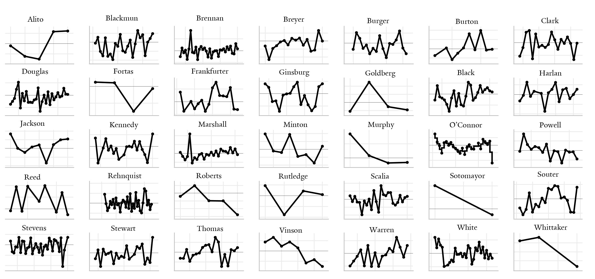

While the average SMOG scores across all Justices increase moderately over time, an individual Justice’s SMOG score might not. Indeed, some remain relatively stable over their careers, while others trend either upwards or downwards. Figure 3 shows the trend in SMOG scores for the thirty-five most recent Justices. The graphs plot z-scores, with each Justice’s opinions normalized over their entire career, so the x-axis represents time, with the horizontal bar representing that Justice’s career mean readability, and each y unit represents one standard deviation.

Figure 3.

individual justice readability over time

For the most part, we see what looks to be random variation across a Justice’s career. For instance, Justices Douglas and Stevens vary consistently around the mean. Some Justices however show SMOG trends, such as Roberts and Vinson, who both appear to write more easily understood prose as their careers advance.

D. Comparing Justices’ Readability

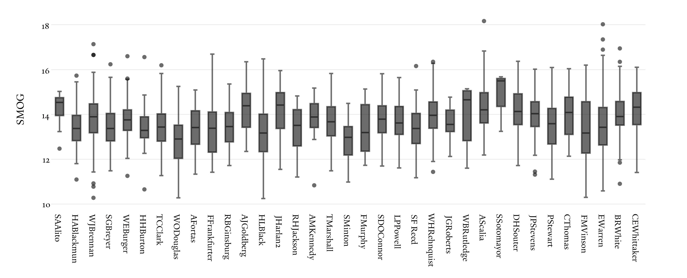

Because the above individual scores are normalized by Justice, they do not permit direct comparison between writing styles. Figure 4 plots each Justice’s SMOG scores in absolute values, enabling comparisons between them.18 Naturally, we see a wide range of SMOG scores for each individual Justice. But we also see some significant variation in how difficult to read individual Justices’ writing styles are. Justice Sotomayor has the highest median SMOG score (15.49), and Justice Scalia has the highest observed value (18.16), while Justices Douglas has the lowest median value (12.91), and Justice Black has the lowest observed value (10.25).

Figure 4.

individual justice readability

The standard deviation for all SMOG scores is 1.04, so the 2-3 SMOG grades of difference we see between the upper and lower median scores shown in Figure 4 represent substantial variation in judicial writing styles. As we would expect from the findings observed when analyzing SMOG values over time, we see recent appointees with relatively high SMOG scores, with many of the older appointees having lower SMOG scores. We also see substantial variation in the range of readability in judicial writing styles. Justices like Alito and Burger have relatively consistent writing styles, as can be seen by the narrow inter-quartile range shown in Figure 4’s boxplots. The difference between Alito’s 75th and 25th percentile SMOG values is only 0.79, while Burger’s is 0.92. Justices Vinson and Rutledge occupy the opposite end of the spectrum with their widely varied opinion readability. The difference between Vinson’s 75th and 25th percentile SMOG scores is 2.32 while Rutledge’s is 2.22.

E. Ideology and Readability

Seeing this variation amongst Justices, the natural question to ask is: why? What drives the variation between writing styles? Most of it is likely due to personal stylistic preferences, education, experience, and training. Some of it might derive from the types of cases assigned to each Justice. These factors certainly explain much of the inter-Justice variation.

While these factors driving variation are difficult to measure objectively, looking to the Justices’ ideological perspectives may offer insight into at least one of the personal attributes that cause complexity in judicial writing. Cognitive studies have provided evidence to show that conservatives have more straightforward cognitive styles than liberals,19 which may affect the way conservative Justices draft their opinions. We can use the data at hand to explore this question.

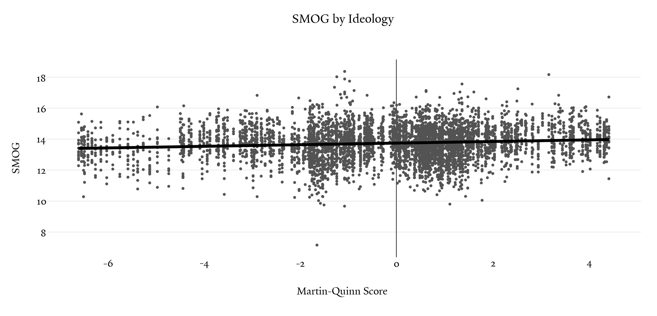

Figure 5 plots individual opinions’ SMOG scores by the Martin-Quinn score for the Justice that authored the opinion. Martin-Quinn scores approximate the ideology of each Justice for each year they are on the Court.20 The scores place the Justices on a continuum with most liberal on the left and most conservative on the right.21 We see no strong relationship between ideology and SMOG, but do note a slight positive correlation (r = 0.11, p < 0.0001).

Figure 5.

smog and ideology

There appears to be a mild but significant relationship between ideology and SMOG. This persists even in a multivariate model that controls for the length of the opinion, whether the vote was split, and the legal issue the opinion deals with,22 suggesting that opinions that score on the conservative side of the Martin-Quinn spectrum are somewhat more difficult to read than those on the liberal side.

Conclusion

Writing is central to the law. This brief Essay has demonstrated some trends within Supreme Court writing styles, exploring how Supreme Court Justices’ writing styles have changed as a whole over time, over individual Justice’s careers, and how styles vary between Justices. We have seen that Supreme Court opinions have grown more difficult to read in recent decades, with a particular spike since 2000, and that conservative-leaning opinions are somewhat more difficult to read than their liberal peers. On the individual level, the longer Justices sit on the court the more complex their writing tends to become. There is also substantial inter-Justice variation, with over two and a half SMOG points separating the medians for the Justices with the highest and lowest median readability scores.

Future work could adopt these methods to examine the writing styles of other legal practitioners. One wonders whether clarity of writing style correlates with the likelihood that a judge will be promoted, or that a lawyer will win cases or make partner.

In legal writing, readability may have an optimal level. High SMOG scores are not necessarily a bad thing. Although Justice Scalia has the highest SMOG score observed and a higher than average median readability, suggesting that his opinions are not easy to read, he is well-known for his strong and distinctive writing style, and he has written extensively on effective legal communication.23

Although true gobbledygook is probably best avoided, to some extent high scores in the Simplified Measure of Gobbledygook may be an unavoidable part of the practice of modern law. The law frequently engages with complex subject matter, and the legal issues that the Supreme Court deals with are often the most nuanced. In explaining these issues a degree of complex language is almost inevitable. Indeed, some might be thankful that the average Supreme Court opinion since 1946 has a SMOG value of only 13.75, meaning that the language is geared towards a college student reading level. All that said, the upward trend demonstrated in Section II.A shows some cause for concern. While some degree of gobbledygook may be necessary in legal writing, we do not want judicial opinions to become so complex as to require SMOG warnings.

Ryan Whalen is a Law & Science Fellow at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law. He is also a J.D./Ph.D. Candidate at Northwestern University, where his primary research focuses are information and innovation policy and intellectual property law.

Preferred Citation: Ryan Whalen, Judicial Gobbledygook: The Readability of Supreme Court Writing, 125 Yale L.J. F. 200 (2015), http://yalelawjournal.org/forum/judicial-goobledygook.

William W. Schwarzer, Forward to the First Edition to Fed. Judicial Ctr., Judicial Writing Manual: A Pocket Guide for Judges, at vii (2d ed. 2013) (“The link between courts and the public is the written word. With rare exceptions, it is through judicial opinions that courts communicate with litigants, lawyers, other courts, and the community. Whatever the court’s statutory and constitutional status, the written word, in the end, is the source and the measure of the court’s authority.”).

CourtListener was chosen because it offers bulk downloads of opinions in machine-readable form, allowing for relatively straightforward computational analysis of the opinions’ text. See About, CourtListener (Aug. 27, 2015, 5:26 PM), http://www.courtlistener.com/about [http://perma.cc/NC8M-39UH]. The 1946 start date was used because many of the below analyses depend on both the textual data retrieved from CourtListener and other data about the Justices retrieved from the Supreme Court Database, which has coverage from 1946 on. Because the CourtListener data does not clearly distinguish between majority and dissent opinions, we can only be certain of authorship in cases where no dissent was filed. Thus, the analyses below that do not look to a specific Justice’s writing style use the full 6,206 opinions, while those that analyze a specific Justice’s writing style rely only on opinions in which no dissents were filed.

McLaughlin, supra note 4, at 645. The formal definition of SMOG is [equation available in PDF version of this Essay]. See SMOG, Wikipedia (Nov. 19, 2015, 12:48 PM), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMOG [http://perma.cc/K8U7-D459]. The SMOG score of the above-the-line text in this essay is approximately 9.4.

SMOG calculation requires parsing text into distinct sentences and measuring the number of syllables in each word. I used the Python Natural Language Toolkit sentence tokenizer to separate opinions into sentence units, see Natural Language Toolkit, http://www.nltk.org [http://perma.cc/4F4N-XX8J], and subsequently used the Carnegie Mellon University Pronouncing Dictionary to lookup the number of syllables in each word, see CMU Pronouncing Dictionary, http://www.speech.cs.cmu.edu/cgi-bin/cmudict [http://perma.cc/WJ4C-E9BS]. In instances where words were not in the Carnegie Mellon dictionary, I used a simple algorithm to estimate the number of syllables in the word. This simple algorithm involved removing the usually silent “e” from the end of the word and subsequently counting vowel groups in the word. A vowel group is defined as any number of vowels at the beginning or end of the word, or any number of vowels preceded and succeeded by consonants. For example, the word “banana” contains three vowel groups (each “a” fits the definition). The algorithm would use this information to estimate that “banana” is a three-syllable word.

To ensure that a peculiarity of the SMOG formula was not driving results, I also measured readability using the Automated Readability Index measure with similar results. See R.J. Senter & E.A. Smith, Automated Readability Index (Aerospace Med. Research Laboratories 1967).

Pearson correlation coefficients range from -1 to +1. A score of -1 demonstrates that two variables are perfectly negatively correlated (that is, a decrease in variable a corresponds to a linear increase in variable b). A score of 1 demonstrates that two variables are perfectly positively correlated, and a score of 0 suggests no correlation. The observed score of 0.29 shows that the year and the SMOG scores are positively correlated, so as the years increase, so do the SMOG scores. That the p value is so low (less than 0.0001) shows that we can be confident this correlation is statistically significant.

Records of which Justice wrote which opinion were obtained from the Supreme Court Database. Harold J. Spaeth et al., 2014 Release 01, Sup. Ct. Database (July 23, 2014), http://supremecourtdatabase.org/data.php [http://perma.cc/2UE2-24KG].

Z-scores normalize the values for each Justice by converting his or her SMOG scores to units of standard deviation. So, a z-score of one is equivalent to a SMOG score that is one standard deviation above that Justice’s mean, while a z-score of negative one is one standard deviation below that Justice’s mean. By normalizing the scores in this manner, we can then look to the trend over time across Justices.

See, e.g., Philip E. Tetlock, Cognitive Style and Political Ideology, 45 J. Personality & Soc. Psychol. 118, 123 (1983) (showing that conservative senators tend to make significantly less complex statements than their liberal or moderate colleagues); Philip E. Tetlock et al., Supreme Court Decision Making: Cognitive Style as a Predictor of Ideological Consistency of Voting, 48 J. Personality & Soc. Psychol. 1227, 1227 (1985) (showing that Justices with more liberal and moderate voting records exhibited more integratively complex styles of thought).

In an ordinary least squares model with SMOG as the dependent variable, including terms to control for the legal issue, the number of words in the opinion, and whether the vote was split, an increase of 1 point in Martin–Quinn scores corresponds to an increase of 0.96 on the SMOG scale. Legal issue data was retrieved using the Supreme Court Database’s “Issue Area” variable. Spaeth et al., supra note 16.