Who Pays? An Analysis of Fine Collection in New York City

abstract. This Essay analyzes data from New York City’s Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings on the collection of municipal fines for administrative violations in New York City. The analysis concludes that slightly more than half of fines imposed are collected in full. The Essay explores potential implications of these collection rates, as well as potential barriers to collection. The Essay concludes that well-intentioned housing and public health advocates are in a tricky situation as they seek to ensure that local public health and environmental laws are adequately enforced. Reflexively increasing resources for law enforcement and fine collection is likely to continue to enhance existing disparities in enforcement, rather than effectively target the business actors primarily responsible for public health and environmental harms. The Essay recommends that advocates focus closely on the underlying public health and environmental harms at issue, rather than push to increase resources for fine collection broadly. The essay offers several policy recommendations to this end.

Introduction

In my first month as the Healthy Housing Fellow at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, I had a small role drafting a report on the enforcement of New York City’s lead laws.1 The report evaluated enforcement of the comprehensive and ambitious lead paint laws New York City had passed in 2004.2 While childhood lead-poisoning rates have decreased since the laws were enacted, tens of thousands of children in New York City are still poisoned by lead every year. The 2004 local law envisioned robust enforcement and grappled seriously with pragmatic questions about how enforcement could be accomplished during drafting.3 However, the report found that in the rare cases when enforcement actions had been taken, the collection rate of the fines imposed on landlords who violated lead laws was less than one percent. While this number was contested by the City, the additional figures they provided only brought the collection rate up to about ten percent.4

Prompted by these findings, this Essay analyzes New York City data on the collection of municipal fines more broadly. The Essay concludes that slightly more than half of the fines adjudicated at the City’s Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings (OATH) are collected. The analysis also concludes that human respondents pay their fines at higher rates than commercial entities and identifies pervasive and at times massive write-offs in many of the more serious safety and public health-related violations.

These rates are significantly higher than those calculated in the context of lead enforcement, but they still raise a series of questions about the relationship between collection and efficacy of local laws seeking to protect the health of New Yorkers. The value of regulatory enforcement is most often viewed as a deterrent to undesirable or harmful behavior. If a punishment is rarely inflicted, the deterrent may lose its impact.5 Moreover, it is not clear that the underlying harms that trigger enforcement are ever resolved in cases where fines are never paid. Legal scholars have documented that enforcement agencies often fail to enforce consistently against commercial actors.6 However, there is often an “assumption of collection” in legal scholarship, which may contribute to an inflated understanding of the efficacy of these laws.7

The Essay concludes that well-intentioned housing and public health advocates are in a tricky situation. Reflexively increasing resources for law enforcement is likely to continue to enhance existing disparities in enforcement,8 rather than effectively target the business actors primarily responsible for public health and environmental harms. Despite our lawyerly impetus to tackle the lack of collection with ever-more-elaborate sticks, the answer actually lies in imagining a transformative approach to the public health harms that motivate advocates’ work.

Part I analyzes data from New York City’s Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings on the collection of municipal fines based on administrative violations in New York City. Part II argues that we should be interested in collection because our dominant theory of regulation relies on an effective deterrent to function and because collections failures could influence perceptions of legitimacy. Most importantly, however, Part II argues that collection failures may indicate that the underlying harms are not being addressed. Part III discusses how information and leverage function to support or undermine collection efforts in ways that can result in disparities in collection rates. Finally, Part IV recommends maintaining focus on the underlying harms even as we explore collection. It offers several policy recommendations to this end.

I. data

A. Methods

Measuring rates of enforcement is a tricky exercise.9 In theory, collections should be more straightforward. If a fine has been imposed, calculating what portion of that fine has been collected should be simple. Unfortunately, there is very rarely organized, complete data available on which fines are paid over the long-term. A 2017 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on federal collections rates noted, “There is no source of data that lists all collections of specific fees, fines, and penalties at a government-wide or agency level.”10 The same seems to be true generally at the state and city level, and is certainly true in New York City. The GAO report notes that while some federal agencies do make some collections data available, “these data are dispersed by agency, are not comprehensive, and cannot be aggregated to create government-wide data because they vary in format and in the level of detail presented.”11 Even where collection data are available, it often identifies only the dollar amount of fines collected and not the initial amount imposed, making it impossible to calculate the actual rate of collection.12

For this analysis, I used one of the rare publicly available datasets that does combine both the amount of the fines issues and the amount paid, supplemented with New York City audit reports and conversations with agency employees. I used a dataset called “OATH Hearing Division Case Status,” available on the NYC Open Data website.13 This dataset reports information about administrative hearings at the OATH, identifying, for example, the underlying violation and issuing agency, the penalty imposed, the amount paid, and the balance due. Each row in the dataset represents a summons to appear for civil penalties. OATH holds hearings for all municipal summonses, with the exception of parking tickets, which are filed at the Department of Finance’s Parking Violations Bureau.

This set reflects a subset of violations—those where respondents choose to contest their summons or are required to appear at OATH hearings. It does not include cases where people immediately pay their ticket or are not required to appear for a hearing. Respondents are served immediately with the hearing decision, “either personally or by mail” at the close of the hearing.14 Any penalties imposed must be paid “within thirty (30) days of the date of the decision, or thirty-five (35) days if the decision was mailed,” barring a stipulated agreement between the respondent and the agency.15

The OATH Hearings Division covers a range of cases related to health, restaurants, the Environmental Control Board, and taxi/vehicle-for-hire violations.16 As the adjudicatory body, OATH is not itself responsible for collecting fines. Payment is typically due to the agency that issued the initial summons. However, following the OATH hearing, the agency that issued the initial violation can upload values including “Amount Paid” into OATH’s system to update the case information as fines are paid off.17 OATH, in turn, updates the Open Dataset almost nightly.18 Ultimately, the values that are most seriously implicated in this analysis are precisely those values reported by the issuing agencies, since they reflect collections, rather than just the preliminary data from the hearing. Outstanding unpaid fines can eventually be forwarded to the Department of Finance, which is charged with collecting a wide range of unpaid debt, from parking tickets to fines for emergency repairs of residential buildings.19

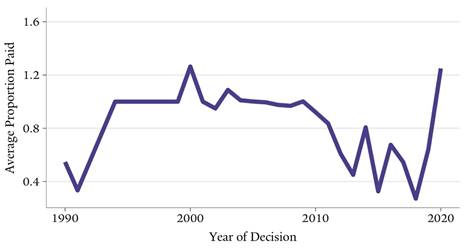

Before calculating collection rates, I narrowed the data to an eight-year time period (January 1, 2004 and January 1, 2012). I selected an eight-year range because the City can only attempt to collect a given fine for eight years.20 While I wanted a relatively recent dataset, I also wanted to allow the City the full eight years to have collected the fines in question. (Figure 1 shows the proportion of the penalties imposed paid by year. The plot shows that generally, larger proportions of older fines have been collected than newer fines. This would seem to make sense, given that fine collection can take years when the fines aren’t paid promptly, and the City has had more time to collect on older fines than new ones.)

FIGURE 1. Average Proportion of Fine Paid, 1990-2020

|

I also removed any cases where the Hearing Result was “Withdrawn,” “Dismissed,” or some version thereof. While analyzing cases that have been dismissed provides interesting information about the adjudicatory process, it is not relevant to collection rates. It was necessary to affirmatively remove these cases because there were instances where a Penalty Imposed or Amount Paid was reported, but the case itself had been dismissed. This might occur when the agency that issues the violation reports the value of the fine associated with the violation, but the violation itself is thrown out in the OATH hearing.

A brief word is in order about write-offs. In a narrow sense, penalties that are completely written off are not relevant to this analysis, much in the same way that dismissed cases are not relevant. However, write-offs are often used by agencies strategically to extract some (rather than no) payment or simply to coerce compliance in ongoing violations. Understanding which penalties are written off and why is certainly essential to understanding an enforcement regime.21 While fines can be partially, as well as fully, written off, in this dataset, 96% of cases that had a status of “Written Off” had either no value entered for amount paid (57%) or zero dollars paid (39%). Therefore, I understood the “written off” status to indicate that penalties were written off in full. Accordingly, I did not include them in my analysis. After narrowing the data in my date range by “Hearing Status” and “Hearing Result,” my subset contained 2,151,201 cases which made up 36% of the total data for my date range (indicating that about 64% of OATH violations during this period were either dismissed or written off).

Before calculating collection rates, I also had to consider inconsistencies in reporting practices. While agencies can update the data in OATH’s system, this doesn’t mean that they always do. Reporting across agencies and the underlying code sections varies but certain variables are consistently underreported, including Balance Due. Ultimately, however, the two values most relevant to this analysis, Amount Paid and Penalty Imposed, were reported at consistently high rates across the whole dataset (at 75% and 91% respectively).

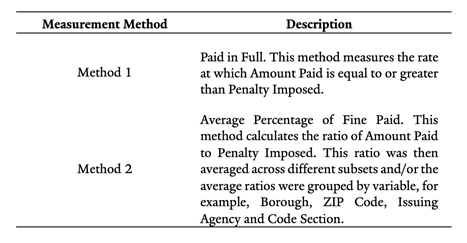

I used two primary methods to calculate rates of collection. First, I calculated the percentage of cases in a given subset where the penalty imposed was fully paid. Second, I calculated the dollar amount paid over the dollar amount of the penalty imposed. This gave me a percentage of each fine that was collected. I averaged these values to find the average percentage collected for different subsets.

B. Analysis

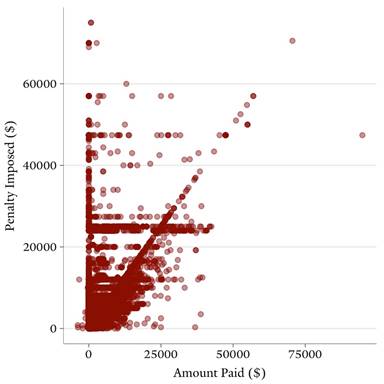

Slightly over half of the cases in the surveyed date range were paid in full.22 While still far from full collection, this is a significantly higher rate of collection than that calculated by the lead report. Accordingly, I spent much of my analysis exploring the fines were not paid in full. On average, of the 34% of fines that were not fully paid off, respondents paid an average of 26% of the value of the penalty imposed. Fines that are paid in full also tend to be for smaller sums, with an average penalty of $451, while fines that are not fully paid are an average of $1,013 and have an average outstanding balance of $824. Respondents that pay their fines in full are reflected in the diagonal line bisecting the plot—where the amount paid exactly matches the penalty imposed. The horizontal lines reflect common penalty amounts. This plot also reflects a surprising finding: the frequency of overpayment, apparent in the cluster of values beneath the diagonal line that marks full payment.

FIGURE 2. Amount Paid Versus Penalty Imposed

|

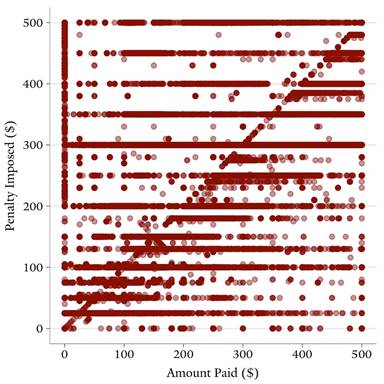

The overpayment dynamic is especially apparent in more detailed plots, like Figure 3. Exploring overpayments is an interesting area for future analysis. However, overpayments should also be contextualized in the presence of apparent write-offs. Aside from cases with a formal status of “Written Off,” frequently, the proportion of the penalty imposed to the scheduled fine amount associated with the violation was inconsistent. In the most extreme cases, scheduled violations measured upwards of tens of thousands of dollars, but the ultimate penalty imposed was only several hundred. In these cases, if the respondent paid several thousand dollars, it was registered as a substantial overpayment, even though the payment was still a small fraction of the scheduled violation amount. In terms of dollars, the mean difference between the violation amount and the penalty imposed is a massive $16,038. The median, however, is only $170, suggesting that the difference originates in a smaller number of cases where there are substantial discrepancies between the violation amount and the penalty imposed. Indeed, this difference varies dramatically by underlying code section. Because overpayments have the potential to skew rates of full collection dramatically, I ultimately coded overpayments as 100% paid, as opposed to, for example, 400% paid.

FIGURE 3. Small Fines Detail: Amount Paid Versus Penalty Imposed

|

Understanding write-offs is critical context for how collection functions. Just as low overall enforcement rates can make low collection rates more concerning, enormous write-offs where those fines are marked as paid in full may further inflate our understanding of enforcement. A similar pattern of either large write-offs or the imposition of very low penalties was described in a 2018 New York Times report on the failure of the City to effectively or consistently enforce housing laws in housing court, particularly to their full extent.23 The New York Times investigation found that “in more than two-thirds of the cases [that were analyzed], the City settled for less than 15 percent of penalties available under the law. Most were closer to 10 percent.”24 In the set as a whole, only 4% of the “Total Violation Amount,” that is, the total amount associated with the violations, was imposed.25 Despite, or perhaps in part because of, these write-offs, the city still collects a majority of the dollar amount that is imposed, at a rate of 72%.

I sought to answer two main questions in my research. First, do collection rates vary based on whether the respondent is a human being or a commercial entity? Second, do collection rates vary based on the borough or ZIP code of the underlying violation? In different ways, these questions all ask whether the relative power of the respondent impacts whether they will end up paying their fine.

1. Underlying Code Sections

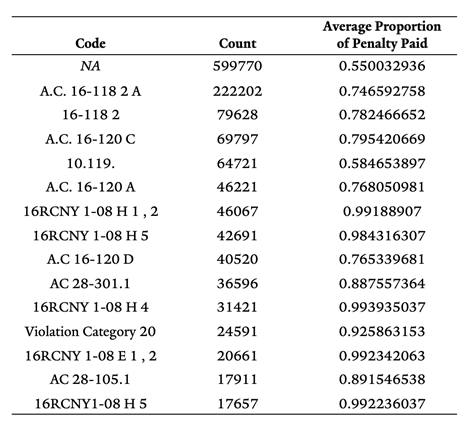

The following table shows the fifteen most common underlying code sections. Collectively, these fifteen code sections reflect a total of $507,952,262 in fines—about 39% of the total amount of penalties imposed. 55% of these penalties are paid in full and as the table indicates, 70% of the amount imposed is typically paid for these code violations.

TABLE 1. Most Common Code Sections

These code sections include violations for littering, improper recycling containers, and construction-code work-permit violations. Typographical errors and reporting inconsistencies made it difficult to make strong conclusions about code sections without explicitly coding a new subset that targeted a given code section. For example, there were several different variations of N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 16-118(2), a littering violation. Some entries used periods or parenthesis while others omitted them. Some capitalized while others did not. Some used hyphens while others used spaces, and so on.

Because of the challenges posed by these variations, I created intentional subsets for two specific code sections. I focused on N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 10-117 (unlawful defacement of property by graffiti) and N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 28-204.4 (failure to certify the correction of a violation). I chose these two because they both had a significant number of cases and are very different kinds of violations. They are not intended to be representative, instead they are intended to provide brief narrative portraits to help contextualize the data. Graffiti enforcement is closely linked to broken windows policing26 and maligned for decreasing property values. N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 28-204, on the other hand, holds property owners accountable for the past failures to resolve illegal conditions that endanger the health and safety of tenants or other people who enter or pass by their property.

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 10-117 prohibits the defacement of property—specifically writing, painting, or drawing any inscription, figure or mark, as well as affixing decals or stickers. It also prohibits the sale of aerosol paints or broad-tipped indelible markers to people under eighteen years old, or the prominent display of such paints or markers, and establishes fines for property owners’ failure to remove graffiti from their buildings in some instances. Graffiti violations are currently enforced by the Department of Sanitation. Graffiti enforcement is especially interesting at this time because there has been a resurgence of graffiti since the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York27 and graffiti has been one catalyst for confrontation with protesters in the Black Lives Matter uprisings.28

There are relatively few—1043—cases in the graffiti violation set. A substantial majority of graffiti violations occurred either in the Bronx (47%) or in Manhattan (29%). The other boroughs saw far fewer violations with only 16% in Brooklyn, 8% in Queens, and only .6% in Staten Island. This may reflect varied enforcement priorities across boroughs, given that the graffiti tracking map maintained by the Department of Sanitation does not reflect such a discrepancy in the actual painting of graffiti across the five boroughs.29

The average penalty for a 10-117 violation is $301. The average outstanding balance was $164 and the total outstanding balance was $170,927. 10-117 fines are fully collected at a rate of 41% but rates vary across boroughs. Fines for violations that occurred in Manhattan were collected in full at significantly higher rates (53%) than violations that occurred in the Bronx (15%). Fines for the small number of violations that occurred in the other three boroughs were all collected in full at rates above 70%. Overall, 10-117 cases imposed about 10% of the amount associated with the violation in penalties.30

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 28-204.4 requires certification for the correction of other violations of the New York City Construction Codes. The Construction Codes issue requirements building owners must comply with to keep buildings in safe condition. There are generally three classes of ECB violations: Class 1 (Immediately Hazardous); Class 2 (Major); and Class 3 (Lesser). After a violation has been issued, building owners have to correct the violation and certify such correction by filling out a form.31

This second violation is interesting because the respondent has allegedly already failed to comply with an order of the commissioner to correct and certify such correction of a violation. That is, it is a consequence of having failed to correct another underlying violation. We would expect that it would be especially important, from a deterrent point of view, to enforce these kinds of rules. These are the penalties that would keep those who seek to escape accountability in line.

There are 5,357 Section 28-204 cases in the set. The average penalty for these cases is $1,876 and fines are collected at a rate of 68%, slightly higher than the average rate for all code sections. The average outstanding balance was $696 and the total outstanding balance was $3,732,680. In these cases, only 6% of the total amount associated with the violations were imposed in penalties.32

2. Humans Versus Non-Human Entities

While some code violations, like summons for graffiti, publicly consuming alcohol, or littering generally implicate individuals, regulatory agencies are largely tasked with reigning in harmful conduct by industry. This is reflected in the breakdown of human versus nonhuman respondents. Humans made up 19% of the set, while non-human entities made up 79%.

I filtered the full set into two subsets approximating humans and nonhuman entities. No column in the dataset identified this information. However, I was able to construct subsets based on information in the name columns (First Name and Last Name).33 Here, nonhuman actors are overwhelmingly commercial, but may also include nonprofit organizations and churches, for example.

On average, humans paid in full at a rate of 76%, whereas nonhuman actors paid in full at only 52%. Human respondents also paid higher proportions of their fines: 85% as compared at 65% for nonhuman actors. Perhaps most strikingly, the total outstanding fines for non-human respondents was nearly twenty times as much as the total outstanding fines for human. The outstanding balance for nonhuman actors made up 91% of the total outstanding balance in the set. Even the average outstanding balance for nonhuman respondents was four times the average balance for people.

While a larger total outstanding balance is to be expected, it is not obvious why nonhuman actors pay their fines less frequently and pay lower proportions of the fines when they do pay. We might easily imagine the inverse: that commercial actors, unlike individual people, may have the money available to pay their fines and the sophistication to do it promptly in order to keep their business in compliance. Alternatively, commercial actors may have greater tools to evade payment.

3. Location of the Underlying Violation

I also calculated rates of collection based on borough and ZIP code where the underlying violation occurred. When calculating the average of the percentage paid per fine, the five boroughs were relatively consistent, ranging from 64% collection rates in Staten Island to 75% for violations that occurred in Queens. The average outstanding balance was also very similar across the boroughs, ranging from $206 in the Bronx up to $286 in Manhattan. ZIP code data showed more variation in rates.

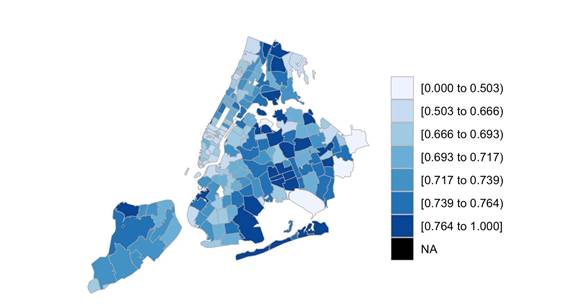

FIGURE 4. Percentage Penalty Paid by Violation Zip Code

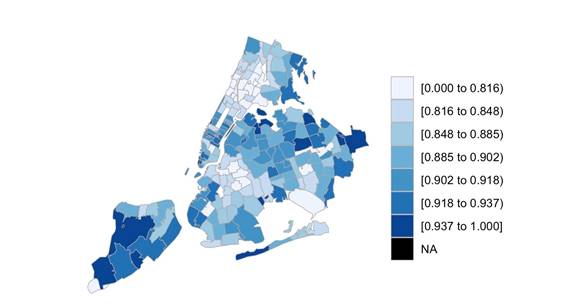

The Figure 4 ZIP code data tells us about the location of the harm (and in some cases, the person(s) harmed), but not about the location of the person or non-human actor that has done the harm. Figure 5 identifies the ZIP code associated with the address of the respondent themselves. It suggests that respondents from some Staten Island ZIP Queens ZIP codes, for example, typically pay higher proportions than respondents associated with ZIP codes in central Brooklyn and the south Bronx.

FIGURE 5. Percentage Penalty Paid by Respondent Zip Code

C. Conclusions

Overall, slightly over half of OATH fines are paid in full. Most fines are paid at least in part, but those that remain unpaid can account for thousands of dollars. Notably, the rates calculated here are higher than the City’s own reporting in some other contexts. For example, a 2018 report from the Mayor’s Special Enforcement Office found collection rates of 24% for illegal conversion fines adjudicated at OATH.34 In response to findings of the Collecting Dust report, a City spokesperson claimed that the Law Department had collected more than $194,000 in fines for lead violations.35 Combined with the $10,190 collected at OATH, this constituted a collection rate of about 10%.36 In the context of housing court penalties, the City “admitted that its collection rate for unpaid judgments was just 13 percent over a year-and-a-half period.”37

Ultimately, collection rates must be contextualized in agency practice, rates of enforcement actions, as well as an in-depth exploration of write-offs. This kind of in-depth analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, which is intended as an exploratory analysis of collection data broadly. Additionally, because this data are deeply imperfect, it forced a number of choices that may have inflated collection rates. The initial removal of cases marked as “Written Off” or “Dismissed” could have resulted in increased rates. The rates of collection do not account for reductions from the scheduled amount of a fine to the amount actually imposed, as discussed above. Additionally, different measures yielded different results. For example, measures using the Balance Due column, instead of Amount Paid, generally gave rates of collection dramatically lower. This is likely because this value was reported at much lower rates than Amount Paid.

In addition to overall rates of collection, the analysis concludes that disparities in collection rates exist based on whether a respondent is an individual person or a nonhuman (generally commercial) entities. Perhaps the most resounding conclusion of this analysis is that collection rates are often unknown to the public and sometimes to the agencies themselves, due to fragmented collections processes and inadequate data-collecting practices.38 Without a better understanding of rates of collection, it is difficult to have an accurate picture of enforcement.

II. why collection matters

We should care about collection rates for three reasons. First, the internal logic of our regulatory system requires collection in order to function. If collection does not occur when a fine has been imposed, that system may be failing on its own terms. If we hope to understand enforcement rates, we must have a sense of collection rates as well. Second, if our regulatory regime is failing to perform a key function in a meaningful way, there may be implications for the legitimacy of that regime. Lastly and most importantly, we should ask whether our regulatory regime is preventing or responding to the underlying harms regulations are designed to address if collection often occurs at low rates.

Fines have been levied for millennia, but their contemporary use in regulatory enforcement has largely emphasized a deterrence-based theory of regulation over the goals of retribution, restitution, or rehabilitation.39 This account of regulation seeks to correct for “market failures” and incentivizes desirable behavior with a regime of carrots and sticks.40 Because this account is driven by incentives—most notably by deterrence—the effectiveness of the deterrent becomes an essential indicator of a successful regulatory regime. If fines are not collected, they can’t serve deterrent purposes (nor do they serve retributive, rehabilitative, or restitutive goals).41

Ross and Pritikin’s 2009 article concluded, however, that there was an “‘assumption of collection’ underlying much of the discussion about administrative fines and penalties.”42 They argued that administrative enforcement scholarship “has essentially ignored to what extent offenders actually pay the penalties imposed against them.”43 This is reflected in the large body of literature discussing “how best to calibrate government fines and penalties to achieve optimal deterrence and other public policy goals.”44 Contemporary policy also largely assumes that once a fine is imposed, it will be collected, and media accounts of enforcement focus overwhelmingly on charges issued or penalties imposed, but rarely on the actual collection of penalties.45 Ross and Pritikin’s empirical analysis of collection rates of federal agencies concluded unambiguously that the assumption of collection is far from warranted. This disconnect should concern both scholars and advocates.

Given the tendency in enforcement literature to ignore collections data, perceptions as well as empirical measures of enforcement rates may be inflated.46 Significant scholarship highlights an existing regulatory “enforcement gap,” identifying low rates of enforcement actions in certain contexts, particularly in the areas of corporate abuse and environmental regulation.47 Both enforcement actions and collection rates must be considered together in order to understand the full impact of a given enforcement regime.

A legitimacy crisis occurs when there is a significant disconnect between public perceptions for how the government is supposed to act and how the government acts in practice.48 Perceptions of legitimacy matter in part because they can impact the future effectiveness the collection regime. If, for example, the public believes that agencies collect all fines, we may find that members of the public are more likely to pay their fines. On the other hand, like perceptions of overpolicing, perceptions of underenforcement can decrease trust in government and subjective legitimacy.49

Ross and Pritikin posit that because “neither the public, the press, nor the political branches has said much about the [collection] problem, let alone sought explanations for why it is occurring,” it is quite likely the public does not have an accurate sense of collection rates for fines.50 They also argue, however, that it would be naïve to believe that firms assume assessed penalties are collected, because that “assumes that firms will not obtain information regarding collections if it is not publicly reported. Firms, particularly those within an industry, communicate; and the attorneys who represent them are repeat players who gain knowledge and expertise regarding how an agency is likely to treat violators.”51 Unsurprisingly, much of the data and reporting on regulatory enforcement rates in fact come directly from industry law firms and consultants.52

Most of all, advocates should care about collection to the extent that lack of collection indicates a failure to prevent the underlying harms regulations are intended to address. There may be tangible harms to victims of the underlying violations if the penalties imposed are not collected. In addition to potentially failing to resolve immediate harms like unsafe food handling practice or construction that disturbs lead dust, the fact that penalties may rarely be collected in some contexts has the potential to shape business models. Sociologist Matthew Desmond’s conclusion that landlords make higher profits off of poor tenants, for example, hinges on the fact that landlord “losses remain infrequent.”53 The degree to which lack of collection implies the failure to remedy underlying harms is likely to vary by the specific context. In the case of lead paint violations, it was clear to advocates that the City’s enforcement regime wasn’t effectively addressing their clients’ serious health and safety needs. While collection should not be viewed as an end in and of itself, pervasively low rates of collection may indicate a failure to adequately protect public health and safety.

The deterrence-based regulatory theory described above reflects the rise of a philosophy of governance for which government’s proper role is correcting the fringe cases of market failure, ideally through the use of incentives rather than direct intervention. This approach aspires to a light touch but the actual task of correcting for existing market failures is not always a small one. The general trend since the “neoliberal turn” of the 1970s, with which this theory of regulation is affiliated, has in fact been one of cumulatively increasing agencies and rules.54 Arguably, the shift away from direct provisioning of services by the government and larger scale redistribution through the tax code to regulation mediated through the correction of market failures required an expansion of the mid-century regulatory apparatus, precisely because the market did not consistently produce positive outcomes by egalitarian or public health standards.55 The failure of our current system to adequately safeguard human health and safety is not a failure of regulation per se, but a failure of this particular approach to regulation, in both theory and practice.

Collection is an important piece of enforcement, and advocates should take seriously its role in a given enforcement scheme. However, as advocates grapple with low collection and other forms of underprotection, they should also proceed with caution. Regulatory underprotection is linked to overpolicing and overenforcement. An extensive body of literature shows that people of color—and in particular, Black people—are disproportionately harmed by aggressive enforcement generally, and aggressive collection practices specifically.56 Meanwhile, a recent report from the Public Rights Project concluded that the lack of adequate enforcement of corporate abuses, defined as “as illegal business activity that harms workers, consumers, tenants, and community residents,” disproportionately impacts people of color, low-income people, and women.57 A report from the African American Policy Forum highlights that Black girls, in particular, are subject to both harsher discipline and overpolicing in school, while underprotected from sexual harassment and interpersonal violence relative to white girls.58 Overpolicing can be directly linked to extralegal violence inflicted on Black populations to maintain racial order, but so too can underenforcement in some cases.59

When we view over- and underenforcement as related, and identify the ways both often consolidate existing power and precarity, it becomes more difficult to respond to failures of fine collection by simply increasing enforcement and collection resources.

III. barriers to collection

There are two primary barriers to fine collection: inability to track down the entity or person who owes the fine, and lack of leverage required to coerce payment.60 A third barrier is attempting to collect from people who simply do not have the money. This Essay assumes that collection efforts should cease in these cases. There is little deterrent value to aggressive collection against people who cannot pay, and the moral justification for action like this is dubious.61

It can be difficult to collect if the agency cannot track down the physical location and even the identity of the debtor.62 This might apply to people who live out-of-state, to corporate entities, or to others who operate without a permanent address, for example.63 Limited liability corporations (LLCs), in particular, can be harder for agencies to pin down. A recent New York statewide investigation into housing code enforcement found substantial “[d]ifficulties associated with properties owned by LLCs,” in addition to a range of other challenges facing housing code enforcement agents.64 In the report’s section on unpaid fines, the authors concluded that “[m]unicipalities struggle to identify who to collect from, especially in situations of LLC-owned or abandoned buildings.”65

In addition to being hard to track down, commercial entities can disappear. A Harvard Law Review piece exploring the puzzling concept of “ability-to-pay” tests for corporations acknowledges that “flirt[ing] with illiquidity” is a not an uncommon strategy for corporations facing fines.66 The piece notes that “[i]mportantly, these are strategic decisions. A company aware that a fine is imminent could artificially reduce the size of a fine that could be successfully challenged under the Excessive Fines Clause,” “in which case a fine might push it into insolvency, bankruptcy, and dissolution.”67 Some corporate action is even more brazen, such as that of LLCs in New York that simply dissolve when faced with wage-theft fines, only to pop back up under a different name several months later.68

The second barrier concerns whether the agency has adequate leverage to coerce payment. As argued in a 2003 Independent Budget Office Report: “[T]he ability to effectively deny a violator something of value for failure to pay a penalty (or correct a violation) is an important dimension of effective enforcement and fine collection.”69 Power and coercion are very context dependent. People, of course, can be coerced in ways that nonhuman entities cannot. Humans, for example, care about voting, about their physical liberty, and about their ability to drive. Agencies can disenfranchise, incarcerate, or suspend the drivers’ licenses of people who do not pay.70 Each of these measures is used currently in at least some states. Each of these practices is also antiegalitarian or antidemocratic and should be ended, as many advocates have argued. But these practices help us see, as a descriptive matter, how leverage can be applied to coerce payment. While permitting and licensing schemes sometimes exist in the regulation of industry, it is not clear that this kind of coercion can ever be as powerful against a nonhuman entity as it can against an individual person. Limited liability laws are designed precisely to shield commercial actors from liability and to minimize the kinds of leverage that can be wielded against them.

If a given agency does not have leverage over debtors, it may be able to coordinate with another agency that does. One method is to add unpaid fines directly to tax bills or to collect fines by intercepting tax refunds.71 The former allows cities to then leverage payment with the threat of a tax lien sales, which NYC officials see as one of the strongest tools available to coerce payment, as described above. The tax lien sale program in NYC was originally developed to coerce delinquent property owners to pay their taxes, but advocates have pushed to expand it to cover delinquent city fines as well.72 At the state level, a 2019 New York report on housing-code enforcement recommended treating unpaid fines as delinquent taxes and imposing tax liens on the real property throughout the state, in addition to the existing New York City program.73

But both the interception of tax refunds and lien sales have downsides. The application of lien sales is an instructive example of how enforcement efforts often disproportionately harm marginalized communities. Tax lien sales are linked specifically to a long history of Black land loss. Black property has often been subject to illegal property tax assessments and inflated property-tax bills.74 This disproportionately increases tax burdens, making it more difficult to pay. The tax lien sale functions the finishing blow, not the sole source of the problem. While linking unpaid fines to tax lien sales in specific cases does not necessarily condone broad increases in the use of lien sales, advocates have long pushed for moratoriums on tax lien sales, given this history.

Moreover, it is not clear that the use of lien sales is a reliable tool to coerce compliance from exploitative property owners.75 It has certainly occurred at times—the City’s Tax Lien Sale report explains that “in 2011, the first year that [Emergency Repair Program (ERP)] charges were a trigger for the lien sale, the City recouped $10 million of the $12 million in ERP stand-alone charges that were open at the time.”76 In contrast, however, sociologist and housing expert Matthew Desmond writes that in Milwaukee, landlords often simply abandon residential units as a cost of doing business if it comes to a lien sale. After they have made as much profit as they can, they leave their municipal fines unpaid and move on to the next property.77 Even if tax lien sales were fairly applied, the lien sale is structurally more effective leverage to coerce payment from individual people who live in the homes being foreclosed on than it is against landlords who own dozens of properties.

Leverage is also reflected in perceived power. More knowledgeable and better organized respondents are more easily able to counter agency attempts to coerce payments. Even if an individual will not actually be jailed, an agency’s leverage remains if the individual believes they will be jailed for failure to pay. Some enforcers rely on this information gap to coerce payment. Take, for example, the Georgia judge who explained to the New York Times that he explicitly lied to defendants about jailing them if they did not pay their fines immediately. He explained, “If they do not come up with any money, they’re released. It’s my way of determining whether they can pay or not.”78 While deception may work to coerce payments from individuals, it is unlikely to work for industry.

Shaping perception of City leverage is the fact that, in New York State, the clock is ticking down from the moment a fine is imposed until the statutory eight-year limit for fine collection elapses. While regular people likely are not trying to run down the clock for eight years, the Director of Intergovernmental Affairs at the Department of Finance argued in 2018 that “savvy building developers here throughout the five boroughs know that after eight years, when the statute of limitation expires, we can’t take action.”79 Industry and other repeat offenders may also be more likely to know of and take advantage of reduction and amnesty programs. 2009 reporting on a NYC parking ticket reduction program highlighted resident responses that quite uniformly suggested that individuals didn’t know about the program.80 City officials were quoted in the piece as saying that because the program was universally available, outreach was not “as necessary.”81 The City representative also explained that if the number of people challenging tickets were to rise substantially enough to effect the “economic viability” of the program, the City could always just cancel it.82

Given the challenges listed above, agencies may simply not have enough resources to conduct collection activities in some cases. Our demands of the regulatory state may be greater than the funding we provide it. Multiple studies have showed, for example, that collection regimes are often more expensive than the fines that come in.83 In New York City, a City Law report noted that while fines generate revenue for the city, most do not generate a profit.84 Conservatives have long responded to resource limitations by weaponizing inadequate enforcement as grounds for dismantling the regulatory state. Liberals have responded by proposing mechanisms prioritizing efficiency, most notably cost-benefit-analysis. On this view, agencies should conduct analyses to determine where their collection efforts may be most effective.85 This way of problematizing regulation studiously avoids questioning the initial endowments of various actors or the legal backdrop that protects or disempowers them. Instead, it focuses on how we might most efficiently conduct regulatory activities without changing any of the background conditions.

While seeking greater efficiency in enforcement may seem like a neutral benefit, given the leverage asymmetries laid out above, this kind of efficiency analysis can result in enforcement efforts that disproportionately deemphasize collection efforts against more powerful actors. That is, it may well be more efficient to aggressively collect parking tickets than to make Chase Bank or a millionaire landlord pay. And in fact, in New York City, “parking tickets are the only profitable rules being enforced by the City” and they make up most of the fine revenue the city takes in.86 Parking tickets are collected at far higher rates than other fines. In contrast, a City Law report determined that City agencies were more likely to waive fines for serious violations, in order to promote prompt correction.87 Violators have more leverage to have their fines waived if they cause more harm because such hazards must be promptly corrected. Similarly, at the federal level, agencies are explicitly allowed to forgo collection if the costs of collection exceed the costs of the debt or if they are facing dubious litigation prospects.88 While an efficiency-driven approach typically would not target the poorest residents, since they cannot afford to pay their fines at all, it would likely inflate collection efforts against middle class individuals and deemphasize collection efforts against the rich and commercial entities.89 A similar dynamic plays out in tax audits—the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audited the working poor and the top 1% at more or less the same rates in 2018, specifically because it was “the most efficient use of available IRS examination resources” given that auditing the rich is complicated and resource-intensive.90

This efficiency analysis also seeps into agency culture. The collection paradigm of NYC’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), for example, has been described by others and the agency itself as more “corrective” than punitive.91 HPD’s priority is forcing landlords to remedy deficiencies, not to impose or collect fines. This cooperative approach is not uncommon and would seem to make sense to the extent that it improves public health by actually resulting in more corrections of the underlying deficiencies.92 However, to the extent that repeat offenders act with impunity because they know fines will not be collected, this orientation seems problematic. We should note how far this theory of enforcement has drifted from traditional theories of deterrence and retribution. Here, landlords are never punished for their wrongdoings and their behavior is unlikely to change in the future, because of lax enforcement norms.

The lack of resources agencies have to collect fines is relative to the size of the task that agencies have been assigned. Proposing reforms to collection regimes that apply ever-smarter cost-benefit analysis without moving to redistribute power more broadly is not likely to significantly address the underlying harms. Past efforts to reform collection at the federal level have not been a resounding success. Ross and Pritikin noted in 2011 that thoughtful reforms have been ignored by federal agencies for decades. They describe “intransigent” agencies, “dismissive attitudes,” and widespread rejection the conclusions of audit report after audit report on necessary improvements to collection practices.93 Attempts to reform enforcement efforts have also consolidated existing disadvantage at times.94 This should give current advocates pause, as they approach the problem of undercollection and its relationship to underprotection today.

IV. recommendations

There are a range of discrete reforms legal advocates can explore in order to improve collection’s deterrence function in the cases they work on, including:

- Consider licensing regimes for commercial actors: Advocates should consider ex ante solutions, like licensing, in certain cases. Developing ex ante regulatory schemes like licensure could help facilitate payment, since a license could be rescinded if a fine was not paid.95 Currently, we use existing licensing schemes against poor people via the suspension of driver’s licenses. This has been a target of fines and fees advocates because it can result in the criminalization of a failure to pay when people are inevitably forced to drive with a suspended license.96 However, the general structure could be applied to nonhuman entities. There have been calls in recent years to institute licensure schemes for landlords, for example.97 Such schemes exist already in other cities and states.98 More moderate landlord licensing schemes exist as well, like New Haven’s licensing for repeat offenders.99 In New York City, Local Law 160 of 2017 mandated that the Department of Buildings no longer issues permits and revoke existing permits for landlords who have upwards of $25,000 in “covered arrears,” which includes outstanding fines entered by OATH.100

- Limit the privileges of LLCs: Advocates should support efforts to increase transparency of LLCs. One example is a new New York State law intended to increase transparency. New York City buyers will not be affected by the new law because they are already subject to rules implemented in 2015, requiring “that all members of a multiple member Limited Liability Corporation (LLC) involved in a real estate transaction provide identifying information.”103

- Accessible collection data: This analysis adds to a chorus of voices pointing to a lack of accessible data on collection rates at the city, state, and federal level.104 Agencies themselves may not always know their own rates of collection, given the fragmented collections process.105 Advocates should demand accessible and transparent collection and enforcement data. While many public interest lawyers and other advocates are confronted daily with anecdotal evidence about the failures (and at times, successes) of our enforcement regimes, data that allow us to see broader patterns is an important piece of understanding what is working and what is not. This can serve as an important basis for calls for broader scale reform. Moreover, Open Data has the potential to help grassroots organizers and individual people empower themselves to call for changes, rather than rely on professional advocates to submit and litigate requests under open records laws.106

Revoking a person or an LLC’s license to profit off of someone else’s basic need for shelter is fundamentally different than revoking the license required for individual mobility, not least because the individual can be incarcerated as a result and the LLC cannot.101 Additional collateral consequences also apply disproportionately to people in a way they do not apply to nonhuman entities. Whereas damaged credit scores can make it difficult for individuals to find shelter, make it possible for them to lose public benefits, and in some states, effectively disenfranchise individuals with laws that require them to pay criminal-justice debt before they can regain eligibility to vote after a conviction, these consequences do not similarly affect nonhuman entities.102

Ultimately, however, an exclusive focus on strengthening fine collection as an end in itself risks losing track of the underlying harms regulation is intended to address.107 It is the role of public interest lawyers not simply to accept the current regime as a given, but to follow the guidance of transformative leaders to reimagine more powerful strategies to address these harms and to use our legal toolkits to put these strategies into action. This paper cannot provide a broad roadmap—the issue it identifies is general and the solutions may be particular. But taking the original impetus for this paper as an example—the inability of both tenants and city agencies to enforce lead protections that landlords knowingly flouted, at the expense of their tenants who were lead-poisoned—advocates might ask how to help build tenant power relative to landlords directly. Increasing tenant leverage would make it easier for tenants to negotiate compliance before any enforcement action and potentially make it easier for the agency to enforce after a violation.

These kinds of moves require bold action at the state and federal level. But local reforms have a role to play as well. Advocates might also support demands to shift resources in the City budget away from the police and towards agencies tasked with protecting public health, like the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Smaller-scale demands might include active support for tenants’ unions from the Department of Housing Preservation and Development through an outreach program. Such a program could facilitate workshops for tenants on how to organize their buildings, provides educational documents for tenants about the benefits of forming tenants’ union, and establish a help line for tenants with questions about how go about organizing while staying safe from retaliation. HPD should also automatically aggregate complaints against landlords in a publicly available database, sifting through multiple properties and LLCs. While complaints and violations are currently available on HPD’s and the Department of Building’s websites, they cannot be searched by landlord names or management companies, which prevents cross-building organizing to hold landlords accountable. Private organizations have already started to fill this gap.108

This analysis of New York City collections data seeks to bring attention to the role of collection in regulatory enforcement. Collection is an important part of any evaluation of regulatory efficacy. However, it should not be viewed as an end in itself. Instead, advocates should seek information and accountability on collection and use collection data as a tool for more transformative demands.

I am very grateful to Ihab Mikati, without whom this project never would have gotten off the ground, and to Katie McConnell, without whom it never would have been finished. I also owe a heartfelt thank you to Isra Syed and Jacob Cañas for sharing their perspectives and feedback. A huge thank you to Joseph Daval and to Lawrence Liu for their encouragement and flexibility throughout the editing process. And, of course, I am grateful to Rachel Spector at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest and to the drafters of the Collecting Dust report for inspiring these questions.

Appendix

FIGURE 6. Keyword Search Used for Non-Human Set

“REALTY | CORP | INC | REST | SERVICES | PROPERTY | ASSOC | CONSTRUCT | CONDO | LP | MANAGEMENT | MGMT | HOSP | OWNER | NEWYORK | HOUSING | DEVELOP | SCHOOL | MINISTRIES | MARKET | RENTAL | HOUSING | GROUP | PARTY | CO | RLTY | PIZZA | LTD | BROOKLYN | CAR | WORLD | AMERICA | UNIVERSAL | HOME | DESIGN | BANK | HOUSE | AUTO | EQUITIES | FRIENDS | EVENTS | BUILDING | PLUMBING | STUDIO | PHOTO | CITY | SPORTS | HEADQUARTERS | ESTATE | FUND | THEATER | LADY | CHURCH | EMPLOY | SUPERMRKT | SUPERMARKET | ENTERTAINMENT | INSTITUTE | AVENUE | FRIENDS | TEAM | CENTER | CLUB | JUNK | USA | SOCIETY | GLOBAL | RENT | ROOM | BUREAU | KITCHEN | SHOP | REALESTATE | THEATRE | CARE | WORK | BAR | CASH | ZONE | REPAIRS | STREET | LLC | SERVICE”

TABLE 2. Collection-Rate Measures109

Collecting Dust: How NYC is Failing to Penalize Landlords for Exposing Tenants to Lead Dust, N.Y. Laws. Pub. Int. et al. (Nov. 13, 2019), https://nylpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/CollectingDust_WhitePaper_091219.pdf [https://perma.cc/JD7X-CNAX].

The Act “established as its goal the elimination of childhood lead poisoning by the year 2010.” N.Y.C., N.Y. Admin. Code § 27-2056.1. However, since the City Council knew that it was not feasible to inspect and remediate all lead paint in the city, it took a narrow approach that relied on landlord self-inspection, safe work practices when lead-based paint might be disturbed, and abatement upon turnover.

City officials explained that they had added a new collection mechanism via the City Law Department that was not accounted for in the publicly available data or the Freedom of Information Law requests that provided data for the report. Sydney Pereira, Landlords Rarely Punished for Lead Dust Violations: Study, Patch (Nov. 13, 2019, 10:27 AM ET), https://patch.com/new-york/east-village/landlords-rarely-punished-lead-dust-violations-study [https://perma.cc/4MXA-LN6R] (arguing that $194,000 was unaccounted for).

Ezra Ross & Martin Pritikin, The Collection Gap: Underenforcement of Corporate and White-Collar Fines and Penalties, 29 Yale L. & Pol’y Rev. 453, 479 (2011) (noting that “government auditors and many agencies ostensibly agree that non-collection of fines does not promote deterrence, punishment, compensation, or revenue generation,” the primary purposes of collection).

See Monica Bell, Hidden Laws of the Time of Ferguson, 132 Harv. L. Rev. F. 1 (2018); Michael W. Sances & Hye Young You, Who Pays for Government? Descriptive Representation and Exploitative Revenue Sources, 79 J. Pol. 1090 (2017); Criminalization of Poverty as a Driver of Poverty in the United States, Hum. Rts. Watch (Oct. 4, 2017), https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/10/04/criminalization-poverty-driver-poverty-united-states [https://perma.cc/VGQ7-XRGM]; Paying More for Being Poor: Bias and Disparity in California’s Traffic Court System, Law. Comm. C.R. S.F. Bay Area (May 2017), https://lccr.com/wp-content/uploads/LCCR-Report-Paying-More-for-Being-Poor-May-2017.pdf [https://perma.cc/92HR-MDWM]; A Pound of Flesh: The Criminalization of Private Debt, Am. C.L. Union (2018), https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/022318-debtreport_0.pdf [https://perma.cc/G7FE-SYRP]; Targeted Fines and Fees Against Communities of Color, U.S. Comm’n on C.R. (Sept. 2017), https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2017/Statutory_Enforcement_Report2017.pdf [https://perma.cc/5GR3-P62W].

See Alexandra Natapoff, Underenforcement, 75 Fordham L. Rev. 1715, 1719 (discussing the “practical difficulty with obtaining direct evidence of nonenforcement”); see also, Ross & Pritikin, supra note 5; Emily Shaw, Where Local Governments Are Paying the Bills with Police Fines, Sunlight Found. (Sept. 26, 2016, 12:02 PM), https://sunlightfoundation.com/2016/09/26/where-local-governments-are-paying-the-bills-with-police-fines [https://perma.cc/2J96-BH5Z] (noting that it is difficult to find and aggregate fine information).

U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-19-221, Fees, Fines, and Penalties: Better Reporting of Government-wide Data Would Increase Transparency and Facilitate Oversight (Mar. 2019); see also Confronting Criminal Justice Debt: A Guide for Policy Reform, Crim. Just. Pol’y Program Harv. L. Sch. 32 (2016) http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/Confronting-Crim-Justice-Debt-Guide-to-Policy-Reform-FINAL.pdf [https://perma.cc/T5XC-K3EF] (“Empirical data on the imposition and collection of criminal justice debt is often not collection or made publicly available. Even when it is, the data is often compiled by an array of agencies and bodies—clerks of courts, probation agencies, corrections officials, and private debt collection companies—which makes the information piecemeal and inaccessible.”).

See, e.g., Div. of Local Gov’t & Sch. Accountability, Report on the Justice Court Fund, Off. St. Comptroller (Aug. 2010), https://www.osc.state.ny.us/sites/default/files/local-government/documents/pdf/2019-02/justicecourtreport2010.pdf [https://perma.cc/J2ZQ-PNRS] (analyzing the source and destination of collected fine revenue without addressing the underlying amount imposed).

OATH Hearings Division Case Status, NYC OpenData, https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/OATH-Hearings-Division-Case-Status/jz4z-kudi [https://perma.cc/N56K-YMH2] (“The OATH Hearings Division Case Status dataset contains information about alleged public safety and quality of life violations that are filed and adjudicated through the City’s administrative law court, the NYC Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings (OATH) and provides information about the infraction charged, decision outcome, payments, amounts and fees relating to the case. The summonses listed in this dataset are issued and filed at the OATH Hearings Division by City enforcement agencies.”).

Report of the Mayor’s Office of Operations of Causes of and Correction Actions to Minimize Dismissals of Civil Penalty Violations Returnable to the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings, N.Y.C. Mayor’s Off. Operations (2016), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/operations/downloads/pdf/oath-dismissals-report-09-01-2016.pdf [https://perma.cc/5N8J-ZZS3].

What Happens if I Do Not Pay?, NYC Off. Admin. Trials & Hearings, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/oath/clerks-office/what-happens-if-i-do-not-pay.page [https://perma.cc/RU25-2DSC].

Tanay Warerkar, Landlords Owe NYC More than $1B in Fines, Curbed (Sept. 5, 2018, 10:50 AM EDT), https://ny.curbed.com/2018/9/5/17822710/nyc-buildings-fines-kushner-housing-violations [https://perma.cc/M2XR-DM3F].

A high proportion of default judgements resulted in write-offs, a result that we would not necessarily anticipate. If a respondent fails to show up at the hearing at all, it is not clear at all why their fines should be written off. In fact, typically, default judgement at OATH should result in the imposition of larger penalties. Many of the fine schedules include significantly higher penalties for default judgements. For example, while the standard penalty for “Unlawful defacement of property by graffiti” is $100, the default is $500. Public Safety Graffiti Penalty Schedule, 48 R.C.N.Y § 3-119 (2020). In Hudson River Park—which has its own fine schedule—the cost of “[u]nauthorized posting/ display of notices/ signs/ banners, etc” will rise from $50 to $200 if you default. Hudson River Park Rule Penalty Schedule, 48 R.C.N.Y § 3-113 (2020). Further research is necessary to explore why this might be happening at such high rates. Nonhuman entities were overrepresented in the write-offs, with 48.8% percent in whole systematic set and 57.7% in the write-offs. Humans were represented in the whole set at a rate of 68.3%, but only at 39.7% in the write-offs. This could indicate a number of things—perhaps most likely that certain code sections are more likely to result in write-offs, and that those code sections generally apply more to businesses. The total dollar amount written off for human respondents was, at $846,868,727, about one third of the $2,765,769,070 written off for nonhuman respondents.

For example, in 2016 and 2017, the Housing Preservation & Development sued one landlord “seven times, saying he had filed forty different certifications falsely claiming that violations had been fixed in regulated buildings. The total fines came to just $2,750—a small amount for the owner of property worth millions.” Grace Ashford, Leaks, Mold and Rats: Why New York City Goes Easy on Its Worst Landlords, N.Y. Times (Dec. 26, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/26/nyregion/nyc-housing-violations-landlords-tenants.html [https://perma.cc/68JU-2BUX].

See William J. Bratton, Broken Windows and Quality-of-Life Policing in New York City, N.Y.C. Police Dep’t (2015), http://www.nyc.gov/html/nypd/downloads/pdf/analysis_and_planning/qol.pdf [https://perma.cc/USP8-HPST].

David Gonzalez, Graffiti Is Back in Virus-Worn New York, N.Y. Times (July 8, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/08/nyregion/graffiti-nyc.html [https://perma.cc/YU7A-XLHY].

Mayor de Blasio Responds to Anti-Police Graffiti Near City Hall; ‘Graffiti Is Never Acceptable,’ CBS N.Y. (July 10, 2020), https://newyork.cbslocal.com/2020/07/10/mayor-de-blasio-responds-to-anti-police-graffiti-near-city-hall-graffiti-is-never-acceptable [https://perma.cc/MN5K-DUFC’].

DSNY Graffiti Tracking (Map), NYC OpenData, https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/DSNY-Graffiti-Tracking-Map-/v9sd-nunw [https://perma.cc/RE9F-SNCS].

AEU2: Certificate of Correction, N.Y.C. Dep’t Buildings, https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/buildings/pdf/aeu2.pdf [https://perma.cc/CC67-78SH].

To create a subset of human entities, I filtered out any cases where either first or last name was left blank. Next, I combined first and last names into one name column, and filtered out a long series of terms common to commercial entities (e.g., “INC,” “RESTAURANT,” and “REALTY”) as well as any numeric value. For the list of terms, see the Appendix. I created the nonhuman set by using an antijoin function to identify any names not in my humans list.

2018 Annual Report, N.Y.C. Off. Special Enforcement (2018), https://www1.nyc.gov/site/specialenforcement/data-reports/annual-report.page [https://perma.cc/5CXQ-GNQQ].

The report found that in 79% of OATH proceedings for Local Law 1, OATH delivered an “in violation” or “default” result. Collecting Dust, supra note 1, at 10. These results amassed $1,976,870 in penalties over 15 years, of which the report found only $10,190 had been collected. Id.; see also Anabel Sosa & Aaron Feis, NYC Fails to Punish Landlords for Lead Violations, N.Y. Post (Nov. 12, 2019, 10:26 PM), https://nypost.com/2019/11/12/nyc-ignores-99-of-lead-hazards-study [https://perma.cc/XZ79-6WS6] (same).

For example, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) “stated in its response to [New York City Independent Budget Office’s] question concerning the percentage of fines collected that ‘it is particularly difficult to determine what goes uncollected.’ IBO has been unable to independently estimate total fines and collections.” Letter from N.Y.C. Indep. Budget Office to Justin Foley, Chair, Northwest Bronx Cmty. Clergy Coal. Hous. Comm. 6 (July 10, 2000), https://ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/hpd.pdf [https://perma.cc/72E2-9G4L]. This is unsurprising given the fragmented collection system. It would be nearly impossible to estimate a collection rate with any degree of precision. See also Report of the Mayor’s Office of Operations on Causes of and Corrective Actions to Minimize Dismissals of Civil Penalty Violations Returnable to the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings, Off. Mayor N.Y.C. 3-4 (Sept. 1, 2016), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/operations/downloads/pdf/oath-dismissals-report-09-01-2016.pdf [https://perma.cc/5N8J-ZZS3] (noting that “a trend analysis cannot be made” of data from charges returnable at OATH Vehicle for Hire and Taxi Hearings and at OATH Health and Restaurant Hearings because “data tracking those charges and their dispositions are less comprehensive,” and that “OATH is in the process of developing those data.”).

See Torie Atkinson, A Fine Scheme: How Municipal Fines Become Crushing Debt in the Shadow of the New Debtors’ Prisons, 51 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 189, 192-93 (2016) (“The use of fines as criminal punishment dates back to ancient times and is recorded by the Greeks, Romans, ancient Near Easterners, and Germanic Tribes.” (citations omitted)).

Even assuming collection, many fining schemes in the United States do not serve these purposes due to the imposition of flat fees, which may have vastly different impacts based on the wealth of the respondent, as many others have argued. See, e.g., Oren Nimni, Fines and Fees Are Inherently Unjust, Current Aff. (May 9, 2017), https://www.currentaffairs.org/2017/05/fines-and-fees-are-inherently-unjust [https://perma.cc/FP84-XEZ4].

A. Mitchell Polinsky & Steven Shavell, The Theory of Public Enforcement of Law, in 1 Handbook of Law and Economics 407 (A. Mitchell Polinsky & Steven Shavell eds., 2007) (“In this section we analyze the optimal magnitude of monetary sanctions—which we call fines—assuming that enforcement is certain.”); Ross & Pritikin, supra note 5, at 455 (citing, inter alia, John E. Calfee & Richard Craswell, Some Effects of Uncertainty on Compliance with Legal Standards, 70 Va. L. Rev. 965, 995 (1984); and Amanda M. Rose, The Multienforcer Approach to Securities Fraud Deterrence: A Critical Analysis, 158 U. Pa. L. Rev. 2173 (2010)).

Ross & Pritikin, supra note 5, at 454 (citing U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-05-80, Criminal Debt: Court-Ordered Restitution Amounts Far Exceed Likely Collections for the Crime Victims in Selected Financial Fraud Cases 2 (2005)); see also Andrew Friedman, The “Collection Gap” Explained: A White-Collar Practitioner’s View, Yale L. & Pol’y Rev.: Inter Alia (Oct. 5, 2012), https://ylpr.yale.edu/inter_alia/collection-gap-explained-white-collar-practitioners-view [https://perma.cc/Q7C9-SKCM].

See David L. Markell & Robert L. Glicksman, A Holistic Look at Agency Enforcement, 93 N.C. L. Rev. 1, 5 (2014); Christen Carlson White, Regulation of Leaky Underground Fuel Tanks: An Anatomy of Regulatory Failure, 14 UCLA J. Envtl. L. & Pol’y 105, 112-13 (1996); see also Stuart Shapiro, Are We Enforcing the Regulations We Have, or Not?, Hill (Apr. 14, 2016, 10:30 AM EDT), https://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/uncategorized/276291-are-we-enforcing-the-regulations-we-have-or-not [https://perma.cc/E3BP-Y47P] (noting inflated perceptions of regulatory enforcement despite actual data).

See, e.g., Voices from the Corporate Enforcement Gap: Findings from the First National Survey of People Who Have Experienced Corporate Abuse, Pub. Rts. Project 5-7 (July 2019), https://drive.google.com/file/d/1TSrl-z5nyOuN_r1cX5sPXAxOO1MiIGO6/view [https://perma.cc/LJ4Z-L7CB]. Part of what makes low rates of collection in specific contexts, such as for lead paint violations, significant is that the rate of enforcement actions is also very low. In the case of NYC lead paint violations, for example, a 2018 report found that rates of enforcement actions for many violations were near zero. Lead Loopholes, N.Y. Lawyers for Pub. Interest 4-5 (2018), https://nylpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/LeadReport_WhitePaper_092718_LETTER.pdf [https://perma.cc/YA5M-96NS].

Government at a Glance 2013, OECD 21 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2013-en [https://perma.cc/E2HD-BDAS] (“If citizens’ expectations rise faster than the actual performance of governments, trust and satisfaction could decline. These changes in expectations may explain more of the erosion of political support than real government performance . . . . Trust in government has been identified as one of the most important foundations upon which the legitimacy and sustainability of political systems are built.” (citations omitted)).

See, e.g., Val Srinivas, Daniel Byler, Richa Wadhwani, Alok Ranjan & Vamsi Krishna, Enforcement Actions in the Banking Industry, Deloitte Ctr. for Fin. Servs. (2015), https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/bank-enforcement-actions-trends-in-banking-industry/DUP1372_EnforcementActionsBanking_120815.pdf [https://perma.cc/4TQ4-YJTK]; Recent Trends in Regulatory Enforcement Actions, Winston & Strawn LLP (Nov. 9, 2018), https://www.winston.com/images/content/1/5/v2/154393/Recent-Trends-in-Regulatory-Actions-Impacting-Banks-and-Financia.pdf [https://perma.cc/9FCW-QBZN].

While the rate of new final rules proposed annual has been decreasing since the 1970s, the cumulative size of the Code of Federal Regulations has grown steadily. After a spike in the mid-century and a sudden decrease from the mid-1970s to 1980s, the cumulative number of pages in the Federal Register has been increasing steadily since the early 1990s. Page numbers of the C.F.R. is a crude measure of regulatory magnitude, but it suggests that the simplest deregulatory story is overly simplistic. See also Kiersten Rhodes, Cong. Research Serv., R43056, Counting Regulations: An Overview of Rulemaking, Types of Federal Regulations and Pages in the Federal Register (Sept. 3, 2019); Reg Stats, Regulatory Studies Ctr., Columbian Coll. of Arts & Scis., https://regulatorystudies.columbian.gwu.edu/reg-stats [https://perma.cc/9H53-VLDZ] (last visited July 8, 2020).

See, e.g., Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman, Wealth Inequality in the United States Since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data, 131 Q.J. Econ. 519 (2016); Raj Chetty, David Grusky, Maximilian Hell, Nathaniel Hendren, Robert Manduca & Jimmy Narang, The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility Since 1940, Opportunity Insights (Dec. 2016), https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/the-fading-american-dream [https://perma.cc/F9PK-U5QF] (addressing democratic participation); Lauren Gaydosh, Robert A. Hummer, Taylor W. Hargrove, Carolyn T. Halpern, Jon M. Hussey, Eric A. Whitsel, Nancy Dole & Kathleen Mullan Harris, The Depths of Despair Among U.S. Adults Entering Midlife, 109 Am. J. Pub. Health 774 (2019) (addressing increasing deaths of despair); Gopal K. Singh, Maternal Mortality in the United States, 1935-2007, U.S. Dep’t Health and Human Services, https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf [https://perma.cc/99F8-FJN9] (describing the stalling of maternal mortality rates in the United States).

Civil Rights Div., Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department, U.S. Dep’t Just. (2015), https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachments/2015/03/04/ferguson_police_department_report.pdf [https://perma.cc/7ES3-DBG6]; Not Just a Ferguson Problem: How Courts Drive Inequality in California, Law. Committee for C.R. S.F. Bay Area et al. (2015), https://lccr.com/wp-content/uploads/Not-Just-a-Ferguson-Problem-How-Traffic-Courts-Drive-Inequality-in-California-4.8.15.pdf [https://perma.cc/CPZ4-2A7Z].

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Priscilla Ocen & Jyoti Nanda, Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced and Underprotected, Afr. Am. Pol’y F. & Ctr. for Intersectionality & Social Pol’y Stud. 1, 16, https://www.atlanticphilanthropies.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/BlackGirlsMatter_Report.pdf [https://perma.cc/KP2Y-GHVD] (noting that Black girls are suspended six times as often as white girls).

Mark Golub, Racial Capitalism and the Rule of Law, Items (Feb. 19, 2019), https://items.ssrc.org/race-capitalism/racial-capitalism-and-the-rule-of-law [https://perma.cc/4LF6-XS24].

Some also identify a lack of incentives for agency employees to collect as a barrier. These contrast this with debt collection in the private context. See Margaret H. Lemos & Max Minzner, For-Profit Public Enforcement, 127 Harv. L. Rev. 853, 854 (2014). The argument is that private actors have financial incentives to pursue debt collection because they benefit directly from the debt when paid. Agency employees, however, are typically not expected to benefit from the municipal fine they track down, though some have argued that this may not always hold true. Id. (“[P]ublic enforcers often seek large monetary awards for self-interested reasons divorced from the public interest in deterrence. The incentives are strongest when enforcement agencies are permitted to retain all or some of the proceeds of enforcement—an institutional arrangement that is common at the state level and beginning to crop up in federal law.”).

Aggressive collection against people who cannot afford to pay is tied to a long, racist history of debtor’s prisons. See e.g., Alicia Bannon, Mitali Nagrecha & Rebekah Diller, Criminal Justice Debt: A Barrier to Reentry, Brennan Ctr. for Just. 19 (2010), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/URLs_Cited/OT2015/14-1373/14-1373-3.pdf [https://perma.cc/396S-KG5S] (“In fact, beginning soon after the Civil War and continuing through the 1930s, many Southern states used criminal justice debt collection as a means of effectively re-enslaving African-Americans, allowing landowners and companies to ‘lease’ black convicts by paying off criminal justice debt that they were too poor to pay on their own.”). Adjudicators should adopt the kinds of ability-to-pay requirements or structured fine regimes for which many public interest lawyers and legal scholars advocate. On the necessity of developing ability-to-pay-requirements, see Beth A. Colgan, Graduating Economic Sanctions According to Ability to Pay, 103 Iowa L. Rev. 53 (2017); and Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, Municipal Violations, YouTube (Mar. 22, 2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UjpmT5noto.

Kadia Goba, City Agents Duck the ‘Billion Dollar Mystery,’ Bklyner (May 18, 2018, 1:47 PM), https://bklyner.com/city-agents-duck-the-billion-dollar-mystery [https://perma.cc/3ZHD-QXJK]; Sally Goldenberg, City Report Shows Challenges of Collecting Money from Fines and Tickets, Politico (Nov. 16, 2015, 6:26 AM EST), https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/city-hall/story/2015/11/city-report-shows-challenges-of-collecting-money-from-fines-and-tickets-028006 [https://perma.cc/CN93-E36Z] (“Uncollected debt has been a persistent problem for many years, as city officials have struggled to pin down mobile vendors, contractors and others who operate without permeant addresses.”).

It would also apply in cases where people move after the fact or pass away. See Scott M. Stringer, Fiscal Year 2020 Annual Report on Capital Debt and Obligations, Bureau Budget 9-10 (Dec. 2, 2019) (describing the composition of New York City’s debt), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/annual-report-on-capital-debt-and-obligations [https://perma.cc/SLA8-62EX].

Comm. on Investigations & Gov’t Operations, Final Investigative Report: Code Enforcement in New York State, N.Y. St. Senate 61 (Aug. 5, 2019), https://www.nysenate.gov/sites/default/files/article/attachment/final_investigative_report_code_enforcement_senator_skoufis_igo_committee.pdf [ https://perma.cc/EE6Y-YG7V].

Case Comment, Colorado Department of Labor & Employment v. Dami Hospitality, LLC, 133 Harv. L. Rev. 1492, 1498-99, 1498 n.68 (2020) (noting that the strategy is “practiced by several successful businesses including Amazon, which continually reinvests earnings, and Uber, which chooses to sacrifice short-term profits for long-term market share”).

For an account of challenges collecting owed wages from Limited Liability Corporations (LLCs) in the context of wage theft, see Neil deMause, Workers Await Gov’s Action to Make Wage-Theft Deadbeats Pay, City Limits (Nov. 13, 2019), https://citylimits.org/2019/11/13/workers-await-govs-action-to-make-wage-theft-deadbeats-pay [https://perma.cc/DE3Z-5F6C].

Is Everything Going to Be Fine(d)?: An Overview of New York City Fine Revenue and Collection, N.Y.C. Indep. Budget Off. 4 (May 2003), https://ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/Fines.pdf [https://perma.cc/43RR-2DBY].

See Robinson v. Purkey, 2017 WL 4418134, at 1 (M.D. Tenn. Oct. 5, 2017) (discussing the suspension of drivers licenses for unpaid traffic debt); Living in Suspension—Consequences of Driver’s License Suspension Policies, Fees & Fines Ctr. (Feb. 11, 2018), https://finesandfeesjusticecenter.org/articles/living-in-suspension-consequences-of-drivers-license-suspension-policies [https://perma.cc/2E9V-4VDZ].

Simon Davis-Cohen, Chicago Intercepts Tax Refunds to Collect Unpaid Debt, Hitting Poor Black Areas the Hardest, Block Club Chi. (May 11, 2020), https://blockclubchicago.org/2020/05/11/chicago-intercepts-tax-refunds-to-collect-unpaid-debt-hitting-poor-black-areas-the-hardest [https://perma.cc/QNP8-PJDX].

Report of the Lien Sale Task Force, N.Y.C. Gov’t (Sept. 2016), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/finance/downloads/pdf/reports/lien_sale_report/lien_sale_task_force_report.pdf [https://perma.cc/WT28-FY3P].