Early Release in International Criminal Law

abstract. Modern international tribunals have developed a presumption of unconditional early release after prisoners serve two thirds of their sentences, which decreases transparency and is generally out of line with the goals of international criminal law. I trace the development of this doctrine to a false analogy with the law of domestic parole. I then suggest an alternative approach based on prisoners’ changed circumstances and enumerate criteria for tribunals to use in future early release decisions.

author. Yale Law School, J.D. 2014; Dartmouth College, B.A. 2011. Thanks to Professor Mirjan Damaška for supervising this Note, to Alexandros Zervos, Willow Crystal, and Judge Theodor Meron for their mentorship, to Carlton Forbes, Matthew Letten, and the Notes Committee of the Yale Law Journal for their editorial advice, and to Emad Atiq and Lilai Guo for their comments on early drafts. All opinions and errors are my own.

Introduction

On October 27, 2009, Biljana Plavšić finally returned home to Belgrade.1 It was a sunny autumn afternoon, and the locals treated her to a triumphal reception as she traveled from the airport to her apartment. Plavšić wore a bright smile and a fur coat; she received hugs and kisses from passers-by along the way, escorted by the Bosnian Serb Prime Minister himself.2 She had spent the last six years in a Swedish prison.3

In 2000, Plavšić was indicted by the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for genocide, crimes against humanity, violations of the laws and customs of war, and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions.4 The Prosecutor alleged that Plavšić had masterminded a policy of racial extermination and persecution as a member of the three-person Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina.5 She had enthusiastically endorsed ethnic cleansing of Muslims and Croats, and achieved global notoriety after a 1992 photograph showed her greeting fellow war criminal Željko Ražnatović with a kiss over the dead body of a Muslim civilian.6

Plavšić garnered further fame by surrendering to the Tribunal shortly after her indictment7 and pleading guilty in 2002. Plavšić vowed: “The knowledge that I am responsible for such human suffering and for soiling the character of my people will always be with me.”8 In exchange, the Prosecutor agreed to drop all charges except persecution9 (a crime against humanity10), and Plavšić received a sentence of eleven years.11

However, in a January 2009 interview with Sweden’s Vi Magazine, Plavšić withdrew her confession and her apology. She described them as pieces of political opportunism intended solely to reduce her sentence, claiming, “I sacrificed myself. I have done nothing wrong. I pleaded guilty to crimes against humanity so I could bargain for the other charges.”12

Plavšić gave the interview in an apparent fit of pique after the Swedish authorities rejected her initial application for a pardon in December 2008.13 In the same interview, she took potshots at the Swedish Ministry of Justice, complaining that “[n]one of the other prisoners have read a single book,” and that “[y]our country has nothing to be proud of.”14 Plavšić had seemingly resigned herself to her scheduled release date in 2012—commentators noted that her evident lack of rehabilitation had hurt her chances for early release, perhaps fatally.15

But the President of the ICTY disagreed. In the decision approving Plavšić’s early release, President Patrick Robinson contended that she had exhibited “substantial evidence of rehabilitation”16 based in part on her “good behavior during the course of her incarceration.”17 He also noted her cooperation with the Prosecutor18 and, perhaps most importantly, the fact that she had already served two thirds of her sentence, the customary proportion entitling her to early release.19

Although Plavšić was only one of many criminals to be released early by the ICTY, victims’ groups and prominent politicians were particularly vehement about her case. Representatives of an association of Muslim and Croat camp victims complained that the decision had “nothing to do with justice”—that the ICTY had failed to “think about the blood of so many of our children, whom we are still digging out of mass graves.”20 Željko Komšić, one of the three members of the Bosnian Presidency, cancelled a trip to Sweden, and a group of inmates at a Bosnian prison sewed their lips shut in protest.21

Plavšić’s case starkly illustrates the controversy surrounding the ICTY’s early release policies. Its liberality was not a one-off—if anything, the Tribunal has since become even more generous. As Part I explains, convicts before the ICTY, International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT) now presumptively need only serve two thirds of their sentences.

How did this presumption come about, and how does it compare with the policies of other international tribunals? Will future courts—like the International Criminal Court (ICC)—also adopt it? Most importantly, is it defensible on theoretical grounds or as a practical necessity?

To answer these questions, this Note explains the origin of the two-thirds standard and articulates a theory of early release adapted specifically to international law. Part I explores current early release doctrine and concludes that the ad hoc tribunals operate under confused premises—specifically, that the vagueness of these tribunals’ founding documents and the absence of a consistent arbiter for early release have led to misguided modeling of international early release after domestic parole. It describes how the ICTY has promulgated an influential presumption of release at two thirds of sentence that has been mimicked by the other ad hoc tribunals, and which may soon be adopted by the ICC as well.

Part II articulates an alternative theory of early release. It begins by contrasting the goals of international and domestic criminal law. International criminal law attempts to condemn serious crimes and reconcile past enemies, while domestic law achieves reconciliation only incidentally. On the other hand, domestic policymakers aim to minimize costs and prevent recidivism, which are secondary issues for international tribunals. Widely differing objectives imply that international judges should be cautious about borrowing domestic legal practices wholesale. I argue that such borrowing has backfired in this case: automatic early release dilutes condemnation and enrages victims because of its opacity and because commutation has traditionally been associated with mitigated guilt, as I discuss below.22

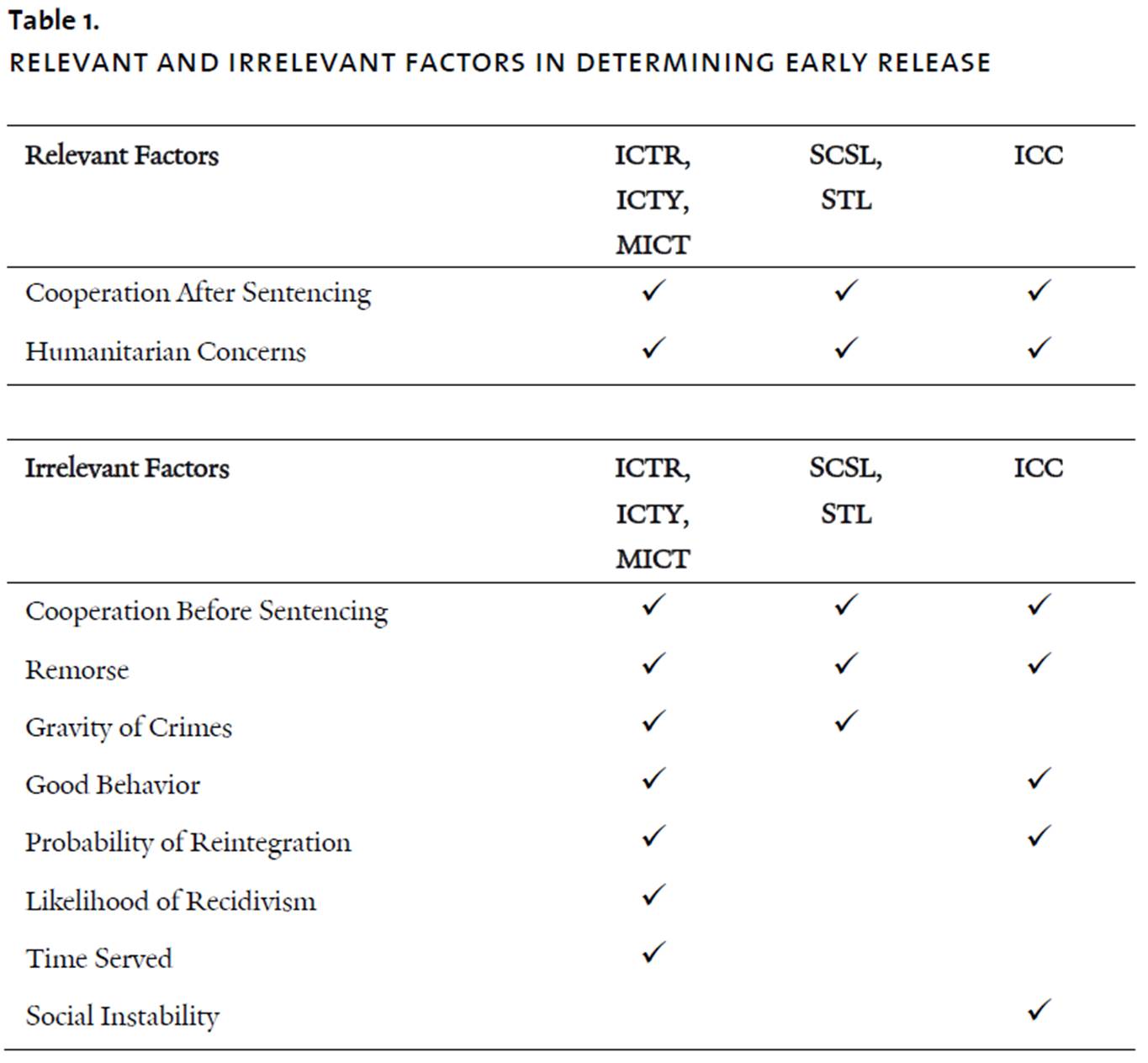

This discussion lays the foundation for my alternative approach to early release, which emphasizes changed circumstances of the prisoner. Part II separates relevant factors—fresh information casting doubt on guilt, cooperation after sentencing, and humanitarian concerns—and irrelevant factors, such as remorse (easily feigned, as in Plavšić’s case), the probability of recidivism, and the gravity of crimes committed. Above all, I suggest that courts should never grant early release by default.

This is not to say that international tribunals are too lenient or too strict in general—there is a larger debate on sentencing length in international criminal law on which I remain neutral.23 Instead, I contend that the special outrage surrounding Plavšić’s case reflects more than the usual agitation for harsher sentences. It suggests something particularly inflammatory about releasing her early, absent any real remorse or changed circumstances and based on the attitudes of a single judge. If Plavšić deserved to be released after seven years even in the absence of changed circumstances, then her original sentence ought to have been seven years. I argue that present early release doctrine does not serve the principles of international law regardless of one’s underlying normative position on the appropriate length of initial sentences.

My argument fills an important gap in the literature. Academics have written little about early release in international law, largely due to the lack of jurisprudence on the subject. Early release following the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials was almost entirely motivated by sui generis concerns of politics and fairness rather than lasting doctrinal commitments,24 and the ICTY and ICTR only commuted their first sentences in 200125 and 2011,26 respectively. A project such as this one has therefore only become viable within the past decade.

Despite the lack of scholarly attention, politicians and commentators have vigorously criticized the ad hoc tribunals for their exercise of early release powers. Complaints have grown louder as the tribunals have grown more generous in recent years. In March 2012, the Prosecutor General of Rwanda called the ICTR’s release of genocidaire Tharcisse Muvunyi “intolerable” and demanded “a genuine apology” from Muvunyi as a necessary precondition for release.27 Less than a month later, Rwandan President Paul Kagame attacked the ICTR as “a token meant to blind us and give us the impression that they are doing justice,” concealing the fact that genocidaires are released “shortly after” conviction.28 Similarly, Croatian President Ivo Josipović has suggested that early release “should be very exceptional” and that he “would never pardon certain crimes, like rape, murder and war crime.”29

So far, such criticisms have centered on the ICTR, ICTY, and MICT (collectively, the International Criminal Tribunals (ICTs)). The International Criminal Court (ICC) imposed its first sentence on July 10, 2012,30 and will likely not consider any applications for release for a number of years. The ICC has time to learn from the successes and failures of the ad hoc tribunals, and to craft its procedures accordingly.

The topic of early release is therefore ripe for consideration on three counts: the conspicuous absence of substantive analysis so far, mounting criticism by politicians and commentators, and the unique inflection point between the closing of the ad hoc tribunals and the opening of the ICC.

I. current doctrine

As the Introduction notes, modern early release doctrine originates almost exclusively in the practice of the ICTs. Prior courts used early release as a Band-Aid for judicial error rather than as a planned component of a well-functioning legal system. After the post-World War II trials at Nuremberg and Tokyo, clemency was widely granted31 in order to win over Japan and Germany as Cold War allies32 and to compensate for inconsistencies at initial sentencing.33 It was only with the arrivals in the 1990s of the modern ad hoc tribunals that early release attained a systematic character resembling its use in domestic jurisdictions.

However, as we will see, even these Tribunals have applied early release quite messily. They blur the lines between domestic clemency and parole, ultimately applying a broad mélange of criteria that has led to a much-criticized spate of releases. Most troublingly, the ICTs have adopted something like a presumption of early release for the criminals they convict, even in the absence of cooperation with the Prosecutor or demonstrated remorse.

The policies of these two tribunals will cast a long shadow over international criminal law. Future courts appear poised to borrow heavily from the doctrines set by the ICTs.34 As Parts II and IV suggest, the ICC and its contemporaries would benefit from thoughtful reconsideration of the theory underlying early release.

A. Sentencing at the ICTs

As a preliminary matter, it is important to survey sentencing practices at the ICTs. The Tribunals have much in common, including overlapping judicial benches35 and nearly identical Statutes and Rules of Procedure and Evidence.36 All three were established by the United Nations Security Council: the ICTR and ICTY were designed to address specific conflicts in Rwanda and Yugoslavia, while the MICT was intended as a successor tribunal for the other two. The MICT has taken over all new trials and enforcement matters (including early release) from the ICTR since July 2012 and for the ICTY since July 2013.37

Despite overarching similarities, the Tribunals differ somewhat in the exact substance of their early release policies. The ICTY followed a policy of early release after prisoners serve two thirds of their sentences;38 in contrast, the ICTR applied a three-quarters standard in all three of the early releases that it granted before its closing.39 The divergence stemmed from the perceived greater severity of crimes before the ICTR.40 While I argue in Part II that early release should never be presumptively granted, the ICTR briefly left some hope for future tribunals to follow its relatively restrained example.

But not for long. The President of the MICT has already granted early release in two cases, and in these cases he explicitly resolved to apply the jurisprudence of the ICTY over that of the ICTR.41 Because the MICT will decide the vast majority of ICTR applications for early release, the three-quarters rule has turned out to be merely a temporary deviation rather than a competing standard.

Thus, the remainder of my analysis focuses on early release doctrine as developed by the ICTY. Because of its breadth and its endorsement by the MICT, future tribunals will likely use it as the primary touchstone for their own practice.

B. The Statutes and the Four Factors

The ICTY seems to have implemented early release policies that are significantly more generous than its framers intended. It has adopted something like a presumption that prisoners need only serve two thirds of their sentences, apparently out of confusion between commutation and parole.

The Statutes of all three ICTs contain nearly identical language concerning early release. The Statute of the ICTY mandates:

If, pursuant to the applicable law of the State in which the convicted person is imprisoned, he or she is eligible for pardon or commutation of sentence, the State concerned shall notify the International Tribunal accordingly. The President of the International Tribunal, in consultation with the judges, shall decide the matter on the basis of the interests of justice and the general principles of law.42

The text is intentionally vague: it grants the President of the ICTY wide latitude to implement her own standards subject only to malleable “interests of justice” and “general principles of law.”

However, it is important to note at this point that the Statute only contemplates the convicted person’s eligibility for pardon or commutation of sentence, not for parole.43 This is a crucial distinction because, as we will see, domestic actors grant commutation much less often than they do parole.44 The plain language of the Statutes suggests that their framers intended early release to be similarly rare.

Much of the doctrinal movement from standards of commutation to standards of parole occurs in the Tribunals’ Rules of Procedure and Evidence, which are intended to fill the interstices of their respective Statutes.45 The Rules all lay out the same four major factors that the President must consider in her early release decisions: “the gravity of the crime or crimes for which the prisoner was convicted, the treatment of similarly-situated prisoners, the prisoner’s demonstration of rehabilitation, as well as any substantial cooperation of the prisoner with the Prosecutor.”46

Procedurally, the Rules require enforcing states to notify the President of prisoners’ eligibility for early release;47 the President must then consult “with the members of the Bureau and any permanent Judges of the sentencing Chamber who remain Judges of the Tribunal.”48 However, the ultimate decision rests with the President alone, who occasionally must overrule her colleagues when they disagree.49

While most early release decisions consider each of the four factors, the factors have acquired unexpected contours through time and use. Successive Presidents of the ICTY have interpreted the “treatment of similarly-situated prisoners” as implying the present two-thirds standard of early release. While this standard is internally consistent—as would be a one-third, or a one-quarter standard—the origins of this generous presumption demand closer examination.

Because of the importance of consistency in the execution of sentences, the “similarly-situated prisoners” factor has eclipsed the other three to become essentially dispositive in the ICTY’s early release jurisprudence. High gravity of crimes has never barred release.50 (The ICTY is understandably reluctant to label international crimes as anything but extremely grave.51) Because the gravity of crimes always weighs negatively on a petition for early release, this factor does not sharply differentiate between cases and is sometimes simply not addressed.52

Inversely, cooperation with the Prosecutor is only ever treated as a positive factor for early release. The Tribunals follow the “generally recognized international standard[]” “against self-incrimination,”53 so refusal to cooperate is never treated as a bar or even a negative factor in release decisions.54

Rehabilitation figures somewhat more prominently in early release decisions, but again it is not dispositive. While the failure of a prisoner to show remorse has occasionally sparked disagreement in the President’s consultations with her fellow judges,55 the President has nevertheless tended to release prisoners even in the absence of demonstrated remorse—or even, as in Plavšić’s case, when concrete evidence exists to the contrary.

Thus, early release in the ICTs is now dominated by the two-thirds standard. In the entire history of the ICTY, the President has only declined to release a single criminal who had passed the two-thirds mark, and even then only very reluctantly. (President Fausto Pocar denied Predrag Banović commutation based on a technicality in the French law of parole;56 Pocar was naturally concerned that this decision would cause inconsistency in enforcement, but curiously concluded that “no . . . inequity of treatment is currently being suffered by Banović.”57)

One recent case illustrates the primacy of the two-thirds cutoff. On January 9, 2013, ICTY President Theodor Meron granted early release to Mlađo Radić, who had been sentenced to twenty years in 2001 for crimes against humanity (including murder, torture, and rape) and war crimes (including murder and torture).58 Meron noted that Radić’s crimes were “of a high gravity,”59 that there was “little to no evidence of actual rehabilitation,”60 and that Radić had not cooperated with the Prosecutor of the Tribunal.61 In fact, as Meron explicitly noted, “the only factor that weigh[ed] in favour of granting the Request [was] the fact that Radić served two-thirds of his sentence.”62

There is a striking circularity involved in distilling the “similarly-situated prisoners” factor into a standard for release at two thirds. As described above, that standard would be equally satisfied by a policy that granted release at one quarter, or one tenth, or never. By disregarding the other factors and rendering this one dispositive, the President frees herself to establish whatever standards she wishes, so long as she applies them consistently between prisoners. Her only touchstone is domestic practice—and as the following Subsection argues, the ICTY has seriously erred in its interpretation of domestic law.

Given the well-publicized and controversial generosity of the ICTY’s early release practice and the potential for disagreement within the judicial ranks, have trial judges attempted to compensate with longer initial sentences? After all, unless a defendant were to receive something near the maximum sentence, a judge could deliver a sentence fifty percent longer than the one she would have preferred in the absence of the two-thirds standard. (This theoretical possibility is explored further in Section III.A.)

The ICTY Appeals Chamber rebuked the Trial Chamber for attempting exactly this in the case of Dragan Nikolić. According to the Appeals Chamber, the trial judgment “mechanically—not to say mathematically—gave effect to the possibility of an early release,” and therefore “attached too much weight to the possibility of an early release.”63 The Appeals Chamber reduced Nikolić’s sentence accordingly.64

Without the ability to compensate for two-thirds release at the trial level, the Presidents of the ICTY have effectively chopped away a third of every sentence that the Tribunal delivers. Why has this group of jurists, presumably as sensitive as anyone to the arguments of Prosecutors and the pleas of victim groups, adopted such a generous policy as a matter of course? The answer lies in the interaction between domestic and international law.

C. Confusion over Parole and Clemency

Recall that all of the ICTs’ Statutes refer to “the applicable law of the State” when—and only when—“the convicted person . . . is eligible for pardon or commutation of sentence.”65 The Rules of Procedure and Evidence of the ICTR and ICTY similarly only contemplate “pardon or commutation.”66 Pardon and commutation (or, in the other official language of the Statutes, “[g]râce et commutation de peine”)67 are terms of art specifically referring to unconditional, unsupervised release granted at the discretion of the executive.68 Nothing in the comments of the UN Secretary-General, who drafted the early release provision along with the rest of the ICTY Statute, suggests that he intended anything other than the plain and well-established meaning of commutation and pardon.69 In fact, he considered and rejected a proposal by a committee of French jurists for a system similar to parole.70 This system—called “remise de peine”—essentially mandates automatic early release for French prisoners except in cases of misconduct.71 It is worrisome that the ICTY has now adopted a system of early release so similar to the one that the drafter of the ICTY’s Statute explicitly rejected. Evidence from the drafting process indicates that a conscious choice was made for the Statute to exclusively accommodate executive clemency.

The Tribunals have partially respected this legislative intent, in that they only award unconditional release.72 However, they have deviated by focusing on domestic eligibility for parole rather than for commutation. The two-thirds presumption followed by the Tribunals stems from the policy of most enforcing states to allow prisoners to apply for parole after serving two thirds of their sentence, at the latest.73

This matters because clemency is much rarer than parole in domestic law. To see why, we will briefly consider national parole and clemency regimes in more detail.

First, parole. Virtually all jurisdictions agree that “the primary justification for parole is rehabilitation.”74 Parole provides an incentive for inmates to behave well and to participate in certain rehabilitative programs (job training and church attendance, for example);75 it also overtly rewards demonstrated rehabilitation in its criteria for early release.76

Somewhat less nobly, parole benefits the state fisc by reducing the prison population. South Africa has launched a number of “special remissions programmes” intended solely to reduce its prison population: the programmes benefited approximately 65,000 prisoners in 2005 and 2006,77 and 45,000 prisoners in 2012.78 Similarly, for much of its history, the French analog to parole (la libération conditionnelle) “was often used merely as a tool for prison officials to ameliorate administrative problems such as overcrowding or budget deficits.”79

Parole boards must be generous in order to achieve either of these goals. The more widely parole is granted, the more likely prisoners are to take its incentive effects seriously. Likewise, the more widely parole is granted, the greater the savings to the penal system. Thus in 2011, the United States had approximately 850,000 parolees,80 compared to 1.6 million prisoners,81 despite having abolished federal parole in 1984.82 Canada had 8,737 parolees, compared to 14,419 prisoners;83 and virtually all Western nations have extensive procedures governing conditional release.84

In contrast, clemency in national law is the exception rather than the rule. Only two prisoners were granted clemency in Canada during 2011, a rate more than a thousand times lower than the parole rate.85 In the United States, President Barack Obama has granted just thirty-nine presidential pardons since taking office,86 and state governors have proved similarly reluctant to pardon significant numbers of criminals.87

Clemency has historically allowed the executive to temper excessively harsh standardized punishments88 and to “perform[] a variety of important error-correcting and justice-enhancing functions”—for example, a person convicted of murder could be pardoned if the real murderer made a dying confession.89 This idea animates the modern policies of countries like Canada, which only grants clemency where there is “clear and strong evidence of an error in law, of excessive hardship and/or inequity, beyond that which could have been foreseen at the time of the conviction and sentencing.”90 In other words, clemency permits sentence adjustment based on changed circumstances. This is exactly the rationale for early release that I endorse in Part II.91

In sum, clemency and parole play very different roles in domestic law. Nevertheless, the Presidents of the ICTs have relied heavily on factors that classically appear in domestic parole hearings. The consideration of these parole factors sometimes even eclipses the four factors explicitly set out in the Tribunals’ Rules. For example, the decision granting Miroslav Kvočka early release92 paid scant attention to his “particularly grave”93 crimes or the fact that he had not cooperated with the Prosecutor,94 and entirely omitted discussion of remorse. President Meron instead emphasized Kvočka’s “prior professional integrity”95 and good behavior in prison:

Kvočka has shown good respect for management and staff and complied with the Rules of detention and instructions of the guards. At all times he has maintained cordial relations with his fellow detainees and his physical and mental health is good. Kvočka’s behaviour . . . persuades me that Kvočka has demonstrated a strong possibility of rehabilitation.96

These criteria are astonishingly similar to the criteria that parole boards usually apply,97 but not at all like those typical in pardon or commutation.98

Why have judges in the ICTs so conspicuously blurred the line between clemency and parole? Two main possibilities present themselves.

First, the standards of parole may simply be easier to implement. Because executive clemency is ad hoc and often politically motivated,99 it does not lend itself well to systematic application. Defaulting to parole may also have been the most natural way to reconcile heterogeneous domestic early release programs in enforcing states: one influential study commissioned by the ICTY equated early release to parole, likely because it would have been nearly impossible to survey clemency practice across different countries.100 Presidents relying on this study and others like it could easily have slid from commutation to parole without realizing the terminological shift.

Second, one might suspect that the Tribunals are merely echoing the liberality of the enforcing states themselves. Of course, if no nation were willing to enforce a sentence on an international criminal, the tribunal would have to release her. As a result, no court lacking its own prisons could enforce sentences longer than the maximum allowed in the most punitive enforcing state. And crucially, if a tribunal started with a set of very liberal enforcing states, it could not subsequently clamp down on early releases without disadvantaging later defendants.

Can we explain the ICTY’s generosity in these terms? As a factual matter, probably not. At any given time, at least one of the ICTY’s enforcing states has always permitted life imprisonment without even the possibility of parole. When the ICTY approved its first request for early release by Zlatko Aleksovski in 2001,101 the state holding that prisoner (Finland) permitted life sentences without possibility of parole.102 At present, five other enforcing states still sentence prisoners to life without parole.103 These domestic sentences are at least as severe as any sentence that any international tribunal has the authority to administer.104

Moreover, there is no evidence that Finland pressured the ICTY to release Aleksovski in this case, or that it objected to the continued enforcement of his sentence. (The sentence was a comparatively light seven years.105) If it did object, the appropriate time to express concern would have been at the initial negotiations to house convicts—Spain did so, for example, by refusing to enforce sentences longer than twenty years, to conform to its domestic penal policy.106

But even assuming that Finland disagreed with the ICTY so strongly as to threaten termination of enforcement rather than continuing to imprison Aleksovski, it seems oddly lazy to simply release him rather than to search for alternative arrangements. The ICTY could likely have found another state with more permissive policies, or, as a last resort, simply held him in the ICTY’s Detention Unit in The Hague.107 If many nations were this unwilling to hold a prisoner past her earliest eligibility date for parole, that would be a factor arguing for a centralized international prison system rather than for a policy of broad and automatic releases.

Given the lack of evidence suggesting reluctance to imprison, the political obstacles that nations would face in advocating for the release of international criminals, and the multitude of alternatives, it seems unlikely that the ICTY had to release prisoners simply for lack of willing hosts. More likely, the succeeding Presidents of the ICTY, saddled with the herculean task of applying disparate penal philosophies to a formless body of law, instinctively drifted toward the regularized parole procedures that they had already known to work in their home countries.

Whatever the explanation, the substitution of parole eligibility for commutation eligibility has had large practical consequences. Commutation is granted much less regularly than parole in the domestic context;108 if left to their own devices, enforcing states would virtually never recommend unconditional release. The misapplication of domestic jurisprudence is thus ultimately responsible for the creation of the two-thirds standard.

D. Looking Forward: The International Criminal Court and Other Tribunals

The ICC sentenced its first criminal, Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, on July 10, 2012;109 at the time of this writing, Lubanga’s case was still pending appeal.110 The ICC consequently has several more years before it will have to solidify its early release policy by deciding an application. Similarly, the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) sentenced its first criminal, Charles Taylor, on May 30, 2012,111 and the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) has yet to pronounce any sentences.112 None of these Tribunals is formally bound by the jurisprudence of the ICTs.113 Each therefore has the opportunity to learn from the successes and mistakes of these latter courts and adjust its early release practices accordingly.

Presently, the SCSL and STL seem happy to import the practices of the older ad hoc courts without modification. The Statutes of both Tribunals set out requirements for commutation and pardon that are functionally identical to those of the earlier ad hoc tribunals,114 as are the requirements in their Rules of Procedure and Evidence.115 The newer tribunals will probably interpret their Statutes and Rules based on the jurisprudence of their older cousins.

The ICC carves out a different path. The Rome Statute—importantly, adopted by treaty rather than by UN fiat—deviates significantly from the Statutes of the ICTs in its treatment of sentence reduction. Like those of the ad hoc tribunals, the ICC’s Statute requires that “[t]he Court alone shall have the right to decide any reduction of sentence,”116 a requirement that is corroborated by its agreements with enforcing states.117 However, its procedures for sentence review differ significantly from those of the other Tribunals. The Rome Statute mandates review “[w]hen the person has served two thirds of the sentence, or 25 years in the case of life imprisonment.”118 It also lays out a very different set of factors:

1. The early and continuing willingness of the person to cooperate with the Court in its investigations and prosecutions;

2. The voluntary assistance of the person in enabling the enforcement of the judgements and orders of the Court in other cases, and in particular providing assistance in locating assets subject to orders of fine, forfeiture or reparation which may be used for the benefit of victims; or

3. Other factors establishing a clear and significant change of circumstances sufficient to justify the reduction of sentence, as provided in the Rules of Procedure and Evidence.119

The Rules contain several further departures from the practice of the ad hoc tribunals. First, sentence reduction at the ICC is determined by a panel of three judges, rather than unilaterally by the President.120 The Rules also enumerate several additional criteria:

1. The conduct of the sentenced person while in detention, which shows a genuine dissociation from his or her crime;

2. The prospect of the resocialization and successful resettlement of the sentenced person;

3. Whether the early release of the sentenced person would give rise to significant social instability;

4. Any significant action taken by the sentenced person for the benefit of the victims as well as any impact on the victims and their families as a result of the early release;

5. Individual circumstances of the sentenced person, including a worsening state of physical or mental health or advanced age.121

Some of these factors are very reasonable, particularly the two laid out in the Rome Statute. On the other hand, a couple of the factors in the Rules—most notably “the conduct of the sentenced person while in detention” and “the prospect of . . . resocialization and successful resettlement”—have little place in early release jurisprudence. The ICC should also take care not to transform the two-thirds eligibility standard into a two-thirds presumption of release, as the ICTs have done.

Because these more problematic factors are articulated solely within the Rules and not by the Rome Statute, the ICC may still redraw them before they become entrenched by actual use. Similarly, although the SCSL and STL will be guided by the standards set by the earlier ad hoc tribunals, they too would benefit from careful analysis of their criteria, as I lay out in the following Part.

II. a theory of early release in international law

Early release is most useful as a means to respond to changed circumstances. When new information comes to light casting doubt on the defendant’s guilt;122 when the defendant provides assistance to the Prosecutor that had not been accounted for at trial;123 when the tribunal is unable to provide adequate care for sick or elderly prisoners124—in these cases, early release allows the tribunal to adjust sentences in the interests of justice.

But there is no reason why unconditional early release should be granted as a matter of course. If the ICTY feels that a defendant deserves twenty years in prison, it should sentence her to twenty years—not sentence her to thirty years and then release her after two thirds of that time. The latter policy shortens the maximum term available to the Tribunal in probable violation of the intent of its founders. It also makes international criminal law more confusing to observers and angers victims groups, who do not understand why the Tribunal opts to release prisoners early despite lack of remorse for their crimes.

This Note thus makes an appeal to readers regardless of whether they believe that overall sentences are too harsh or lenient. Perhaps Mlađo Radić deserved to have spent only thirteen years in prison, and early release at thirteen years was a fairer outcome than having him serve the twenty years to which he was originally sentenced. In such a case, the fairest and most transparent policy would have been to initially sentence him to thirteen years. And if the President’s assessment of just deserts differs from that of the trial and appeals chambers, it is difficult to argue that her judgment should substitute for theirs.

Unfortunately, the ICTs have made no attempt to separate pre- and post-sentencing factors. For example, the President of the ICTY has held guilty pleas to constitute remorse for the purposes of the Tribunal’s four factors,125 despite the fact that the guilty pleas had already resulted in substantial sentence reductions.126

In this Part, I distinguish factors that ought and ought not to figure into early release decisions (“relevant” and “irrelevant” factors, respectively). A key commonality among the relevant factors is that they involve changed circumstances—tribunals should act only upon new information that was not available at trial.

A. The Goals of International Criminal Law

As a prelude to analysis of early release factors, we should consider the underlying goals of international criminal law. In particular, we should consider the ways in which those goals differ from the goals of domestic criminal law, and by implication the ways in which international early release should differ from domestic parole. Commentators do not uniformly agree on the aims of international justice; nevertheless, I will briefly summarize the attitudes of the tribunals’ founders as well as the current scholarly conversation.

The four most popularly accepted purposes of international criminal law are deterrence, retribution, expressive condemnation, and reconciliation. The first two, deterrence and retribution, have particularly stood out in the historical record. From the Nuremberg Trials127 to the establishment of the ICC,128 commentators have emphasized the ability of international law to prevent future crimes and satisfy the demands of justice.129 The ICTY has observed that it and the ICTR “have consistently pointed out that two of the main purposes of sentencing . . . are deterrence and retribution.”130

Deterrence is simply the consequentialist argument that punishment will discourage people from committing crimes—in theory, both deterring that specific criminal from recidivism (specific deterrence) and deterring others by making an example of her (general deterrence).131 Deterrence has always loomed large in international criminal law: “[F]or many, deterrence is the most important justification, and the most important goal.”132

As distinct from deterrence, retribution serves multiple purposes. Retribution underlies the classic lex talionis, eye-for-an-eye rationale for punishment that permeated ancient legal codes.133 Alternatively, retribution may relieve the international community of what Kant calls “blood guilt” (Blutschuld)134—that is, the complicity that would come of ignoring crimes. Under this theory, society simply has a moral obligation to punish bad acts. Retributivism motivates oft-heard demands to “bring criminals to justice,” and policies like amnesty for warlords are controversial because they feel like a subversion of that justice.135

This approach to retribution relates to the expressive function of international criminal law. The idea of condemnation has long played an important rhetorical role, even as early as the Nuremberg Tribunals.136 More recently, the ICTY has stated that retribution “is not to be understood as fulfilling a desire for revenge but as duly expressing the outrage of the international community.”137 Condemnation also gives voice to the victims of serious crimes by publicly recognizing their suffering. This was a theme reiterated in Security Council meetings leading up to the establishment of the ICTY.138 Many commentators now regard expression as the primary role of international criminal justice.139

Finally, criminal law can reconcile former enemies by isolating the parties responsible for conflicts. This prevents vengeful publics from attributing guilt to entire populations and provides an outlet for wartime frustrations. Historically speaking, one of the major benefits of the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials may have been the speed with which the Allies, West Germany, and Japan were subsequently able to reconcile their differences and align against the Soviet Bloc.140

On the other hand, there are some generally accepted goals of domestic law that international tribunals do not pursue. The most important of these are crime prevention and cost cutting. Domestic prisons prevent crime by incapacitating criminals and, in theory at least, by rehabilitating them. This matters because recidivism rates can be very high in domestic criminal law: one study across fifteen U.S. states reported that 46.9% of the prisoners in its sample were reconvicted within three years of their release.141 Incarceration therefore serves the important interest of promoting public safety.

In contrast, international convicts typically have neither the motive nor the means to reoffend. The prototypical international defendant is a former high-ranking political leader, often very old, who has been removed from power and stands virtually no chance of regaining it.142 Even with regard to rank-and-file international criminals, the conditions that initially motivated and permitted their crimes have almost always disappeared by the time of their trial, whether those conditions were concentration camps or oppressive military regimes. The rehabilitation of international convicts therefore does not affect public safety. Between their inability to regain their former power, increased international scrutiny that accompanies criminal conviction, and changed political circumstances, it is difficult to imagine recidivism in international criminal law.

This is not to say that courts should not attempt to prevent international crimes before they occur—indeed, the ICTY and ICC have made inroads in the prosecution of war criminals in ongoing conflicts. But when tribunals have managed to change the course of a conflict, they have done so almost exclusively through the initial indictment. For example, the ICTY’s indictment against Radovan Karadžić prevented him from attending the Dayton Peace Talks,143 and its indictment against Slobodan Milošević arguably facilitated Serbia’s transition to democracy by removing him from his Yugoslavian sphere of influence.144

Even this much interference with criminals still in power has been controversial. Indictment may inadvertently give the indictee some sort of notoriety-driven cachet;145 it threatens politically motivated abuse;146 it can discourage leaders from agreeing to peace deals that would expose them to criminal prosecution;147 and it may raise additional concerns of national sovereignty compared to the indictment of unseated leaders. So crime prevention is an uncertain goal of international law in the context of ongoing conflicts. It is even more tenuous in the context of early release: by the time that a court considers whether to set a prisoner free, the only factor with any implications for crime control is recidivism. Thus crime prevention should affect early release only if conditions amenable to further crimes still persist in the criminal’s home country, and if the court feels that she could relapse if set free—these conditions occur in an infinitesimal minority of cases.

Likewise, international tribunals may completely disregard the fiscal concerns that animate much of domestic parole policy. As discussed above, parole has sometimes been used as a means to cut costs, or at least to reduce the prisoner population to suit the penal system’s limited resources.148 International penology suffers from no such budgetary constraints. Modern international tribunals make agreements for the costs of detention to be borne by enforcing states rather than the tribunals themselves,149 and the enforcing states have strong reputational reasons to care for prisoners attentively. Even if the tribunals were to reimburse enforcing states for the costs of detention or to bear the costs themselves, the effect on their bottom lines would pale in comparison to the judicial salaries, administration fees, and facilities costs that make up the lion’s share of their budgets.150

As we will see, divergence between the goals of international law and domestic law has broad implications for early release policy: international law generally focuses on high-level issues like condemnation and reconciliation, rather than quotidian concerns like crime prevention and cost-cutting. The international emphasis on symbolism conflicts with the idea of presumptive early release. As Section III.A discusses, early release muffles the censure of the initial sentence, implying that the prisoner no longer deserves further punishment. The fact that this perceived reduction in deserts need not be tied to any actions on the part of the prisoner confuses the message of international criminal law; it also makes reconciliation more difficult by inflaming survivors and making the process of international justice seem arbitrary.

B. Relevant Factors

1. Cooperation After Sentencing

In a world of scarce resources, early release can ease the burden on Prosecutors by providing an ongoing incentive for convicts to cooperate with tribunals. This cooperation can take a number of forms. For example, a convict could testify against other criminals,151 or she could help the court to locate and confiscate assets that could then be used to compensate victims.152

The crucial point in either case is that a convict should only be rewarded for cooperation that she provides after trial. Any assistance provided to the Prosecutor before sentencing—guilty pleas, testimony against others, voluntary surrender, etc.—should have been taken into account in the initial sentence. As discussed above, the ICTY routinely double-counts guilty pleas both in sentencing and in early release deliberations; under the four factors, the guilty plea is treated both as evidence of remorse153 and as cooperation with the Prosecutor.154 This double-counting is unintuitive and therefore less transparent to lay observers than a one-time reduction in sentence. Although double-counting could theoretically result in equivalent sentences to single-counting by reducing the rewards of cooperation at sentencing (a move of questionable legality under the Nikolić rule155), the relative uncertainty of double-counting benefits no one. From the Prosecutor’s perspective, early release will only incentivize cooperation if defendants can rely on the general policy to grant early release to prisoners who have cooperated before sentencing. Such a system of incentives would take a considerable number of “free” initial releases to become credible, which would irk a Prosecutor who sought to maximize sentences. From the defendant’s perspective, early release based on pre-sentencing cooperation is uncertain and dependent upon the personal philosophy of the tribunal’s President. She would naturally prefer a guaranteed sentence reduction to a vague promise of early release. So trading pre-trial prosecutorial cooperation for early release is not only opaque and confusing, but a pretty bad deal for all parties to boot.

2. Humanitarian Concerns

Insofar as fairness demands humane conditions of imprisonment, another major motivation for early release will be inadequate prison facilities, particularly for old or sick prisoners. Humane treatment is an obvious ethical imperative; moreover, adequate care for defendants and convicts is important for the continuing political viability of international tribunals. Accusations of mistreatment following the death of former Yugoslavian President Slobodan Milošević (including claims that he had been poisoned156) underscored the need for international justice to be beyond reproach. The high profiles of international criminal defendants make tribunals particularly vulnerable to accusations of abuse.

This may explain the relative commonness of early release in international law relative to domestic practice. Three out of the seven criminals at the high-profile Nuremberg Trials were released early for old age or ill health;157 similarly, the ICTY often considers old age in its early release decisions.158

In contrast, few countries systematically release elderly or ill prisoners simply because of their age or health. In the United States, “[s]ince 1992, the annual average number of prisoners who received compassionate release has been less than two dozen.”159 The government of the United Kingdom has been similarly reluctant to release prisoners on compassionate grounds.160 Both countries grant compassionate release only at the discretion of the national government,161 which for political reasons may be skittish about showing sympathy for convicts.

An outlier is France’s 2002 rule that allowed for the release of prisoners whose “state of health is incompatible with long-term imprisonment,” regardless of time served or crime committed.162 But this move was notably controversial—for instance, the application of the policy to the case of ninety-two-year-old Vichy war criminal Maurice Papon drew criticism from within France and without.163 An international tribunal would probably draw similar flak for the humanitarian release of prisoners who had committed comparable crimes.

Where should such tribunals stand between these various policy options? Naturally, the need for compassionate release will depend on conditions of imprisonment and the capacity for the prison to provide treatment. Inadequate facilities pose a strong case for early release; on the other hand, it is difficult to argue that there is some sort of entitlement to early release based on old age alone. Even terminally ill prisoners (categorically eligible for release under the French system164) have no obvious right to die with their families rather than dying in prison. Depriving prisoners of contact with their families is a necessary and intentional part of incarceration.

Plainly, individual cases will vary, and the President will have to exercise a fair amount of discretion. Nonetheless, the economics of imprisonment suggest that international tribunals should on average be more conservative in granting early release than domestic ones. Elderly prisoners cost approximately three times more to incarcerate than average inmates165 and therefore strain the resources of domestic prisons.166 In contrast, as discussed in Section II.A, international tribunals may spend freely on medical care for their prisoners. Inmates at the famously luxurious United Nations Detention Unit (also known as the “Hague Hilton”) receive “top-notch medical care,”167 including extensive attention from local medical specialists and even transportation to foreign specialists as needed.168 It is difficult to conceive of circumstances in which prisoners would require treatment that could only be obtained through early release.

C. Irrelevant Factors

This Part has argued that early release should be motivated exclusively by changed circumstances. But that is not to say that any new information should qualify—there are several kinds of new information that tribunals still ought not to take into account, including various factors more commonly seen in domestic parole hearings. My analysis of these factors is underpinned by the contrast between the goals of domestic and international law.

1. Rehabilitation: Remorse, Recidivism, Good Behavior, and Reintegration

As Part I discusses, the ICTs and the ICC apply several factors in early release deliberations that might broadly be considered proxies for rehabilitation: remorse, risk of recidivism, good behavior, and potential for reintegration. Rehabilitation does not tell the whole story—for instance, expressions of remorse may hasten reconciliation, and good behavior may reduce costs—but it will be helpful in our analysis to understand why international tribunals have seen fit to encourage rehabilitation in early release policy, particularly since it was not one of the generally accepted principles of international law discussed in Section II.A.

Theorists generally see rehabilitation through either a consequentialist or a humanitarian lens. On the consequentialist view, rehabilitation is a purely instrumental means to the ends of crime prevention and economic prosperity: by “mak[ing] ‘honest citizens’ of former offenders, rehabilitative practices not only maximize the availability of useful, contributing members of society, but also protect society from future crime . . . .”169 But as Section II.A notes, neither crime prevention nor economics is an important consideration in international law. So consequentialist rehabilitation is a poor fit for international early release policy.

On the humanitarian view, prisoners have something like a right to rehabilitation. The theory is that criminal misconduct stems from moral underdevelopment, which is a failing of the state rather than a failing of the individual. Thus convicts have a right to rehabilitation in the same way that they have a right to basic education, as one of the privileges of citizenship. Put another way, criminals are not morally blameworthy so much as they are sick. They suffer from a kind of cognitive dysfunction that can and should be remedied by proper treatment.170

Humanitarian rehabilitation is controversial, in part because it seems to abrogate individual responsibility, and in part because rehabilitation is difficult to achieve in practice.171 For these reasons, the United States has in the past half century drifted away from the “rehabilitative ideal” and back toward retributivism.172 Nevertheless, humanitarian rehabilitation still retains some currency abroad. European countries in particular often recognize a right to rehabilitation as a subsidiary obligation of the welfare state173—for example, the German constitutional principle of the Sozialstaat174 demands that “the community must help prisoners with less-than-optimal social development to encourage their flourishing within society.”175

But there is no international Sozialstaat, nor any generally recognized right to rehabilitation in international law.176 Indeed, the influential 1955 United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners—passed when the rehabilitative ideal was at peak popularity—explicitly took the consequentialist view by declaring that “[t]he purpose and justification of a sentence of imprisonment or a similar measure deprivative of liberty is ultimately to protect society against crime.”177

Even assuming a right to rehabilitation, early release as actually practiced by international tribunals bears only an attenuated relationship to that right. Historically, unsupervised release has virtually never been used as a rehabilitative tool178: while it is conceivable that freeing those who express remorse might incentivize such remorse, it is much easier to imagine prisoners simply making disingenuous gestures of reform in order to win their freedom, as Plavšić did. Even a prisoner who maintained the façade up to the moment of her release would be free to retract past remorse under the usual unconditional terms of early release. An international tribunal would have no capacity to monitor such a prisoner or to impose the kind of conditions on parole that are meant to encourage rehabilitation. And even supervised parole has come under fire for its questionable ability to effect real rehabilitation.179

So it seems that neither the consequentialist nor the humanitarian approaches fully explain the centrality of rehabilitation in early release doctrine. But let us rephrase the question: why should international tribunals keep convicts locked up even after they have reformed? Doesn’t respect for the autonomy of the prisoner require us to give her a second chance if she has changed her ways?

The discussion above implies that rehabilitation makes no difference, insofar as rehabilitation did not motivate incarceration in the first place. If international tribunals only convicted criminals who posed an ongoing threat, the Hague Hilton would be practically empty. Similarly, if international tribunals took the resocialization of criminals seriously, they would centralize enforcement of sentences rather than farming them out across countries that differ significantly in their philosophies of rehabilitation,180 and they would encourage community reintegration through supervised parole rather than unconditional clemency. Thus the essential structure of incarceration and early release in international criminal law leaves little role for rehabilitation. We might think that this structure is misguided; yet if we limit ourselves to work within it, we must seriously doubt the role of remorse, recidivism risk, good behavior, and reintegration in early release deliberations.

Setting aside rehabilitation, can we explain these factors through other goals of international criminal law? Probably not. Probabilities of recidivism and reintegration are merely proxies for rehabilitative aims. Good behavior has an element of cost savings, insofar as including it as a factor encourages prisoners to behave themselves in prison; but as discussed above, tribunals need not generally be sensitive to the costs of imprisonment.

The only remaining factor is remorse. Arguably, apologies from war criminals can aid reconciliation and help victims obtain closure with respect to conflicts. Yet reconciliation is a largely empirical question, and as a matter of fact, remorse does not seem to achieve it. An unpleasant lesson of the ICTY so far has been that genuine remorse is difficult to determine, and that offering dramatic sentence reductions in exchange for shows of remorse is unlikely to inspire actual changes of heart.181 Moreover, victims often reject apologies even when they have been accepted by courts,182 and early release correspondingly damages reconciliation by sparking criticism from victims’ advocates.183 On the whole, undue emphasis on remorse seems to do more harm to reconciliation than good.

In sum, international tribunals err when they borrow rehabilitative factors from the law of parole. Rehabilitation is only a marginal concern of international criminal law; the damage to the expressive and reconciliatory content of sentences far outweighs any consequentialist or humanitarian benefits.

2. Social Instability

The ICC has proved somewhat more sensitive than the ICTs to the political effects of early release. Its Rules include another factor closely linked to reconciliation: “Whether the early release of the sentenced person would give rise to significant social instability.”184 This social instability could result from public outrage over early release, as in Plavšić’s case,185 or alternatively from the prisoner’s encouragement of bad acts by others after release.

The philosophy behind this rule strikes at the heart of fairness concerns in international criminal law. To punish a prisoner for the social instability that she causes is to punish her based on factors beyond her control—under the ICC’s approach, two convicts who committed crimes of equal gravity could receive unequal treatment solely because one of them received more press than the other.

Moreover, the expressive value of a theoretically objective judgment is somewhat diluted if its enforcement depends on public opinion. As some delegations to the Rome Statute conference pointed out, the proper role of an international judiciary is to administer agreed-upon penalties for agreed-upon crimes, not to make amorphous political determinations, even in the service of reconciliation.186

Naturally, each international tribunal must strike its own balance between political concerns and equity in sentencing. But the social instability factor at least raises serious questions about fairness and expressive law for the ICC to answer.

3. Gravity of Crimes

Finally, the gravity of crimes is another factor that pits the obligations of international law against the rights of defendants. The gravity of a prisoner’s crimes is already accounted for at sentencing—thus it does not constitute the sort of changed circumstance that merits early release. Just as a guilty plea should not be double-counted in favor of a criminal, the severity of her crimes should not be double-counted against her.

At the national level, judges sometimes solve this problem with sentences that preclude the possibility of parole.187 This allows them to designate crimes considered so heinous that even complete rehabilitation should not give rise to release.

No equivalent difficulty arises at the international level—under my theory, rehabilitation alone does not suffice, nor remorse, nor the inability to commit future crimes. The only way that a prisoner may be released before she serves her full sentence is by furnishing significant cooperation to the tribunal, or if the tribunal can no longer provide humane conditions of imprisonment.188 In the latter case, justice demands that she be released; in the former case, the tribunal need not seek her cooperation if it feels that she ought to stay in prison.

Moreover, the experiences of the ICTs suggest that tribunals cannot easily distinguish among applicants based on the gravity of their crimes anyway.189 By design, international justice only involves extraordinary crimes; the proposal in certain quarters “never [to] pardon certain crimes, like rape, murder and war crime”190 functionally recommends complete abolition of early release.

Consequently, the gravity of crimes is yet another factor better suited to domestic parole hearings than international criminal law.

|

D. Summary

The table above summarizes the analysis in Part II and compares the factors I have considered with the jurisprudence of the active international tribunals. As discussed, time served overshadows all other factors at the ICTs, and it remains to be seen exactly how the SCSL, STL, and ICC will implement the procedures in their Statutes and Rules. Nevertheless, this table proposes much stricter standards for early release than those presently applied by any of the major international tribunals.

III. objections

A. Expressive Law

One argument against my theory and for presumptive early release claims that international tribunals fulfill their function as soon as they deliver the initial sentence; that once the sentence stops ringing in the ears of the international community, to keep a criminal for much longer would simply be a waste of money and effort. Ostensibly, by widely publicizing the initial sentence and downplaying the subsequent early release, nations could express the same amount of indignation without the political inconvenience, harm to prisoners, or (admittedly small) monetary cost of keeping criminals behind bars.

Two major counterarguments suggest themselves. First, even assuming that the initial sentence were all that mattered in terms of expressive law—a substantial assumption—early release hobbles every other goal of international criminal law that jurists typically hold dear. Deterrence is impaired, because criminals will have committed crimes with relative impunity; retribution is obviously impaired; reconciliation is impaired insofar as victims’ groups are incensed at the generosity of early release.

Second, expressive law probably demands that the sentence given actually be served. The early release of convicted criminals after World War II clearly adulterated the international community’s condemnation of their crimes—the conventional view is that sentences followed by widespread clemencies in the late forties and fifties expressed nothing more than weak political willpower.191 As a factual matter, interested parties were fully aware of the extent of releases in the postwar period, and controversy continues to surround the generous early release policies of the ICTs today.192

On net, I suspect that the presumption of early release harms expressive law more than longer sentences help it. Commentators are struck by the apparent arbitrariness in releasing prisoners who neither show remorse nor help to prosecute other criminals. Victims see the presumption as reflecting a lack of seriousness on the part of the tribunals, rather than as an attempt to maximize expressive value. This system therefore hurts the credibility of international justice as a whole.

The symbolism of early release becomes particularly stark when we consider domestic analogues. Parole is not generally thought to impede the expressive value of criminal sentences, in part because parole still places burdensome restrictions on the freedoms of parolees. In contrast, domestic pardons and commutations usually mitigate the symbolism of the initial sentence, sometimes to controversial effect (consider, for example, President George W. Bush’s commutation of Lewis “Scooter” Libby’s prison sentence,193 or President Jimmy Carter’s commutation of the sentence of brainwashed heiress-cum-terrorist Patricia “Patty” Hearst194). As Part I discusses, early release in international criminal law is much closer to commutation than to parole; thus it implies a disclaimer of the initial sentence in much the same way as commutation would in domestic law.

Justice does not end with sentencing—enforcement is an equally important task in international criminal law. Inevitably, expressive law demands that criminals actually be punished.

B. Incomplete Information

A second objection to my theory asks the following questions: What if the ICTY wished to enforce its full sentences, but was simply unable to do so because of excessively poor conditions of imprisonment? It might have had a difficult time criticizing said conditions or moving the prisoner without insulting the enforcing state. Similarly, what if a defendant were to cooperate with the Prosecutor subsequent to trial in such a way that public acknowledgement would endanger her or her family? The President would be obliged to release the prisoner without explaining the rationale behind the release. If sufficiently common, such cases could even steer the course of early release jurisprudence outside of these exceptional cases—an uninformed successor President might analogize to a past case in which release was granted without realizing the hidden mitigating factors that drove that case.195

This story is problematic, but highly speculative. Although we necessarily cannot know what information Presidents of the Tribunals have chosen not to make public, it seems unlikely that they would exclude significant factors from their early release decisions—most importantly because of the predictable corrupting effect it would have on subsequent decisions. Presidents could simply include information in their early release decisions and redact them as necessary.

And, in fact, there are several decisions where redactions have partly obscured the underlying legal reasoning.196 But these cases are the exception rather than the norm, and it is possible to form a complete picture of policy without them. It is unlikely that redactions, or even more speculatively, judicial consideration of factors entirely excluded from the written decisions, have biased our conception of early release doctrine.

In sum, neither of the above-cataloged objections can scuttle the theory set out in Part II.

IV. implications

The most important payoff of Part II is that international courts should award early release far less often than they do in the status quo. Criminals are significantly more likely to satisfy the criteria used by the ad hoc Tribunals or ICC than the more restrictive ones that Part II lays out. Going forward, judges should therefore limit early release to exceptional cases involving changed circumstances.

However, courts like the ICTR, ICTY, and MICT may risk substantial inequality to prisoners who have not yet reached the two-thirds mark if they abruptly change their policies on early release. Although their Statutes merely require them to make decisions based on “the interests of justice and the general principles of law,”197 it is reasonable to think that those principles include equal treatment for similarly situated prisoners.

At this point, then, prospective policy-building should focus on changes at the ICC, the SCSL, and the STL, none of which have considered the release of any prisoners. Aside from the factors laid out in Part II and the concomitant tightening of clemency, this Part lays out two other suggestions for consistent and equitable early release policy.

First, tribunals should take care to grant only the kinds of release that they have been authorized to grant, and draw from domestic law only insofar as it relates to that variety of release. The domestic law of parole forms a poor basis for the international law of commutation. International tribunals have different aims and fewer enforcement-related resource constraints, and should act accordingly.

On this count, awareness is key. Judges should take some time before even hearing their first application for early release to agree on general principles by which to conduct the proceedings. I mean by this not only agreement on the criteria for early release, although of course these should be established as well. I also mean that judges should be able to explain, at least to themselves, why things such as the gravity of crimes or a guilty plea should be considered both at sentencing and at early release, or why a criminal should be freed in the absence of any changed circumstances.

Second, tribunals should establish stable advisory panels to advise them on early release. Much of the inconsistency in the ICTs’ early release practice occurred between succeeding Presidents. The tribunals do not formally subscribe to stare decisis in their judgments, although they are “reluctant to overturn prior doctrinal pronouncements due to concerns of stability in the law.”198 The Presidents have been even less stringent in keeping consistent standards of early release. Some draw on the criteria of domestic parole more than others;199 some separately address each of the four factors, while others address only the most relevant;200 one has even used his authority to grant conditional, rather than unconditional, release.201

Moreover, because each President handles enforcement issues like early release as only one of her many duties—she sits as a judge, makes administrative rulings, and serves as the public face of the Tribunal—she has less time to devote to the construction of standard, robust procedures. As a result, each application has a sui generis feel that sacrifices judicial experience and consistency for a slight gain in flexibility.

Just as bad, the lack of a dedicated decisionmaker may necessitate excessively simplistic criteria for early release. It is possible that the two-thirds presumption favored by the ICTs arose out of a desire for simple bright-line rules to compensate for variance between judges. The revolving door of Presidents thus not only hurts consistency, but also allows the crudest factors to dominate early release considerations.

The ICC Rules ameliorate this problem by having a panel of three judges sit on each sentence reduction hearing.202 By requiring discussion and consensus before each release, the ICC forces panels to reflect on the purposes of early release before making a decision. Moreover, regularly rotating hearings between judges may encourage the ICC to create objective, standard sentence reduction procedures as a matter of convenience.

On the other hand, spreading authority from a single judge to all of the judges further reduces the incentive and opportunity for any particular judge to develop expertise in early release. The ultimate solution would be a permanent advisory board, consisting of specialists from a number of different countries. The board could complement the judicial expertise of the panel of judges, smooth out differences between successive panels, and keep the proceedings focused squarely on international law instead of wandering into domestic practice.

The above are just two of many possible structural suggestions for future courts to consider. The most obvious substantive reform would simply be to restrict criteria to those suggested in Part II and to eliminate any presumption of early release. These changes alone would go a long way toward solving current policy problems.

Conclusion

In this Note, I have attempted to explain the historical roots of the modern two-thirds standard, to offer an alternative theory, and to suggest some basic improvements. Early release poses difficult questions—theorists differ on the goals of international criminal law, and no set of policy recommendations can address every concern. Nonetheless, present doctrine is both theoretically shaky and politically unpopular. Courts like the ICC would do well to confront its shortcomings.

See Ian Traynor, Leading Bosnian Serb War Criminal Released from Swedish Prison, Guardian, Oct. 27, 2009, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/oct/27/bosnian-serb -war-criminal-freed.

See Bosnian Serb Ex-Leader Plavsic [sic]Returns to Belgrade After Release, Xinhua, Oct. 28, 2009, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90001/90777/90853/6796482.html; Milos Jelesijevic, BiljanaPlavsic [sic] Arrived in Belgrade, Serbia, Demotix, Oct. 27, 2009, http://www.demotix.com/news/biljana-plavisic-arrived-belgrade-serbia; Traynor, supra note 1.

See Prosecutor v. Plavšić, Case No. IT-00-39 & 40/l-ES, Decision of the President on the Application for Pardon or Commutation of Sentence of Mrs. Biljana Plavšić, ¶¶ 1, 6 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for the Former Yugoslavia Sept. 14, 2009) [hereinafter Plavšić’s Early Release], http://www.icty.org/x/cases/plavsic/presdec/en/090914.pdf (public redacted version); Traynor, supra note 1.

Prosecutor v. Plavšić, Case No. IT-00-40-I, Indictment (Int’l Crim. Trib. for the Former Yugoslavia Apr. 3, 2000), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/plavsic/ind/en/pla-ii000407e.pdf.

Biljana Plavsic [sic]: Serbian Iron Lady, BBC, Feb. 27, 2003, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi /europe/1108604.stm.

Statements of Guilt—Biljana Plavšić, Int’l Crim. Trib. for Former Yugoslavia, http:// http://www.icty.org/sid/221 (last visited Jan. 17, 2013).

Prosecutor v. Plavšić, Case No. IT-00-39 & 40-PT, Plea Agreement, ¶ 3 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for the Former Yugoslavia Sept. 30, 2002), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/plavsic/custom4 /en/020930plea_en.pdf.

Prosecutor v. Plavšić, Case No. IT-00-39 & 40/1-S, Sentencing Judgement, ¶ 134 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for the Former Yugoslavia Feb. 27, 2003), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/plavsic /tjug/en/pla-tj030227e.pdf.

Daniel Uggelberg Goldberg, Bosnian War Criminal: ‘I Did Nothing Wrong,’ Local, Jan. 26, 2009, http://www.thelocal.se/17162/20090126/#.UPhieiefuSo; Simon Jennings, Plavsic [sic]Reportedly Withdraws Guilty Plea, Inst. for War & Peace Reporting, Jan. 31, 2009, http://iwpr.net/report-news/plavsic-reportedly-withdraws-guilty-plea.

ICTY: Sweden Releases Biljana Plavsic [sic], Int’l Just. Trib. 2 (Oct. 28, 2009), http://sites.rnw.nl/pdf/ijt/IJT-No92.Finale.pdf.

Bojana Barlovac, BiljanaPlavsic [sic] Arrives in Belgrade, Balkan Insight, Oct. 27, 2009, http://old.balkaninsight.com/en/main/news/23201.

See, e.g., Mark B. Harmon & Fergal Gaynor, Ordinary Sentences for Extraordinary Crimes, 5 J. Int’l Crim. Just. 683 (2007) (arguing that sentences are too short); Damien Scalia, Long-Term Sentences in International Criminal Law, 9 J. Int’l Crim. Just. 669 (2011) (arguing that long-term sentences violate human rights standards).

Prosecutor v. Bagaragaza, Case No. ICTR-05-86-S, Decision on the Early Release of Michel Bagaragaza (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Rwanda Oct. 24, 2011) [hereinafter Bagaragaza’s Early Release], http://www.unictr.org/Portals/0/Case/English/Bagaragaza/decisions/111024.pdf.

James Karuhanga, ICTR Early Releases Raise Eyebrows, New Times, Mar. 10, 2012, http://www.newtimes.co.rw/news/index.php?i=14927&a=51185.

See Rwanda Leader Accuses West of Leniency for Genocide Suspects, Agence Fr.-Presse, Apr. 7, 2012, http://www.rawstory.com/rs/2012/04/07/rwanda-leader-accuses-west-of-leniency-for -genocide-suspects.

Boris Pavelić, Josipovic[sic] CriticisesEarly Release of War Criminals, Balkan Insight, Mar. 14, 2012, http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/josipovic-criticises-earlier-release -of-war-criminals.

Prosecutor v. Dyilo (Lubanga), Case No. ICC-01/04-01/06, Decision on Sentence Pursuant to Article 76 of the Statute (July 10, 2012), http://www.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/doc /doc1438370.pdf.

See Valerie Hébert, From Clean Hands to Vernichtungskrieg, in Reassessing the Nuremberg Military Tribunals: Transitional Justice, Trial Narratives, and Historiography 194, 202-05 (Kim C. Priemel & Alexa Stiller eds., 2012) (addressing Germany); Henry L. Shattuck, The Interim Mixed Parole and Clemency Board, 76 Proc. Mass. Hist. Soc’y 3d 68, 69-70 (1964) (addressing Germany); Sandra Wilson, After the Trials: Class B and C Japanese War Criminals and the Post-War World, 31 Japanese Stud. 141, 143 (2011) (addressing Japan).

Compare Judges, United Nations Mechanism for Int’l Crim. Tribs., http:// unmict.org/judges.html (last visited Dec. 4, 2013), with The Chambers, Int’l Crim. Trib. for Rwanda, http://www.unictr.org/tabid/103/Default.aspx (last visited Dec. 4, 2013), and The Judges, Int’l Crim. Trib. for Former Yugoslavia, http://www.icty.org /sid/151 (last visited Dec. 4, 2013). In particular, the Appeals Chambers of the ICTR and ICTY are identical. Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda art. 13(4) (amended Jan. 31, 2010) [hereinafter ICTR Statute], http://www.unictr.org/Portals /0/English/Legal/Statute/2010.pdf.