Triptych’s End: A Better Framework To Evaluate 21st Century International Lawmaking

How does the United States enter and exit its international obligations? By the last days of the Obama Administration, it had become painfully clear that the always imaginary “triptych” of Article II treaties, congressional-executive agreements, and sole executive agreements, which has guided foreign relations scholars since the Case Act, is dying or dead. In 2013, as State Department Legal Adviser, I argued that:

In the twenty-first century . . . we are now moving to a whole host of less crystalline, more nuanced forms of international legal engagement and cooperation that do not fall neatly within any of these three pigeonholes . . . . [O]ur international legal engagement has become about far more than just treaties and executive agreements. We need a better way to describe the nuanced texture of the tapestry of modern international lawmaking and related activities that stays truer to reality than this procrustean construct that academics try to impose on a messy reality.1

This Essay seeks to offer that better conceptual framework to evaluate the legality of modern international lawmaking. It illustrates that framework through two recent case studies of modern U.S. diplomacy: the Paris Climate Change Agreement and the Iran Nuclear Deal.

As we move into the uncertain legal terrain of the Trump Administration, this Essay also examines how easily the new Administration can exit these innovative international arrangements.2 Notwithstanding the incoming Administration’s rhetoric, I conclude that early exit is easier said than done. Both agreements are stickier than might be assumed, because each has substantially reshaped expectations and default patterns of behavior in its issue area. Whether or not the United States honors its commitments will depend not just on which elected officials lead the country at any particular time, but on whether and how a diverse group of stakeholders in an ongoing transnational legal process use tools available to them to hold America to its commitments. Whether the President is internationalist or isolationist, entering or exiting international obligations, my point remains the same: going forward, the fast-changing model of twenty-first century international lawmaking demands fewer formalistic tests and more pragmatic standards that will enable a more realistic sharing of constitutional powers.

I. the obsolescence of the triptych

We have come a long way since anyone imagined Article II treaties to be the primary, much less the exclusive, means for the United States to enter international law obligations.3 It was long ago settled that congressional-executive agreements should be treated as instruments legally interchangeable with Article II treaties for conducting and completing diplomatic deals.4 The last gasp for the legal indispensability of treaties came in the 1990s, when Laurence Tribe famously called unconstitutional the congressional-executive mechanism by which the Clinton Administration joined the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).5 His theory met near-universal rejection, including by the overwhelming majority of the legal academy. These scholars correctly reasoned that our constitutional practice had developed sufficiently to permit binding agreements entered into by the Executive and approved by majorities of both houses of Congress, particularly where Congress is exercising its foreign commerce power.6 Indeed, the United States has used congressional-executive agreements as the technique of choice to conclude a whole range of international economic arrangements: not just NAFTA,7 but also the Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO)8 and the 1945 Bretton Woods Agreement, which “did nothing less than create the foundations of a new world economic order.”9

Nor, given the huge political difficulty of securing congressional majorities even for previously uncontroversial trade agreements,10 are formal congressional-executive agreements the sine qua non of international lawmaking. Under the political deadlock between the President and Congress during the Obama Administration, the number of Senators needed to block consideration of such an agreement has declined over time from fifty-one (a majority of the Senators), to forty-one (the number needed to sustain a filibuster), to ten (the number usually needed to prevent a congressional-executive agreement from being voted out of the relevant committee), to one (a single Senator or Senate staffer preventing an otherwise uncontroversial congressional-executive agreement from receiving unanimous consent).11

True “sole executive agreements”12 or agreements based solely on the President’s plenary constitutional authorities—the third category of the triptych—remain extremely rare. Legal scholars traditionally cite a few iconic sole agreements, like Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 Destroyer-for-Bases deal13 or the early twentieth-century Soviet deals in United States v. Belmont and United States v. Pink.14 But in practice, few modern-day presidents ever claim to be making a controversial agreement based solely on their own plenary constitutional authority, particularly when Congress has already legislated elsewhere regarding the same subject. Instead, the agreement-making President almost always—and often with good reason—claims to be making the agreement supported by express or implied congressional approval or receptivity, evidenced by other related congressional actions in the subject-matter field.

Yet despite these trends, many foreign relations scholars and pundits still fetishize the triptych. They argue that a particular international lawmaking arrangement they don’t like must be unconstitutional because they cannot easily place the agreement in one triptych box or another. In recent years, more discerning scholars have started to recognize the intellectual limitations of the triptych, but have proposed to address the shortcomings by proliferating additional categories: such as “ex ante congressional executive agreements” and “ex post congressional executive agreements,”15 “executive agreements plus,”16 and the like. Some well-meaning scholars have even gone so far as to suggest that innovative international arrangements designed to build complex regulatory regimes or to grow bilateral confidence with long-time adversaries, such as the Paris Climate Change Agreement or the Iran Nuclear Deal, must pose a “threat to the very idea of constitutional government.”17

In my view, such hyperbole substitutes unnuanced pigeonholing for more nuanced understandings of the many complex real-world ways by which the Executive now seeks to make—and Congress now signals its acceptance of—international commitments with foreign partners. Witness, for example, the recent tempest surrounding the Executive’s authority to enter into the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), a multilateral agreement on enforcing intellectual property rights.18 Although much of the opposition derived from policy disagreements regarding the ACTA’s substantive goals, a surprisingly large number of law professors expressed their opposition by questioning the Executive’s legal authority to even enter the agreement.19 They said, in effect, “I don’t see an express ex ante congressional authorization, so it can’t fit into the congressional-executive agreement box, nor does this look like a traditional topic for a sole executive agreement. Since it falls between the stools, that must mean the United States lacks the legal authority to enter the agreement!” What this form of reasoning misses is that the tidy triptych grossly oversimplifies reality. The United States enters into a plethora of international agreements with other countries every year that are consistent with, and that certainly can be implemented under, existing domestic law, but that do not fall neatly into these three boxes.20 The real reason the arrangement does not fit neatly into an existing conceptual box is because of the simplistic way in which the box has been conceived.

Looking back, a simple bureaucratic snafu caused much of the Obama Administration’s public relations problem with the ACTA. When the agreement’s legal form was first challenged by a member of Congress, an agency counsel’s office less familiar with the nuances of foreign relations law wrote the Member an uncleared letter asserting that the ACTA was a “sole executive agreement,” which plainly it was not. To clarify the situation, as State Department Legal Adviser, I wrote a follow-up letter that gave three better reasons why the State Department thought the ACTA was plainly lawful: general preauthorization, consistent executive practice, and legal landscape.21

First, general preauthorization: while Congress did not expressly pre-authorize this particular agreement, it did pass legislation calling on the Executive to “work[] with other countries to establish international standards and policies for the effective protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights.”22 Second, consistent executive practice: as our letter surveyed, the political branches have dealt with similar agreements in the same subject matter area over time, and found that Congress’s call for executive action to protect intellectual property rights arose against the background of a long series of similar agreements on the specific question of intellectual property protection, which were in fact concluded in similar fashion and without congressional objection. So what we saw in practice resembled what I had previously called “quasi-constitutional custom”—a widespread and consistent practice of Executive Branch activity that Congress, by its conduct, has essentially accepted.23

Third, legal landscape: the State Department and the United States Trade Representative (USTR)24 had determined that the negotiated agreement fit within the fabric of existing law, was fully consistent with existing law, and did not require any further legislation to implement. In this sense, the ACTA resembled the Algiers Accords that secured the release of American hostages in Iran, whose constitutionality was broadly upheld in the Supreme Court’s 1981 decision in Dames & Moore v. Regan.25 There, the Court relied not on any particular express ex ante congressional authorization, but rather on “closely related” legislation enacted in the same area and a long history of Executive Branch practice of concluding claims-settlement agreements. Although the Algiers Accords, like ACTA, did not fall neatly into any of the three traditional constitutional “boxes,” the Dames & Moore Court ignored the boxes, instead finding a broader “legislative intent to accord the President broad discretion.”26

More than a quarter-of-a-century ago, I criticized this “implicit authorization” argument,27 arguing that this language should have been cabined to the specific issue in that case: settlement of international claims. But after thirty-five years, the Court’s language has not been so narrowly construed, and this and other Supreme Court opinions following this reasoning remain on the books. In essence, Dames & Moore concluded that so long as the Executive acts consistently with “the general tenor of Congress’ legislat[ive framework] in the” particular issue area, and there is “a history of congressional acquiescence in conduct of the sort engaged in by the President” and “no contrary indication of legislative intent,”28 Congress has effectively licensed a permissible space for executive action in that particular issue area. In that space, the President has greater constitutional freedom to negotiate and conclude certain kinds of international accords without having secured prior, specific congressional approval. By so saying, Dames & Moore seems to have recognized a modern truth: that Congress cannot and does not pass judgment on each and every act undertaken by the Executive that has external effects. Given the multiple ways in which the Executive may act, Congress must also express its acceptance or approval for international lawmaking through more than three formal mechanisms. To function effectively, as in any institutional marriage, one partner must necessarily afford the other a zone of discretion that is signaled by such broader signposts as general preauthorization, consistent practice, and commonly understood “rules of the road.”

II. a better framework: new and legally binding commitments, degrees of congressional approval, and constitutional allocation of substantive authority

What all this suggests is that foreign relations scholars should now dispense with the transsubstantive triptych, which is no longer a meaningful—and at times is a positively misleading—way of describing the multifarious ways in which the United States currently engages in international lawmaking. Nor do I think the problem is adequately solved by creating new pigeonholes like “executive agreement plus.”29 It is hard to see why four, five, or six boxes are intellectually superior to three.

Instead, we should shift to a more realistic, issue-specific, and agreement-specific conceptual framework that better reflects how the current process of congressional approval for, and acceptance of, Executive Branch international lawmaking actually works. In my view, that framework should account for three factors: (1) whether the agreement entails new, legally binding obligations; (2) the degree of congressional approval for the executive lawmaking; and (3) the constitutional allocation of institutional authority over the subject matter area at issue.

1. Whether the Agreement Entails New, Legally Binding Obligations:

The first factor asks: how new are the commitments being assumed (or are they already required under existing law?), and how legally binding are these international commitments? In other words, does the new commitment legally obligate the signatory government to do anything it was not already obliged to do? Only if we make new legal obligations does an executive action have the potential to be like treatymaking, which constitutionally requires congressional approval. If the only international obligation that the Executive Branch assumes is to carry out domestic legal obligations that already exist, there seems little reason why new congressional approval should be required: the United States is only reaffirming an existing constitutional obligation to obey domestic law.

Whether a particular set of commitments is lawful should be both subject matter-specific (e.g., is this agreement about war, trade, or intellectual property?), and agreement-specific (e.g., are the particular provisions in question legally or politically binding?). If the international commitment being assumed is only political, and neither new, legally binding, nor domestically enforceable, the obligations being created are diplomatic, not contractual, and can lawfully be made by the President alone, operating against a broad background of legislative acceptance of the kind found in Dames & Moore.

2. Degree of Congressional Approval of Executive Lawmaking:

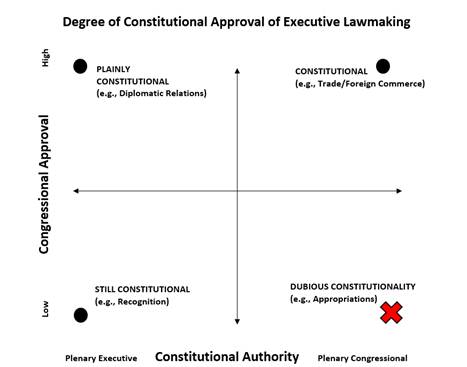

On further reflection, the triptych is an inadequate proxy for representing the intersection of not one, but two spectrums of political interests. Put together, the two spectrums look roughly as below. The first, vertical spectrum—depicted by the y-axis in the chart—denotes the degree of evidence of the extent of congressional approval for a particular presidential action, running from zero evidence (at the bottom of the chart) to unambiguous, widespread, and specific evidence of congressional approval (at the top of the chart). To the extent that this vertical spectrum roughly parallels the traditional triptych, it is because the triptych itself was a proxy for Justice Jackson’s tripartite framework in his Youngstown concurrence. That opinion,30now enshrined in the majority opinion in Dames & Moore, famously describes a spectrum running from congressional approval to congressional silence, with Article II treaties representing a special category created by the Framers, who chose to deem supermajority approval in the Senate as a valid, constitutional alternative to approval by legislative majorities in both houses.

Figure 1.

|

3. Constitutional Allocation of Institutional Authority over the Subject Matter:

On reflection, the greatest failing of the triptych is that it has purported to be transsubstantive. But in fact, the degree of congressional approval required to legalize any particular presidential agreement is substance-dependent: it depends on which particular issue of substance is being affected, and on which branch of government has substantive constitutional prerogatives regarding that area of foreign policy.31 This second, horizontal spectrum—depicted by the x-axis of the graph—runs from textual reservoirs of exclusive presidential authority under the Constitution (e.g., the recognition power) on the far left, to countervailing zones of plenary congressional authority (e.g., the foreign commerce power or the appropriations power) on the far right.

Putting these two spectrums together, they show that presidential lawmaking will be constitutional if strongly supported by congressional approval. Indeed, the top portion of the graph simply depicts Youngstown Category One: where the President’s “authority is at its maximum, for it includes all that he possesses in his own right plus all that Congress can delegate.”32 Whether congressional support is even necessary is subject-matter specific—e.g., toward the left side of the graph, the President has powerful claims of plenary authority even without congressional action. In such areas, the President could even operate in the face of express congressional disapproval because he has clear plenary power (e.g., maintenance of diplomatic relations) that may allow him to act even over congressional objection because (as in Youngstown Category Three) “[the President] can rely only upon his own constitutional powers minus any constitutional powers of Congress over the matter.”33 But if there is both low congressional approval and the subject matter of the dispute is uniquely within Congress’ constitutional authority (as in the lower right quadrant of the graph above), the agreement will be unconstitutional. Finally, the middle range on the y-axis reflects Justice Jackson’s Youngstown Category Two: where the President acts in the face of congressional silence with regard to the specific presidential action being contemplated. But in this zone, it is hard to make categorical pronouncements regarding unconstitutionality because, as Professor Tribe has noted, “Youngstown offers no meaningful baseline against which to assess the operative legal significance of Congress’ silence.”34

The upshot of this analysis may be summarized as follows: (1) if a particular agreement does not embody new, legally binding commitments, it will almost certainly be lawful even with little or no congressional approval; (2) but if a particular agreement does embody new, legally binding international commitments, the constitutionality of that arrangement will depend on where the subject matter of the agreement and the degree of congressional approval fall on the scattergraph above. The further an agreement falls into the bottom right quadrant—e.g., a sole executive agreement attempting to mandate appropriations—the more dubious its constitutionality will be. In evaluating the extent of congressional approval for an agreement of this type, one should look to factors similar to those applied in Dames & Moore: general preauthorization, consistent executive practice, and legal landscape. Instead of the two-dimensional triptych, this approach offers a more realistic, issue-specific, and agreement-specific way to reflect how political approval for Executive Branch international lawmaking actually works.

III. two case studies: paris and iran

To see how this subject-dependent, agreement-specific approach would work, let me apply it to the two most important and controversial diplomatic arrangements of the Obama Administration: the Paris Climate Change Agreement and the Iran Nuclear Deal (or Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)). Conspicuously, each was—wisely, in my view—concluded with almost deliberate non-reference to the tripartite “triptych” framework. Foreign relations scholars have spilled much ink debating whether they are sole executive agreements, congressional-executive agreements, or something else altogether.35 But those analyses miss the real question: is applying the “triptych” even meaningful, inasmuch as it implies that legislative authority in the foreign affairs area sits on isolated stools? Or should we instead apply the criteria above: (1) where do these agreements fall within the space sketched by the intersecting spectrums of congressional authority and approval, indicated by general preauthorization, legal landscape, and consistent executive practice? And (2) how new or legally binding are these commitments?

A. The Paris Climate Change Agreement:

Take first the Obama Administration’s efforts to renew the United States’ engagement in international diplomacy addressing the threat of global climate change. Those efforts, pioneered by Global Climate Change Envoy Todd Stern, began to take hold in Copenhagen in 2009 and recently culminated in the 2015 Paris Climate Change Agreement (PCCA), which entered into force in November 2016. For constitutional purposes, the PCCA’s legality is supported by the factors outlined above.36

1. General Preauthorization:

The Paris Deal was negotiated under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), a treaty with 195 parties to which the Senate gave its advice and consent in 1992. In 2011, the parties adopted the Durban Platform, which launched a new round of negotiations to develop “a protocol—another legal instrument—or an agreed outcome with legal force under the UNFCCC applicable to all Parties.”37 The Durban Platform specifically provided that this new legal or quasi-legal instrument would be “under the [UNFCCC] Convention.”38 Hence, the subsequent Paris agreement was not based on sole executive power, but rather, preauthorized by a duly ratified Article II treaty, i.e., negotiated within the scope of the Senate’s original advice and consent to the 1992 UNFCCC.

2. Legal Landscape:

In addition, Congress expressed its support for climate change negotiations in: (1) the Global Climate Protection Act of 1987, which asserted the need for “international cooperation aimed at minimizing and responding to adverse climate change;”39 (2) the Clean Air Act (which the Supreme Court held in Massachusetts v. EPA40 authorized the EPA to regulate carbon dioxide emissions as a pollutant), thereby allowing the President to argue that he could negotiate international agreements as a necessary adjunct to regulating domestic emissions, and (3) section 115 of the Clean Air Act, which authorized federal action reciprocally with other nations to address “international air pollution,” namely, transboundary pollution causing damage within the United States.41

3. Consistent Executive Practice:

Presidents of both parties have negotiated similar environmental agreements addressing pollution as executive agreements without express congressional approval, including the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (and multiple subsequent protocols), the U.S.-Canada Air Quality Agreement, and the Minamata Convention on Mercury.

4. New, But Not Legally Binding, Commitments:

Operating under these precedents, the United States first unsuccessfully went down the road of seeking legally binding treaty commitments in trying to adopt the Kyoto Protocol. But in 1997, by a 95-0 vote, the Senate adopted the Byrd-Hagel Resolution, instructing that the United States should not join any new climate agreement that would mandate emission reductions for developed but not developing countries. That made it clear that a follow-on Kyoto Protocol would be dead on arrival, and in 2001, President George W. Bush announced that the United States did not intend to become a Kyoto party. The United States’ experience with the Kyoto Protocol led to the daring change in diplomatic approach to international treaty commitments at the 2009 Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen. President Obama’s and Secretary Clinton’s dramatic last-minute personal diplomacy forced a consensus among all the major economies on the Copenhagen Accord: a political, not legally binding, document that moved away from the more inflexible Kyoto Protocol paradigm. For the first time in decades of climate diplomacy, the Copenhagen Accord secured meaningful commitments to address climate change from developed and developing countries alike on several key elements, including a global aspirational temperature goal, international assessment procedures, and a new “green” global climate fund. While not legally binding, the Copenhagen outcome paved the way for the Cancun Agreements the following year—which in 2011, in a still non-legally binding way, incorporated and elaborated the Copenhagen Accord’s main elements—and then the Durban Platform.

These steps led to the 2015 Paris Conference, where the parties achieved an historic accord not by entering a binding legal agreement but, rather, by doing the opposite. Indeed, the most dramatic moment of the Conference came on the final day, when the United States hastened to “correc[t] an error in the text, which had converted a provision intended to be non-binding into a binding obligation, by using the verb ‘shall’ rather than ‘should.’”42 As concluded, the Paris Agreement states no legally binding emissions caps, declaring only that member states “should” meet such targets. Nor are the financial commitments of the Accord binding, but rather, only follow “in continuation of the existing obligations under the UNFCCC.” Finally, those relatively few “legally binding provisions [included in the Paris Agreement] are largely procedural in nature and in many instances are duplicative of existing U.S. obligations under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change,”43 and therefore could be fully implemented based on existing U.S. law.

It thus seems plain that the Paris Accord is lawful, inasmuch as it is adopted within the framework of an Article II treaty, the UNFCCC, which the United States ratified twenty-four years ago with the advice and consent of the Senate; follows broad congressional directives in the Clean Air Act and the Global Climate Protection Act; and mostly assumes obligations that, while new, are not legally binding under domestic law. The President can implement the new legal obligations assumed under the Paris Agreement merely by carrying out pre-existing domestic legal obligations. Even if new legal obligations were entailed, the Agreement would still fall somewhere in the top right quadrant of the graph above—constitutional because 1) congressional approval is high even if Congress has a strong claim to constitutional authority over the subject matter, and 2) it is supported by the same three factors that supported the legality of the ACTA: general preauthorization, legal landscape, and consistent executive practice.44

B. The Iran Nuclear Deal (JCPOA):

The July 14, 2015 comprehensive nuclear deal between the P5+1 (United Kingdom, France, China, Russia, the United States, Germany, and the European Union) and Iran (known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or “JCPOA”) consists of the agreement itself and five technical annexes.45 In brief, the JCPOA envisions actions by Iran, the United States, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and key allies including the other Permanent Security Council members, Germany, and the European Union. After extended negotiation, Iran agreed to specified limits on its nuclear development program in exchange for the United States undertaking to lift both unilateral U.S. sanctions and the other nations agreeing to lift international sanctions that had been imposed through the United Nations. For present purposes, the factors outlined above are again most relevant: degree of congressional approval, constitutional allocation of authority, and the legal character of the obligations being assumed.

First, there is ample domestic legal authority for all the actions the United States commits to undertake under the JCPOA, in particular, for the President to suspend economic sanctions pursuant to waiver authority provided by Congress, so long as Iran fulfills its stated commitments.46 This is not just “general preauthorization,” but specific statutory authorization of the Youngstown Category One kind.47

Second, as in Dames & Moore,48 the legal landscape clearly envisions the President exercising these statutory authorities. While the Constitution’s allocation of substantive authority grants Congress undoubted subject matter authority over foreign commerce, and hence, economic sanctions, Congress has just as undeniably delegated implementation of these authorities by enacted statutes to the President on the matters in question.49 Congress has thereby granted the President specific statutory authority to waive existing domestic law sanctions against Iran when he determines it is in the national interest to do so, including if Iran has done what it has said it would do with respect to abating development of highly enriched weapons-grade uranium.

Third, the JCPOA is a political, not a legally binding, commitment in both form and substance. As Duncan Hollis and Joshua Newcomer have detailed, such political commitments have long been common in executive practice.50On matters of substance, the parties went out of their way to style the obligations as “voluntary”—things they “will do” (not “shall do”)—and carefully avoided all the procedural trappings of a binding convention in favor of a political commitment to do something, so long as another strategic partner has taken the steps it has agreed to take.

Simply put, the Iran Nuclear Deal is a confidence-building device designed to shift from a pattern of confrontation toward a pattern of cooperation with Iran. If Iran does what it says it will do under the JCPOA, the President has ample statutory authority to waive the sanctions in question, and clear constitutional authority to make a nonbinding political commitment that the United States will not re-impose such sanctions under the terms of the JCPOA. The only new piece of legislation enacted in response to the JCPOA, the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act (“Corker/Cardin” bill),51 does not undermine the President’s legal authorities; if anything, it added to them.52 The heart of that bill is a classic “report-and-wait” provision: the only effect the bill had on the President’s existing statutory waiver authority over Iran sanctions was to postpone his exercise of that waiver authority until sixty days had passed without Congress enacting a joint resolution of disapproval, which it did not enact.53

Thus, the JCPOA would fall squarely into the top right quadrant of the graph above. It is constitutional because the JCPOA, like the Paris Agreement, conspicuously does not require the United States to undertake any new or legally binding obligations as a matter of international law and because even if Congress has an undeniably strong claim to constitutional authority over the subject matter (economic sanctions), congressional approval through delegated statutory authorities is high.

IV. can a new president “cancel” these agreements?

During the 2016 presidential campaign, President-Elect Donald Trump promised to “cancel” the Paris Agreement54 and “rip up” the Iran Nuclear Deal.55 But reality is not as simple as rhetoric. In support of this threat, thirteen Senators wrote to Secretary of State John Kerry citing the triptych, claiming that the Paris Agreement could be easily dissolved, because the United States signed it as a “sole executive agreement[] [which is] one of the lowest forms of commitment the United States can make and still be considered a party to an [international] agreement.”56 The forty-seven Senate Republicans who wrote to the leaders of Iran attacking the JCPOA before it was completed similarly engaged in a hornbook recitation of the triptych.57

But in both cases, the Senators’ reasoning simply confirms the practical obsolescence of formalistic triptych reasoning. To the extent that these two deals constitute nonbinding political agreements made by the Executive alone, of course, both could be terminated by a new President as a matter of domestic law. But both letters misunderstand the modern process of international lawmaking by ignoring the interactive way in which such agreements are actually implemented and confusing the domestic and international dimensions of the United States law of international agreements.

A. The Paris Climate Change Agreement:

As a matter of international law, the Paris Agreement took force on November 4, 2016, just four days before the United States presidential election, and has now been approved by some 109 countries representing 76% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.58 Under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, a single state party cannot invalidate an entire multilateral agreement; it can only withdraw from the treaty in accordance with its terms.59 The specific terms of the Paris Agreement do not allow a party to withdraw from the agreement except by giving “written notification” “any time after three years from the date on which this Agreement has entered into force for a Party,” with “[a]ny such withdrawal . . . tak[ing] effect upon expiry of one year from the date of the receipt . . . of the notification of withdrawal.”60 Thus, even had the President-Elect not recently signaled his willingness to “take a look” at staying in the Paris Agreement,61 as a matter of international law, he could not formally withdraw the United States from its Paris obligations until the start of the next four-year presidential term, when a new president less hostile to the Paris Agreement might be taking office.

One Trump advisor has apparently claimed that the new Administration could “issu[e] a presidential order simply deleting the U.S. signature from the Paris accord.”62 But once again, it is not so easy. The George W. Bush administration famously tried to “unsign” President Clinton’s 2000 signature of the Rome Statute to the International Criminal Court.63 But after much churning, as of January 2017, the United States’ signature remains on the Rome Statute and the U.S. government’s official position remains that there has not been “what international lawyers might call a concerted effort to frustrate the object and purpose of the Rome Statute.”64

Some Trump advisors have apparently proposed that the United States give notice to withdraw from the UNFCCC, the framework treaty underlying the Paris Agreement, which permits withdrawal after only one year.65 But that would be a far more radical step, reaching far beyond President-Elect Trump’s campaign promise simply to “cancel” Paris. To do so, the new Administration would undo extensive work by the last three Republican Administrations. It would necessarily abandon developments initiated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change with the support of the Reagan and George H.W. Bush Administrations and disengage entirely from—losing all leverage upon—the global climate change process, something that even the George W. Bush administration declined to do in withdrawing from the Kyoto Protocol. To do so would be particularly difficult politically for the new Administration, given that the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and the European Union are major players in the climate change process, and would retain considerable power to subject the United States to carbon-offset tariffs and similar penalties, should the United States default on its Paris obligations.66

Nor, as a matter of domestic law, is it entirely clear that the President has constitutional power to withdraw from either the Paris Agreement or the UNFCCC without congressional participation. Admittedly, the precedent most on point, the Supreme Court’s summary disposition nearly four decades ago in Goldwater v. Carter,67 dismissed a Senator’s challenge to the President’s decision unilaterally to terminate a bilateral mutual defense treaty with Taiwan in accordance with its terms on political question grounds. But in Goldwater, the political branches had not yet reached “constitutional impasse,” and only one Justice voted on the merits to uphold the President’s treaty termination power, based on the peculiar fact that that case—unlike climate change—involved recognition of foreign governments, an issue over which the President plainly exercises plenary constitutional power.68 In the protracted Zivotofsky litigation, the Court recently declined a similar political question challenge to an assertion of the President’s recognition power.69

A more likely scenario may be that without formally withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, a Trump Administration simply abandons the Obama Administration’s commitments by refusing to implement rules, incentives, and programs designed to ensure that the United States lives up to its Paris climate obligations. The Trump Administration could, for example, dramatically weaken the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or renege on the Obama Administration’s non-binding promises to meet its Paris obligation through the set of EPA regulations known as the Clean Power Plan (CPP). These include an agency rule that pushes for interstate cap-and-trade, and for states to build fewer coal-burning plants while creating greater renewable-energy capacity. The EPA’s authority to implement the Clean Power Plan was stayed 5-4 by the Supreme Court earlier this year (with the late Justice Scalia in the majority); at this writing, the D.C. Circuit, sitting en banc (without Chief Judge Garland), is deciding whether the EPA has authority to implement the CPP, with a decision likely in early 2017.70 If, as seemed possible after oral argument, the en banc circuit court should rule in favor of the EPA’s authority under the Clean Air Act to meet the United States’ global climate obligations, the issue seems likely to go to the Supreme Court. Even if the new Administration should decline to defend the Clean Power Plan there, the Court could appoint an amicus curiae to represent and vindicate the prior administration’s position, as was done in the famous case of Bob Jones University v. United States.71 If no ninth Justice has been confirmed by then, the D.C. Circuit’s ruling could well be affirmed by an equally divided Supreme Court.

Should a Trump EPA back away from supporting the Clean Power Plan, litigation would almost certainly ensue. Plaintiffs would claim that the President has failed to faithfully execute the United States’ international legal obligations under the Paris Accords, with the agency’s claim to Chevron deference compromised by competing agency interpretations of the same Clean Air Act provisions. Undoing EPA rules that mandate fuel and energy-efficiency standards would likely require a new regulatory process subject to notice-and-comment rulemaking and stakeholder inputs.72 Many United States climate stakeholders other than the federal government—such as states and localities73 and private clean-energy entrepreneurs74—have shifted their expectations and energy goals toward meeting the Paris targets. “Clean energy costs have dropped dramatically—even since 2008, costs for wind are down 40 percent, solar photovoltaic 60 percent, and LED lighting 90 percent. These cost reductions make action to shift toward clean energy much easier and make the benefits to health and jobs very clear.”75 These alternative, nonfederal stakeholders will almost surely generate an alternative plan of litigation and emissions reduction designed to keep U.S. emissions within striking distance of the promised U.S. Nationally Determined Contribution at the next global accounting under the Paris Agreement.76 Even if the United States should fall into arrears on emissions reductions or its green climate fund contributions, as it has done in the past with respect to the payment of U.N. dues, other domestic and international stakeholders can exert pressure to force this Administration and the next to make up the difference in a more climate-friendly administration.

In sum, to the extent that “real progress on decarbonization primarily depends upon specific domestic energy, industrial, and innovation policies,” then “[e]ven should the next [A]dministration withdraw from the Paris Agreement and abandon the Clean Power Plan, the United States might outperform the commitments that the Obama [A]dministration made in Paris if it keeps the nation’s nuclear [power plant] fleet online, continues tax incentives for deployment of wind and solar energy, and stays out of the way of the shale [energy] revolution.”77 The shift in investment patterns toward renewable energy may have reached a point where it is very hard to reverse. The key point, as one commentator put it, is that “there is no reason to believe that people will want good health, better technologies, or clean air less just because of a change in administration.”78

The larger point is that once a nation becomes deeply embedded in an evolving international regime, its default path of least resistance becomes compliance. There are many ways for a nation to satisfy a global commitment, and in none of them is the United States federal government the only actor. The Paris Agreement created a framework within which transnational actors repeatedly interact at an international level in a way that continually spurs the development of emission reduction norms and policies at the domestic level. These norms operate not just in federal, but also in mutually reinforcing state, local and private initiatives. I long ago described a pervasive phenomenon in international affairs that I call “transnational legal process,” which holds that international law is primarily enforced not by coercion, but by a process ofinternalized compliance.79Nations tend toobeyinternational law because their government bureaucracies adopt standard operating procedures and other internal mechanisms that foster default patterns of habitual compliance with agreed upon norms. That “bureaucratic stickiness” will create default resistance to disruption that the new Administration will have to negotiate in every policy area, mindful of its weak coalition, minority electoral support, and limited political capital. If the President-Elect tries to change course too sharply, he will encounter deep resistance and may be forced to moderate his positions in order to preserve scarce political capital.

B. Iran Nuclear Deal (JCPOA):

A similar pattern seems likely to develop with respect to the Iran Nuclear Deal. Under domestic and international law, the JCPOA is a politically, notlegally, binding arrangement, given effect largely through executive orders that suspended nuclear-related sanctions in exchange for Iran dismantling key elements of its nuclear program under the watch of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The success of the arrangement depends not on whether it is legally binding, but on whether the IAEA verifies Iran’s continuing compliance with the strict restrictions that were put in place. It thus means little for the new Administration to pronounce its intention to “rip up” the JCPOA, given that the President’s domestic legal authorities remain unchanged and the key political commitments in that deal are multilateral and sequential, and have already occurred.

The new Administration will need to weigh the availability of hypothetical legal remedies against a welter of political realities on the ground. At this writing, the JCPOA seems to be working but fragile. As with the Paris Agreement, the regime of cooperation that it created has shaped the expectations of all interested stakeholders. In January 2016, Iran dismantled much of its nuclear program, in accordance with the agreement reached by the P5+1. Under the terms of the accord, the United States and the EU removed their unilateral Iran sanctions under domestic law, and the U.N. Security Council effectively lifted its economic sanctions under Resolution 2231 (while essentially leaving in place the arms embargo, travel bans, and missile transfer prohibitions that already existed). The IAEA—which like most international organizations, has a vested interest in following international law80—continues to report that Iran is in compliance with the JCPOA. Meanwhile, Iran has carefully avoided doing anything to decrease its “breakout time” toward producing a nuclear weapon, suggesting that it will not violate the deal in a significant way even while testing the accord’s limits, particularly with respect to technical provisions, perhaps to create space to negotiate with the P5+1 on further sanctions relief.

If the Iranians continue to keep their part of the bargain, legal or political, the new Administration will be hard-pressed to replace a working multilateral deal with nothing. The other partners to the deal—Europe, Russia, and China—will not default on their political obligations just because Donald Trump was elected.81 Nor will they return unilaterally to re-imposing sanctions on Iran. Meanwhile, the network of trade deals being struck between their businesses and Iran’s will likely continue to multiply. Under this umbrella of intergovernmental cooperation, Iran’s economy seems to be recovering. “Iran has made deals to expand its oil fields, build cars, and buy dozens of aircraft from the EU’s Airbus and the U.S.’s Boeing Corp. Russia is deploying anti-aircraft systems to Iran.”82 Gradual re-enmeshment of the foreign and Iranian banking sectors continues as the United States has allowed for foreign banks holding tens of billions of dollars in frozen Iranian oil revenues to repatriate those funds.83As the Obama Administration leaves office, it may well provide licenses for more American businesses to enter the Iranian market, further enmeshing Iran in transnational commercial relations. Perhaps most importantly, some in Israel have become strikingly hesitant to encourage the President-Elect to carry through on his threats to kill the deal, which has won advocates as a peaceful alternative that has “blocked Iran’s path to a nuclear weapon, and prevented the emergence of an arms race in the Middle East.”84

In theory, the new President could immediately issue executive orders to restore nuclear-related sanctions on Tehran and announce that the United States will no longer participate in any aspect of the agreement. But as government lawyers like to say, that option would be “lawful but awful.”While legally available, such an abrupt approach could be politically disastrous.If the new Republican Congress imposed new sanctions, or the new President declined to waive United States statutory sanctions in response to future Iranian actions, Iran could nevertheless choose to fulfill its JCPOA nuclear commitments anyway, to benefit from the lifting of U.N. and EU sanctions.

Conceivably, the Trump Administration could unilaterally trigger the “snapback” mechanism in the JCPOA, which allows any P-5 member to cancel the U.N. sanctions relief provided under Resolution 2231 within thirty days, by claiming a violation. But other stakeholders might not agree that such a violation had occurred. Even if the U.N. sanctions that were in place before the deal were legally re-imposed, it seems unlikely that the other Security Council members, particularly China and Russia, would enforce them. Worst of all, Iranian officials,claiming reciprocal breach by the United States, could claim just cause to deny the IAEA verification access, restart their nuclear program, and build a bomb.85 The new Administration would then have created a lose-lose situation, blowing up the preexisting deal without creating the possibility of a new one, while losing in the process its allies, its leverage, and its guaranteed visibility into the Iranian nuclear program. All of this may explain why recent reports suggest that “Trump’s advisers areputting out signalsthat rather than simply scrapping the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action . . . his [A]dministration will try to renegotiate it to get more favorable terms.”86 But that cannot happen if Iranian leaders refuse to renegotiate. For even if talks were now reopened, the new Administration is not likely to get a better deal, because the United States could not invoke as leverage the crushing multilateral sanctions that brought Iran to the table in the first place.

All of this reminds us that—as with the Paris Agreement—deals are sticky, regimes are path-dependent, and in complex political equations, the locus of domestic legal authority often plays a subsidiary role. Twenty-first century international legal engagement has increasingly expanded beyond the traditional tools of treaties and executive agreements to nonlegal understandings, layered cooperation, and diplomatic law talk—fluid conversations about evolving norms that memorialize existing understandings on paper without creating binding legal agreements. These soft law tools in turn enhance what international-relations theorists call regime-building.87 Both the Paris Climate Change Agreement and the JCPOA show how we now develop international law and institutions: less through formal devices, and more through repeated dialogues within epistemic communities of international lawyers working for diverse governments and nongovernmental institutions. This regime-building process repeatedly brings together international lawyers from many countries to talk about these issues bilaterally, plurilaterally, and multilaterally.88 And as these regimes develop, they breed a life of their own—building consensus about what set of norms, rules, principles, and decision-making procedures should apply in a particular issue area. The stakeholders first seek to define new soft norms, which, through an iterative process, gradually harden. Intricate patterns of layered public and private cooperation develop, and formal lawmaking and institutions eventually emerge. These patterns create stiff paths of least resistance from which new political leaders can deviate only at considerable cost.

At bottom, both deals exemplify high-stakes gambles that repeated participation in the transnational legal process will ultimately transform national identity.89 The Paris Agreement bet that developed and developing nations would all agree to provide progressive, cooperative national plans that would give each nation incentives to develop clean energy and enable the world collectively to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Iran Deal bet that Iran would become a more open society, enmeshed with the world, by shifting from a default of confrontation to cooperation. To make these grand gambles, like gelatin, both arrangements necessarily started soft and nonlegal, yet arguably became harder and more legal over time.

As this international lawmaking process becomes more fluid, our constitutional analysis should not become more rigid. Given that international law and institutions evolve organically, we need to develop constitutional understandings that do not operate mechanically. As we move from diplomatic dialogue to political commitments to soft regimes to shared norms to legal rules to international institutions, we should not impose a formal triptych on novel ways of negotiating international arrangements, because such rules make such arrangements nearly impossible to achieve.

Even in a Trump presidency, it is a mistake to conclude that the goal of constitutional interpretation should be to raise the costs of presidential action in foreign affairs, without regard to issue area. After all, if our constitutional readings make it harder for the President to make international deals than to go to war, that legal rigidity will inevitably shift presidential incentives to rely upon—and overextend—lethal tools of American hard power instead of deploying our diplomatic, smart power resources.In the twenty-first century, we should instead pursue more nuanced conceptual understandings of the Constitution that promote what Justice Jackson once wisely called “a workable government.”90 As Justice Stephen Breyer has recently argued, the role of constitutional interpretation must be “maintaining a workable constitutional system of government”: not simply declaring a set of formal rules, but pragmatically evaluating an existing architecture of cooperation that allows each branch of government to “build the necessary productive working relationships with other institutions . . . .”91

Most fundamentally, these case studies remind us that today, America’s observance of law—both international and constitutional—is preserved not just by the federal political branches and those officials who lead them at any particular time, but by an ongoing transnational legal process whose diverse stakeholders are not controlled by elected officials.92 As the Paris and Iran examples illustrate, these stakeholders are full-fledged, energetic actors within the transnational legal process. As the Trump Administration unfolds, these stakeholders will surely strive to use all available tools—the courts, subnational entities, media, civil society, transnational alliances and institutions, and bureaucratic stickiness—to hold America’s leaders accountable for their commitments.

Conclusion

Twenty-first century lawmaking has become “unorthodox lawmaking.”93 It is no longer limited to traditional “lawmaking,” in the sense of drafting codes and static texts. Today, it has become a process of building relationships to foster normative principles in new issue areas. This leads to “regime-building” that often crystallizes into legal norms that form a basis for a multilateral treaty negotiation. Over time, these regime-building efforts may create records of state practice that help to generate opinio juris, the notion that states engage in certain repeated practices out of a sense of legal obligation.

This transformation of international cooperation has forced a change in the role of international lawyers. Fifty years ago, government lawyers devoted their energies to drafting and concluding binding treaty language. But today, just as often, government lawyers find themselves doing the opposite. They ensure that “shalls” are changed to “shoulds,” so that commitments will be political and nonbinding, consistent with existing domestic legal authorities, and designed less to bind legally, than to build confidence, set aspirational goals, and create new default patterns of cooperation around which expectations can converge.94

As a constitutional matter, these dramatic changes in the international lawmaking process call for what Justice Breyer has termed more “pragmatic approaches to interpreting the law.”95 In a global world, Congress cannot and does not formally approve or disapprove every single act undertaken by the Executive that has external effects. As in every institutional partnership, one partner necessarily accords the other a zone of discretion—signaled by general preauthorization, consistent past practice, and the legal landscape—that allows each partner to act, while consulting closely with the other about any new commitments that will legally bind the partnership as a whole.

Whether or not you agree with the conceptual framework offered above, it is high time that we stop mechanically invoking law to choke creative mechanisms of twenty-first-century international lawmaking. Twenty-first-century international lawmaking is a living, breathing human tapestry of meetings, relationships, and personal and virtual communications, aimed at promoting and making law and regimes by deepening cooperation, engagement, and norms. To accommodate this reality, we need a legal framework that better understands the history, texture, subject matter, and substantive nature of the executive-legislative interaction surrounding particular negotiations. We live in a fast-changing multidimensional world. We should not reduce the rich mosaic of life into a rote checklist of legal tools, shoehorned into an antiquated transsubstantive triptych.

Harold Hongju Koh is the Sterling Professor of International Law at Yale Law School. He has previously served as Legal Adviser to the U.S. Department of State (2009-11), and as Assistant Secretary of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (1998-2001). An earlier version of what follows was delivered as the 2016 Vacketta-DLA Piper Lecture at the University of Illinois College of Law on October 28, 2016. He is grateful to Bill Burns, Bill Dodge, Brian Egan, Kimberly Gahan, Avril Haines, Doug Kysar, David Pozen, Todd Stern, and the members of the Yale-Duke Foreign Relations Roundtable for their helpful comments, and to Sophia Chua-Rubenfeld of Yale Law School for excellent research assistance.

Preferred Citation: Harold Hongju Koh, Triptych's End: A Better Framework To Evaluate 21st Century International Lawmaking, 126 Yale L.J. F. 338 (2017), www.yalelawjournal.com/forum/triptych’s-end.

According to the Assistant Legal Adviser of the State Department for Treaty Affairs, since 2009 the Senate has advised and consented to only eighteen treaties, less than one-third of the average approved since 1960 in any four-year presidential term. See Michael J. Mattler, Observations on Recent U.S. Practice Involving Treaties and Other International Agreements and Arrangements 2 (Oct. 15, 2016) (unpublished paper presented at 2016 Yale-Duke Foreign Relations Law Roundtable).

Louis Henkin, Foreign Affairs and the United States Constitution 217 (2d ed. 1996) (“[I]t is now widely accepted that the Congressional-Executive agreement is available for wide use, even general use, and is a complete alternative to a treaty.”); Myres S. McDougal & Asher Lans, Treaties and Congressional-Executive or Presidential Agreements: Interchangeable Instruments of National Policy: I, 54 Yale L.J. 181 (1945). See generally Oona A. Hathaway, Treaties’ End: The Past, Present, and Future of International Lawmaking in the United States, 117 Yale L.J. 1236, 1244-48 (2008) (describing “the interchangeability debate”).

Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. No. 103-465, 108 Stat. 4809, enacted Dec. 8, 1994, to implement Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, signed 15 April 1994, entered into force 1 January 1995, http://www.wto.org/English/docs_e/legal_e/04-wto.pdf [http://perma.cc/2DU3-FJB9].

Following the November 2016 election, the Obama Administration announced that it would no longer seek approval of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), at about the same time as the incoming Trump Administration declared its opposition to the deal. See Ellen Powell, What Trump’s Vow to Quit TPP Trade Deal Means for Human Rights, Christian Sci. Monitor (Nov. 22, 2016), http://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/2016/1122/What-Trump-s -vow-to-quit-TPP-trade-deal-means-for-human-rights [http://perma.cc/QQ9J-YFZD].

Cf. Karoun Demirjian & Carol Morello, State Department Gets Some Nominees, After Cruz Clears His Roadblock, Wash. Post (Feb. 12, 2016), http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/wp/2016/02/12/state-department-gets-some-nominees-after-cruz-clears-his-roadblock/ [http://perma.cc/R284-59NZ] (describing how, in the context of executive confirmations, a single Senator placed a blanket hold on all State Department nominees for several months by preventing a voice vote).

See generally Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States § 303 (Am. Law Inst. 1987) (“[T]he President, on his own authority, may make an international agreement dealing with any matter that falls within his independent powers under the Constitution.”); Henkin, supra note 4, at 219-24 (describing international agreements entered into solely by the Executive).

Agreement Respecting Naval and Air Bases (Hull-Lothian Agreement), U.S.-Gr. Brit., Sept. 2, 1940, 54 Stat. 2405; see also William R. Casto, Advising Presidents: Robert Jackson and the Destroyers for Bases Deal, 52 Am. J. Legal Hist. 1 (2012) (describing the role that President Roosevelt and his advisors played in negotiating the agreement).

See David Golove, Constitutionalism and the Non-Binding International Agreement 2 (Oct. 15, 2016) (unpublished paper presented at 2016 Yale-Duke Foreign Relations Law Roundtable,). But see id. at 9 (acknowledging that “[i]n the absence of a functioning constitutional system, President Obama rightly decided to act, in the case of [the] Iran Accord, to save the nuclear non-proliferation regime from crumbling and to avoid a potentially catastrophic war against yet another Muslim nation and, in the case of the Paris Agreement, to advance at least a modest effort to save the world from environmental catastrophe”).

See, e.g., Jack Goldsmith & Lawrence Lessig, Op-Ed, Anti-Counterfeiting Agreement Raises Constitutional Concerns, Wash. Post (Mar. 26, 2010), http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/03/25/AR2010032502403.html [http://perma.cc/F93C-MANH] (“Binding the United States to international obligations of this sort without congressional approval would raise serious constitutional questions . . . .”); Oona A. Hathaway & Amy Kapczynski, Going It Alone: The Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement as a Sole Executive Agreement, Am. Soc. Int’l L.: Insights (Aug. 24, 2011), http://www.asil.org/insights/volume/15/issue/23/going-it-alone-anti-counterfeitingtrade-agreement-sole-executive [http://perma.cc/J4ZA-BB5U]; Letter from Law Professors to Barack Obama, U.S. President 2-3 (Oct. 28, 2010), http://www.wcl.american.edu/pijip/download.cfm?downloadfile=83CE3453-EFC7-45B0-7CBA50D842A84563 [http://perma.cc/R3D4-3BZC] (“The use of a sole executive agreement for ACTA appears unconstitutional.”).

Letter from Ambassador Ron Kirk, U.S. Trade Representative, Exec. Office of the President, to Sen. Ron Wyden (Dec. 7, 2011), in The Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, supra note 21, ch. 4, § A(2) at 109-10; see also Letter from Koh, supra note 24 (finding ACTA fully consistent with existing law and not requiring any further legislation to implement).

Id. at 678. As the Court stated:

Although we have declined to conclude that [either of these two statutes] directly authorizes the President’s [actions] . . . , we cannot ignore the general tenor of Congress’ legislation in this area in trying to determine whether the President is acting alone or at least with the acceptance of Congress . . . . Congress cannot anticipate and legislate with regard to every possible action the President may find it necessary to take or every possible situation in which he might act. Such failure of Congress specifically to delegate authority does not, “especially . . . in the areas of foreign policy and national security,” imply “congressional disapproval” of action taken by the Executive. On the contrary, the enactment of legislation closely related to the question of the President’s authority in a particular case which evinces legislative intent to accord the President broad discretion may be considered to “invite” “measures on independent presidential responsibility.” At least this is so where there is no contrary indication of legislative intent and when, as here, there is a history of congressional acquiescence in conduct of the sort engaged in by the President.

Id. at 678-79 (emphasis added) (internal citations omitted).

See Koh, The National Security Constitution, supra note 23, at 139-40 (“It is hard to fault the result in Dames & Moore, given the crisis atmosphere that surrounded its decision and the national mood of support for the hostage accord . . . . [But the Court] also condoned legislative inactivity at a time that demanded interbranch dialogue and bipartisan consensus.”); see also id. at 140-41 (noting subsequent Supreme Court decisions extending Dames & Moore’s reasoning to such issues as passport revocation and regulation of travel transactions under the international emergency economic powers laws).

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579, 637 (1952) (Jackson, J., concurring). As Professor Tribe has perceptively argued, Justice Jackson’s “Youngstown Triptych” traded elegance for texture: it created a misleading “‘flatland’ constitutional universe—one constructed in a two-dimensional space, carved into three simple zones. Missing from that triptych has been an analytical guide for navigating what is in truth the multidimensional universe of relevant constitutional values and relationships.” Laurence H. Tribe, Transcending the Youngstown Triptych: A Multidimensional Reappraisal of Separation of Powers Doctrine, 126 Yale L.J. F. 86 (2016), http://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/transcending-the -youngstown-triptych [http://perma.cc/TM4Z-2Q8L].

By representing this constitutional space as a scattergraph to aid those readers who think spatially, I am decidedly not trying to substitute a rigid 2x2 matrix for the triptych. As Professor Tribe cogently notes, constitutional space is best visually depicted in three, not two, dimensions: “[T]he Youngstown framework finds no place at all for significant dimensions of the separation-of-powers picture that are orthogonal to, and often absent from, the customary two-dimensional matrix of executive versus congressional powers, including . . . the scope of prosecutorial discretion and federal power vis-à-vis the States, as well as transcendent concerns about individual rights.” Tribe, supra note 30; see also Laurence H. Tribe, The Curvature of Constitutional Space: What Lawyers Can Learn from Modern Physics, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1989) (making a similar point about the multi-dimensional character of constitutional law, using supporting research assistance from his then-student Barack Obama).

Tribe, supra note 30 (“Nothing in Youngstown, including Jackson’s classic concurrence, sets out a normative framework for deciding: (1) which kinds of presidential action in the relevant sphere are void unless plainly authorized by Congress ex ante; (2) which are valid unless plainly prohibited by Congress ex ante; and (3) which are of uncertain validity when Congress has been essentially ‘silent’ on the matter although dropping hints about its supposed ‘will.’ Nor does the canonical Jackson concurrence speak to (4) what considerations should guide the resolution of cases within this uncertain third category.”).

See, e.g., Michael Ramsey, Is the Iran Deal Unconstitutional?, Originalism Blog (July 15, 2015), http://originalismblog.typepad.com/the-originalism-blog/2015/07/is-the-iran-deal-unconstitutionalmichael-ramsey.html [http://perma.cc/U43L-CQ5H]; David A. Wirth, Is the Paris Agreement on Climate Change a Legitimate Exercise of the Executive Agreement Power?, Lawfare Blog (Aug. 29, 2016, 12:37 PM), http://www.lawfareblog.com/paris-agreement -climate-change-legitimate-exercise-executive-agreement-power [http://perma.cc/R46X-K3GF].

U.N. Conference of the Parties of the Framework Convention on Climate Change, Addendum to Part Two: Action Taken by the Conference of the Parties at Its Seventeenth Session, p. 2, U.N. Doc. FCCC/CP/2011/9/Add.1 (Mar. 15, 2012), http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2011/cop17/eng/09a01.pdf [http://perma.cc/LLV2-ZF4A].

For the full text and annexes of the JCPOA, see Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, U.S. Dep’t of State, http://www.state.gov/e/eb/tfs/spi/iran/jcpoa [http://perma.cc/7ECU -MJSV]. The Annexes include: Annex I—Nuclear Related Commitments; Annex II—Sanctions Related Commitments; Annex III—Civil Nuclear Cooperation; Annex IV—Joint Commission; and Annex V—Implementation Plan.

Some early readers of this Essay questioned whether Dames & Moore is a relevant precedent for the Iran Nuclear Deal, given that the Court there was trying to limit its analysis to the facts of that case. See supra text accompanying notes 26-27. But it seems curious indeed to suggest that the last Supreme Court precedent upholding the constitutionality of a political commitment settling complex issues with the Islamic Republic of Iran—the Algiers Accords—cannot serve as a precedent for defending the constitutionality of the JCPOA, a later political commitment settling subsequent complex issues with that very same country.

Duncan B. Hollis & Joshua J. Newcomer, “Political” Commitments and the Constitution, 49 Va. J. Int’l L. 507 (2009) (citing, inter alia, precedents in the Six-Party Talks applied to promote denuclearization in North Korea in 1994 and 2006); see also Letter from Denis McDonough, Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff, to the Honorable Bob Corker, Chairman, Senate Comm. on Foreign Relations (Mar. 14, 2015), http://big.assets.huffingtonpost.com/CokerLetter.pdf [http://perma.cc/2XBT-SZS3] (reviewing a broad range of bilateral and multilateral cooperative arrangements regarding arms control and nonproliferation that have been developed by nonbinding political commitments). Under the JCPOA, the United States did commit to propose and vote for a new Security Council resolution, which changed the nature of other countries’ legal obligations under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter to provide sanctions relief to Iran, with the possibility of “snapback” in case of Iranian default. But as noted in text, that is a subject matter area in which the U.S. Executive Branch already had considerable legal authority to adopt sanctions, and therefore to modify them under appropriate circumstances.

For an argument that the Iran Nuclear Review Act authorizes the President to enter into a legally binding JCPOA with Iran, see David Golove, Congress Just Gave the President Power To Adopt a Binding Legal Agreement with Iran, Just Security (May 14, 2015, 4:12 PM), http://www.justsecurity.org/23018/congress-gave-president-power-adopt-binding-legal -agreement-iran [http://perma.cc/9B24-7EF6].

See Marty Lederman, Congress Hasn’t Ceded Any Constitutional Authority with Respect to the Iran JCPOA, Balkinization (Aug. 8, 2015), http://balkin.blogspot.com/2015/08/congress -hasnt-ceded-any-constitutional.html [http://perma.cc/JJ4C-P7B3].

See Trump/Pence, An America First Energy Plan, Donald J. Trump for President (May 26, 2016), http://www.donaldjtrump.com/press-releases/an-america-first-energy-plan [http://perma.cc/CKB8-CF4U] (“We’re going to cancel the Paris Climate Agreement and stop all payments of U.S. tax dollars to U.N. global warming programs.”); Valerie Volcovici & Alister Doyle, Trump Looking at Fast Ways To Quit Global Climate Deal: Source, Reuters (Nov. 14, 2016, 4:49 AM),http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-climatechange -accord-idUSKBN1370JX [http://perma.cc/EK9F-WWRC].

Tim Daiss, Trump Pledges To Rip Up Iran Deal; Israelis Say Not So Fast, Forbes (Nov. 22, 2016, 1:50 AM), http://www.forbes.com/sites/timdaiss/2016/11/22/trumps-iran-deal -rhetoric-israelis-say-not-so-fast [http://perma.cc/TW84-W5EH].

Jean Chemnick, Could Trump Simply Withdraw U.S. from Paris Climate Agreement?, Sci. Am. (Nov. 10, 2016), http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/could-trump-simply-withdraw-u-s-from-paris-climate-agreement [http://perma.cc/HA7B-63YZ]; cf. Avaneeesh Pandey, Donald Trump Wants To ‘Cancel’ The Paris Climate Deal — Here’s How He Could Do It, Int’l Bus. (Nov. 9, 2016), http://www.ibtimes.com/donald-trump-wants-cancel-paris-climate -deal-heres-how-he-could-do-it-2444026 [http://perma.cc/7DK6-BSE3] (quoting Donald Trump as saying “President Obama entered the United States into the Paris Climate Accords—unilaterally, and without the permission of Congress”).

See Letter from Senate Republicans to the Leaders of Iran, N.Y. Times (Mar. 9, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/03/09/world/middleeast/document-the-letter -senate-republicans-addressed-to-the-leaders-of-iran.html [http://perma.cc/6AU7-9BC7] (“[U]nder our Constitution, while the president negotiates international agreements, Congress plays the significant role of ratifying them. In the case of a treaty, the Senate must ratify it by a two-thirds vote. A so-called congressionalexecutive agreement requires a majority vote in both the House and the Senate (which, because of procedural rules, effectively means a three-fifths vote in the Senate). Anything not approved by Congress is a mere executive agreement . . . . [W]e will consider any agreement regarding your nuclear-weapons program that is not approved by the Congress as nothing more than an executive agreement between President Obama and Ayatollah Khamenei. The next president could revoke such an executive agreement with the stroke of a pen . . . .”)

Trump Seeking Quickest Way To Quit Paris Climate Agreement, Says Report, Guardian (Nov. 13, 2016, 4:02 AM), http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/13/trump-looking-at -quickest-way-to-quit-paris-climate-agreement-says-report [http://perma.cc/S5AE -RMGQ].

Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, art. 28, Dec. 12, 2015, http://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/2016/02/20160215%2006-03%20PM/Ch_XXVII-7-d.pdf [http://perma.cc/KJK3-T3Y9].

Donald Trump’s New York Times Interview: Full Transcript, N.Y. Times (Nov. 23, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/23/us/politics/trump-new-york-times-interview -transcript.html [http://perma.cc/U2CH-8DG5].

President Clinton signed the Rome Statute just before he left office on December 31, 2000. See Clinton’s Words: “The Right Action,” N.Y. Times (Jan. 1, 2001), http://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/01/world/clinton-s-words-the-right-action.html [http://perma.cc/E3HQ-L2LK]. In May 2002, the Bush Administration purported to unsign the treaty and notified the United Nations that it did not intend to become a party to the Rome Statute. See Letter from John R. Bolton, Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, to Kofi Annan, U.N. Secretary General (May 6, 2002), http://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2002/9968.htm [http://perma.cc/4TG6-8LAV].

See, e.g., Coral Davenport, Diplomats Confront New Threat to Paris Climate Pact: Donald Trump, N.Y. Times (Nov. 18, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/19/us/politics/trump-climate-change.html [http://perma.cc/A5UE-SL5R].

444 U.S. 996 (1979) (per curiam) (dismissing on political question grounds); id. at 1006 (Brennan, J., dissenting) (citing the President’s plenary textual recognition power as a basis for affirmance on the merits); see also Kucinich v. Bush, 236 F. Supp. 2d 1 (D.D.C. 2002) (finding the question of executive authority to withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty to be a nonjusticiable political question).

See 444 U.S. 996, 996 (Powell, J., concurring) (“The Judicial Branch should not decide issues affecting the allocation of power between the President and Congress until the political branches reach a constitutional impasse.”); id. at 1006 (Brennan, J., dissenting) (citing the President’s plenary textual recognition power as a basis for affirmance on the merits).

Zivotofsky ex rel. Zivotofsky v. Clinton, 132 S. Ct. 1421, 1430 (2012) (reversing the lower court’s political question ruling on the ground that “[t]he political question poses no bar to judicial review of this case” because “[r]esolution of [plaintiff’s] claim demands careful examination of the textual, structural, and historical evidence put forward by the parties regarding the nature of the [law in question] and of the [constitutional] powers [in dispute]”). Even as a comparative law matter, as the recent British High Court opinion in the Brexit litigation demonstrates, it remains unclear whether an Executive may unilaterally, in a nonrecognition setting, withdraw a nation’s commitment from a complex multilateral treaty without legislative participation, particularly if the Executive attempts to do so in a manner inconsistent with the treaty’s terms. See R (Miller) v. Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2016] EWHC 2768 (Admin), Summary of the Judgment of the Divisional Court, Courts and Tribunals Judiciary (Nov. 3, 2016), http://www.judiciary.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/summary-r-miller-v-secretary-of-state-for-exiting-the-eu-20161103.pdf [http://perma.cc/L6P9-ZSAP] (holding that the United Kingdom Government may not rely solely on its Executive prerogative powers, but rather must seek Parliamentary approval to trigger Article 50, the withdrawal provision of the Treaty of the European Union).

461 U.S. 574 (1983). In Bob Jones, the Court followed the views of the Court-appointed amicus, not the Reagan Administration, in ruling that the First Amendment did not prohibit the Internal Revenue Service from revoking the tax-exempt status of a religious university whose practices were contrary to the compelling government public policy of eradicating racial discrimination.

See Nathan Hultman, What a Trump Presidency Means for U.S. and Global Climate Policy, Brookings Inst. (Nov. 9, 2016), http://www.brookings.edu/blog/planetpolicy/2016/11/09/what-a-trump-presidency-means-for-u-s-and-global-climate-policy [http://perma.cc/6Q8Y-DKH5] (“Trump can slow down new initiatives but would have a hard time unwinding all of the processes that have been put in place over the last nearly decade of intense work by the current [A]dministration.”)

Advancing American Energy, The White House, http://www.whitehouse.gov/energy/securing-american-energy [http://perma.cc/6GDR-HZF9] (“Since President Obama took office, the U.S. has increased solar electricity generation by more than twenty-fold, and tripled electricity production from wind power.”)

See, e.g., Adam Nagourney & Henry Fountain, California, at Forefront of Climate Fight, Won’t Back Down to Trump, N.Y. Times (Dec. 26, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/26/us/california-climate-change-jerry-brown-donald-trump.html (quoting Governor Jerry Brown as saying “We’ve got the lawyers and we’ve got the scientists and are ready to fight,” including for a legislatively mandated target of reducing carbon emissions in California to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030). States and localities could file lawsuits to hold emitters to stiffer state law standards than any federal standards that might be relaxed under the Trump EPA.

Ted Nordhaus & Jessica Lovering, Does Climate Policy Matter? Evaluating the Efficacy of Emissions Caps and Targets Around the World, Breakthrough Inst. (Nov. 28, 2016), http://thebreakthrough.org/issues/Climate-Policy/does-climate-policy-matter [http://perma.cc/8KFL-5GXC].

See Joshua Keating, What Happens If Trump Blows Up the Iran Deal?, Slate (Nov. 17, 2016), http://www.slate.com/blogs/the_slatest/2016/11/17/what_happens_if_trump_blows_up_the_iran_deal.html [http://perma.cc/2HC2-JEM2] (noting that “EU governments [recently] reaffirmed their commitment to press on with the deal” despite Trump’s election).