Leviathan and Interpretive Revolution: The Administrative State, the Judiciary, and the Rise of Legislative History, 1890-1950

abstract. A generation ago, it was common and uncontroversial for federal judges to rely upon legislative history when interpreting a statute. But since the 1980s, the textualist movement, led by Justice Scalia, has urged the banishment of legislative history from the judicial system. The resulting debate between textualists and their opponents—a debate that has dominated statutory interpretation for a generation—cannot be truly understood unless we know how legislative history came to be such a common tool of interpretation to begin with. This question is not answered by the scholarly literature, which focuses on how reliance on legislative history became permissible as a matter of doctrine (in the Holy Trinity Church case in 1892), not on how it became normal, routine, and expected as a matter of judicial and lawyerly practice. The question of normalization is key, for legislative history has long been considered more difficult and costly to research than other interpretive sources. What kind of judge or lawyer would routinize the use of a source often considered intractable?

Drawing upon new citation data and archival research, this Article reveals that judicial use of legislative history became routine quite suddenly, in about 1940. The key player in pushing legislative history on the judiciary was the newly expanded New Deal administrative state. By reason of its unprecedented manpower and its intimacy with Congress (which often meant congressmen depended on agency personnel to help draft bills and write legislative history), the administrative state was the first institution in American history capable of systematically researching and briefing legislative discourse and rendering it tractable and legible to judges on a wholesale basis. By embracing legislative history circa 1940, judges were taking up a source of which the bureaucracy was a privileged producer and user—a development integral to judges’ larger acceptance of agency-centered governance. Legislative history was, at least in its origin, a statist tool of interpretation.

author. Associate Professor of Law, Yale Law School. For valuable conversations about the project, I thank Bruce Ackerman, Ian Ayres, James Q. Barrett, Joseph Blocher, James Brudney, Aaron-Andrew Bruhl, Josh Chafetz, Robert Ellickson, Daniel Ernst, William Eskridge, Heather Gerken, Abbe Gluck, Bob Gordon, Oona Hathaway, Daniel Ho, Christine Jolls, Dan Kahan, John Langbein, Robert Lieberman, Yair Listokin, John Manning, David Marcus, Jerry Mashaw, Tracey Meares, Thomas Merrill, Robert Post, Edward Purcell, Cristina Rodríguez, Susan Rose-Ackerman, Ted Ruger, Reuel Schiller, Alan Schwartz, Peter Strauss, Adrian Vermeule, Jim Whitman, and John Witt; and audiences for talks at Duke, Stanford, Yale, and the annual meeting of the American Society for Legal History. The quantitative aspect of the project was made possible by the work of several excellent and dedicated research assistants: Allyson Bennett, Glenn Bridgman, Halley Epstein, Miles Farmer, Andrew Hammond, Tian Huang, Steven Kochevar, Stephen Petrany, Emily Rock, Clare Ryan, and Karun Tilak. For aid in obtaining sources, I thank the staffs of the Yale Law Library (particularly Sarah Kraus), the Harvard Law Library, the Columbia University Center for Oral History, the Library of Congress, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library, the Margaret I. King Library at the University of Kentucky, the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan, and the National Archives; and Kim Dixon, Karen Needles, Doug Norwood, and Susan Strange. Glenn Bridgman generously shared data with me from his own research project. Alex Hemmer and his fellow members of the Yale Law Journal performed valuable work in editing and publishing the piece. I am grateful to Yale Law School for financial support. All errors are my own.

Introduction

When a legislature enacts a statute, it leaves behind a history: the revisions that lawmakers made to the bill, the things they said about it during committee deliberations and floor debates, and the public input they officially received on it from experts and other witnesses. Should a court, when interpreting the act, consider that history?

For a generation, the field of American statutory interpretation has burned with controversy over this question. The controversy is a novelty of the last twenty-five years. In the 1980s, legislative history was uncontroversial and very common. It appeared in more than half the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinions on federal statutes.1 In the high courts of leading states like New York, it likewise appeared frequently.2 Using this material meant that judges were accustomed to engaging actively and openly with legislators’ discourse and policy reasoning. Beginning in the late 1980s, however, a movement of judges and lawyers—led by Antonin Scalia—began to argue that this familiar interpretive resource was pernicious and should be banished from the judicial system. They urged a textualist method of statutory interpretation that would ignore an act’s legislative history and focus more narrowly on its words. The legislative history of an act, warned Scalia and his allies, was a devil’s playground: it contained such a huge number of assertions about the act’s meaning, and those assertions were so contradictory and so easily inserted by manipulative politicians or lobbyists, that willful judges could always find support for whatever personal preferences they wished to impose. Adherence to the ordinary meaning of the text—the words on which lawmakers formally voted according to constitutional procedures—would do better at keeping judges accountable to the democratic will. Critics responded that Scalia was a false prophet. His method, they said, would not deliver the determinacy he promised, for text was often ambiguous (or became ambiguous when overtaken by events unforeseen by lawmakers), so textualist judges could just as easily impose their preferences, and all the more insidiously, since they would do so under the apolitical cloak of “ordinary meaning.” Besides, added the critics, legislation was meaningless without reference to policy, and what better source for understanding a statute’s policy than legislative history?3

Whichever side is right, there is no doubt that judicial practice has moved dramatically in Scalia’s direction (even if his colleagues have not formally converted to his principle of complete exclusion). The proportion of U.S. Supreme Court opinions citing legislative history in statutory cases has fallen by more than half since the 1980s.4 The number of citations per statutory case has fallen even more steeply.5 At the state level—where legislatures have recently begun publishing legislative history far more extensively than in the past—courts have drawn upon textualist ideas to limit the new material’s use.6 Even leading defenders of legislative history concede parts of the textualist critique and look back with some embarrassment on how freely and easily the federal courts used such material twenty-five years ago.7 “[M]any contemporary courts,” when they do cite legislative history, seem to “apologize” for doing so.8

We are living through what appears to be an interpretive revolution. But we do not fully understand what (for better or worse) we are losing by it. That is because we do not have an adequate account of how and why judicial reliance upon legislative history—the once-dominant method that is now under attack—came to dominance in the first place. Further, an account of legislative history’s rise would provide us with a better understanding of how interpretive revolutions happen, which may be useful knowledge for those who want to consummate the present revolution and for those who want to prevent its consummation. The task of this Article is to provide that account.

To be sure, we do have a partial sense of the story, in some of its general outlines. Originally, English and American judges cited no legislative history, for none was available. In the early modern era, the English Houses of Parliament not only refrained from recording or publishing their debates but actually prohibited their publication, for the members feared the scrutiny of the crown and viewed themselves as an elite body that should be insulated from immediate popular pressure.9 With no tradition of legislative openness in the mother country, the American colonial assemblies also did not publish their deliberations.10

Eventually, however, English and American judges did have to confront the question of whether to use legislative history, for as both societies became more democratic, such material came to be published copiously. In 1771, Parliament began permitting publication of its debates, and by the mid-1800s, the famous Hansard company received public subsidies to publish them in great detail.11In the United States, Congress published its journal (a skeletal procedural record)12 from 1789 onward and soon began allowing private printers to publish its floor debates. These early reports were sometimes incomplete, irregular, and even biased, but this changed in 1850 when the Congressional Globe became semi-official, publishing a complete and timely verbatim transcript, supported by a congressional subsidy.13Eventually Congress started doing the same thing itself, establishing the in-house Congressional Record in 1873.14 The Record of the 46th Congress (1879-81) ran to 10,000 pages; of the 56th (1899-1901), to 10,000 again; of the 66th (1919-21), to 22,000; and of the 76th (1939-41), to 38,000. Meanwhile, Congress’s committees began publishing reports on all the public bills they sent to the floor. The House made such reports mandatory in 1880, and Senate committees were issuing them on the majority of bills by about 1900.15 These committee reports, combined with informative documents that committees ordered printed, made up a “Serial Set” that totaled 2,000 volumes by 1880, added another 2,000 by 1900, another 4,000 by 1920, and another 2,500 by 1940. And shortly after 1900, the committees began frequently publishing their hearings: the annual number stood at about 100 in 1900 and jumped into the range of 500-650 per year for 1910, 1920, 1930, and 1940.16 (The penchant for publishing did not extend to the state legislatures: even in the 1940s, almost none of them had ever recorded their floor debates or committee hearings, or issued substantive reports of standing committees.17)

Thus, English courts and U.S. federal courts had to decide whether to use the legislative history that was proliferating. The English judges shut their eyes to it. They had imposed an exclusionary rule in the era before 1771, when publication of parliamentary deliberations had been illegal, and they maintained that rule even as reports of the debates became lawful and available.18 American judges and treatise-writers followed the English rule from the late 1700s through the mid-1800s.19 Then, in the 1870s and 1880s, U.S. federal judges in a handful of cases made small, incremental departures from the rule. Next, in 1892, the U.S. Supreme Court in Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States20 relied upon committee reports (among other interpretive tools) to override what it admitted to be the literal meaning of an act of Congress.21 Holy Trinity would become the leading case for a new American rule that legislative history was permissible in statutory interpretation.22 Meanwhile, English judges—plus those of Commonwealth countries like Canada and Australia—held fast to the exclusionary rule. They relaxed it only in the 1980s or later, and even now, they do not use legislative history as much as American courts.23

So much we know. What we lack is an account of how legislative history went from being a permissible tool of American statutory interpretation to being the normal, routine, and expected tool that it had become by the time of Scalia’s attack. One might assume that, in an adversary system, permissibility automatically leads to normalization. That is, once the judiciary says it will consider a certain kind of source, lawyers will instantly compete with each other to cite ever more of that source. But nobody has proven that assumption with respect to legislative history. And it may well be wrong. The opinion in Holy Trinity itself did not consciously reject the English rule; it simply ignored it without comment. And, as some leading present-day scholars point out, legislative history is more (perhaps far more) difficult and costly for lawyers to research than other legal sources, such as case law and statutory text.24 Given the offhand quality of Holy Trinity and the headaches of using the source it made permissible, we must ask: why did this case become a landmark—a license for a method that has cost millions of billable hours—instead of being forgotten as an obscurity?

What we need is an account of legislative history’s rise as a matter of practical, workaday lawyering and opinion-writing. Or, to speak in more academic terms, we need an institutional account. Who were the lawyers and judges who started the pattern of routinely using a source often considered intractable? How did they manage to do it? What drove them?

The existing literature does not answer this question, though it does provide some valuable background and a few pieces of the puzzle. There has been major work on the intellectual history (as distinct from the institutional history) of judicial use of legislative materials. This work focuses on leading cases, treatises, and law review articles from the first half of the 1900s. It shows how the federal judiciary widened the scope of permissibility on an incremental basis, to include more categories of legislative documents, and it traces changes in high theory about the value of legislative history in interpretive thinking.25 These intellectual developments play a role in the institutional story that I tell below.

In addition, there have been several quantitative studies of legislative history usage, though mostly confined to the period from the 1950s to the present.26 One of the most careful of these studies finds that the percentage of Supreme Court statutory opinions using legislative history rose between the 1950s and 1980s and plummeted thereafter. Crucially, the level in the 1950s was substantially higher than it is today.27 Thus, our threshold question is how the Court even got to the level of the 1950s. By then, legislative history had already become normal. (Indeed, the first edition of a standard manual on appellate advocacy in 1950 said that “an advocate in the federal courts . . . cannot afford to ignore legislative history” and “should routinely check” it.28) There have been four quantitative studies of U.S. Supreme Court citations that reach back into the pre-1950 era and include legislative history.29 Taken together, these studies suggest a surge—perhaps a radical one—in the Court’s usage sometime in the 1930s or 1940s. But they do not allow us to state the point with confidence or precision. All four have major limitations in method or scope: two fail to control for the number of statutory cases,30 a third draws cases from only four years within the whole period 1925-50,31 and the fourth focuses exclusively on tax law.32 Also, only one of the four studies focuses mainly on legislative history, and only one (not the same one) focuses mainly on the pre-1950 period, so none of the four pay much attention to the pre-1950 shift toward legislative history that seems to appear in their datasets.33 Further, all four studies focus mainly on the Court’s opinions, saying little to nothing about the role of lawyers in bringing this hard-to-use source to the fore.34 A satisfying institutional account demands more work.

I begin that work in Part I, setting forth quantitative data on Supreme Court use of legislative history in every fifth year from 1900 to 1950, including (1) the number of cites per statutory case and (2) the proportion of statutory cases with any cites. The first metric is low through 1935, then suddenly increases four-fold in 1940, entering a range that becomes the “new normal” through 1950. Similarly, the second metric creeps up to 20% by 1935 but then more than doubles (to 44%) in 1940, again entering a range that becomes the “new normal” (and is comparable to the data from prior studies on the 1950s). In other words, the use of legislative history became normalized very suddenly, sometime in 1935-40. I then present comparable data on every single year from 1930 through 1945, finding that the radical break can be pinpointed to the year 1940 almost exactly. I then assemble qualitative evidence confirming a transformative shift toward legislative history as a matter of everyday practice just around 1940.

This finding has three implications. First, it shows that legislative history remained rare for decades after Holy Trinity. Permissibility did not automatically lead to normalization. Second, it establishes that the American turn to legislative history as a routine interpretive source originated at the federal level, not the state level, for scholars in the 1940s universally found that state courts’ use of legislative history was minimal, largely because the state legislatures at the time published so little of it.35 Third, identification of the years 1940-45 as the opening years of the “new normal” points us to the next step in our inquiry: we must analyze those years intensively to see which judges and lawyers were most responsible for the advent of the new regime.

In the remainder of the Article, I argue that normalization was caused simultaneously by two interrelated factors. First was the appointment of new Justices with a new openness to legislative history. Second was the rapid growth of a federal administrative state with unprecedented institutional capacity to use legislative history to its advantage.

Part II discusses the appointment of new Justices with new intellectual attitudes. The surge of legislative history in 1940 coincided fairly closely with the appointment of several new progressive Justices by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Progressive Justices generally cited legislative history at a much higher rate than Justices with more classical views. This makes sense: as the literature on the intellectual history of statutory interpretation indicates, progressive legal ideology counseled that judges should recognize the inevitable indeterminacy of traditional legal sources—whether common-law doctrinal formulas or statutory texts—and engage consciously and transparently in the policy choices that were inevitable in legal decision-making. As progressive academics began arguing around 1940, legislative history could be of great value in guiding and deepening a judge’s policy reasoning, particularly if the judge used the history to reason at a high level of generality—discerning the legislature’s overall objective and then reasoning “downward” to find a disposition of the specific case that best implemented that objective. Based on my reading of numerous cases from the period, I do think these progressive academic views informed the Justices’ increasingly copious use of legislative history during the early 1940s.

Still, the period’s theoretical innovations are not a complete explanation for the change in workaday judicial practice. While there were many opinions that conformed to the academic focus on general intent, there were many others that went in a different direction, reflecting a more old-fashioned tendency to consult the history in search of lawmakers’ specific preference for how to dispose of the fact situation at issue, without much policy reasoning. Another difficulty with attributing the change entirely to the fresh ideas of new Justices is that even the old Justices greatly increased their citations to legislative history between the pre-1940 and post-1940 stages of their careers.

For a true understanding of normalization, we must appreciate the crucial role of the newly expanded federal administrative state—the leviathan—in providing legislative history to the Court. Congress was such a complex body that neither the Justices nor ordinary lawyers were capable of analyzing its discourse routinely and systematically, no matter how intellectually committed they might have been to doing so. Only the federal bureaucracy had the intimacy with Congress and the institutional capacity to drive the interpretive revolution. Certain present-day scholars posit that the federal bureaucracy, when it litigates, uses legislative history more, and better, than does any other litigant,36 but this Article is the first to confirm that idea empirically.

Part III traces the administrative state’s leading role in normalization. I begin by setting forth data, for a large sample of Supreme Court statutory opinions in the transformative years 1940-45, on “matches” between the legislative history citations appearing in the Court’s opinions and those appearing in the corresponding briefs.37 Of the Supreme Court’s statutory cases in 1940-45, 78% were briefed by the federal government, and these accounted for 86% of the legislative history citations. In the federally briefed statutory cases, the “matches” indicate that 33% of the legislative history citations came only from the federal brief, 22% from the federal brief and at least one non-federal brief, 10% from at least one non-federal brief and not from a federal brief, and 34% from no brief. In other words, it was 50% more common for the Justices to take a citation exclusively from the federal lawyers than to take one jointly from federal lawyers and non-federal lawyers. And it was more than three times more common for the Justices to take a citation exclusively from federal lawyers than to take one exclusively from non-federal lawyers. (Consistent with this, the data from the cases without federal briefs indicate that the Court had to do more work by itself in those cases. Only 45% of the citations matched any brief at all; the remaining 55% matched no brief.)

The dominance of the federal government in providing legislative history to the Justices makes sense when we consider some background. First, researching legislative history was indeed more difficult, by a wide margin, than researching case law or statutory text. Telling which documents were relevant required sophisticated knowledge of the legislative process; the documents were often hard to obtain; and once obtained, they were voluminous, internally disorganized, and indexed poorly, if at all. In finding this material and translating it into legal argument, federal agencies and the Department of Justice—whose research underlay the briefs submitted by the Solicitor General to the Supreme Court—had major advantages. Their manpower (both in lawyers and law librarians) dwarfed all other organizations in the country. They each devoted themselves full-time to implementing one or a few statutes, so they could amortize the cost of researching the history of those statutes over many cases. Further, they had uses for legislative history beyond litigation (e.g., to guide program implementation). Most important, they were constantly communicating and negotiating with Congress over how to administer (and whether to amend) the statutes in their charge, which meant they were intimately engaged with the congressional process. Indeed, agency officials and Justice Department lawyers actually authored a large amount of legislative history—either in their own name (such as testimony at hearings) or as ghostwriters (of congressmen’s committee reports and floor speeches). Executive branch ghostwriting of congressional discourse has always been a feature of American government, but it appears that the 1930s and 1940s were the high point of this phenomenon: the volume of legislative activity was unprecedented, but Congress did not seriously begin building up its own internal staff until the late 1940s. Until then, congressmen were remarkably dependent on agency personnel for their words. Thus, the judiciary took up legislative discourse as a normal tool of interpretation at the very moment when the executive branch’s dominance of the legislature was at its height.

Part III also provides data on changes in the federal government’s briefing practices across the period 1930-45. The government briefed little legislative history up to the mid-1930s but then suddenly leaped into using such material. This timing is consistent with the idea that the government’s routine use of legislative history was a precondition for the Court’s routine use of it. Because the roots of the interpretive revolution seem to be found in the government’s dramatic increase in use, I consider how that increase happened. There were two stages. The first came in about 1936, when federal lawyers adopted legislative history as a weapon to defend New Deal statutes against constitutional challenges, citing congressional documents to show that Congress had made the factual findings requisite to the exercise of its enumerated powers (e.g., that the problem targeted by the statute truly affected interstate commerce). Interestingly, the Court picked up very few of these citations: conservative Justices eschewed legislative history because they clung to abstract, formalistic tests of constitutionality, while liberal Justices eschewed it because they considered judicial scrutiny of legislative findings to be improper judicial activism. Then came the second stage of the federal government’s leap into legislative history: in about 1939-40, federal lawyers began copiously using such material to argue “pure” questions of statutory interpretation, unconnected to constitutional issues. It seems that this second and more lasting shift in briefing practice arose from (1) the accumulation of a critical mass of institutional capacity by the agencies and DOJ and the consequent peak in Congress’s dependence on those organizations; (2) the great familiarity that agencies and DOJ had with legislative history, arising from their engagement with Congress; and (3) the incentive created by the adversary system to wield a weapon that is less available to one’s opponent.

In addition, Part III considers the capacity (such as it was) of non-federal lawyers to brief legislative history. Non-federal lawyers generally briefed legislative material less than did the federal government, but a few of them used such material heavily. Who were these lawyers? For the most part, they were congressional lobbyists, and often they had lobbied Congress on the very bill that had become the statute at issue in the case. This makes sense: on any given statute, the relevant private lobbyists were the only people outside the federal bureaucracy who had knowledge of congressional activity rivaling that of the bureaucracy.

Further, Part III examines the Court’s own internal capacity to research legislative history. As noted above, my sample indicates that 34% of the citations in federally briefed cases (plus 55% of the citations in other cases) matched no brief, suggesting the Court did the research itself. Consistent with this, the Court, in the years leading up to 1940, had rapidly acquired institutional capacity far exceeding that of any judicial tribunal in American history. Though the Justices had long employed one clerk each, it was only in the 1930s that all of them began filling those positions with elite recent graduates capable of advanced research. Another reason for the Court’s high capacity was the paucity of its cases: the Judiciary Act of 1925 had empowered the Justices to decide what cases they would hear, and they immediately began hearing a lot fewer. This was a precondition for the 1940 surge in legislative history, though not the immediate trigger. That said, it should be noted that some part of the 34% figure represents not the Court’s internal capacity but the hidden influence of the federal leviathan: citations that matched no brief sometimes came from the administrative state through back channels (e.g., ex parte judicial requests for agency research, or agency donations of legislative history scrapbooks to the Court’s library).

Altogether, the litigation process that normalized legislative history was radically modern. Whereas the Anglo-American judge was traditionally conceived as a passive referee choosing which of two formally equal parties had the better argument, the Supreme Court’s normalization of legislative history depended significantly on the Court’s independent research capacity. And when the Court did rely on the lawyers, it did not draw equally from “Doe” and “Roe” but instead depended heavily on an extraordinary kind of party: the now-fully-grown federal leviathan, which in 1940 had far more lawyers and legal researchers than any organization America had ever seen—plus an intense, ongoing relationship with Congress that gave it a uniquely systematic knowledge of legislative history. The extraordinary nature of the process helps explain why legislative history was never a major part of American statutory interpretation until far into the twentieth century. This is consistent with my finding, noted at the end of Part III, that the lower courts did not play a significant role in providing legislative history to the Supreme Court. Judicial use of legislative history did not “bubble up” from below. It was invented at the high court and then trickled down.

In Part IV, I argue that legislative history was—at least in its origin—a statist tool of statutory interpretation. This was true not only because the bureaucracy was a privileged provider of such material to the judiciary, but also because the bureaucracy was a privileged participant in congressional discourse—a status that it could leverage in its briefs. Indeed, many of the government’s invocations of legislative history before the Court aimed to show that (1) congressmen intended for a bill to mean what the agency had told them it meant, or (2) congressmen, having been apprised of how an agency was interpreting a particular statute, acquiesced in the agency’s view. And these were only the explicit briefs; many other governmental invocations of legislative history rested on congressional utterances that had been ghost-written (or at least influenced) by agencies and thus reflected the bureaucratic agenda. Thus, legislative history frequently served to deliver the bureaucracy’s views to the judiciary clothed in the mantle of congressional authority, right at the moment when the Court had recognized such authority as virtually unlimited in the economic sphere. The Court’s acceptance of legislative history as a normal interpretive source was a key element of its larger acceptance of an agency-centered vision of governance.

Though fitting, the “statist” label requires two qualifications. First, the Supreme Court did acquire some capacity to research and evaluate legislative history unilaterally, even though such material was outside the traditional judicial “comfort zone.” By acquiring this capacity, the Roosevelt Justices—even as they acquiesced in an agency-centered regime—preserved a measure of the independence that has characterized the attitude of the federal judiciary toward the federal bureaucracy over the long run of U.S. history. Second, a small, emergent group of lawyer-lobbyists became highly proficient at influencing legislative history in the Capitol and briefing it at the Court. Through these lawyer-lobbyists, a select few corporate litigants could take advantage of legislative history to a degree that rivaled that of the agencies. The emergent corps of lawyer-lobbyists was not so much an alternative to the administrative state as an outgrowth and adjunct of that state: as the great “Washington law firms” became fully established in the postwar era, they staffed themselves with veterans of the bureaucracy and acquired libraries of legislative history that imitated those of the agencies.

Part IV closes by considering the statist nature of legislative history through the eyes of Felix Frankfurter and Robert Jackson—progressive Justices who initially used legislative history with enthusiasm but then, by the late 1940s, worried that they might have created a monster. To Frankfurter, it seemed that lobbying and litigation—particularly when done by federal bureaucrats and their lawyers—were collapsing into each other in a way that advantaged governmental litigants and others with privileged access to the legislative process. To Jackson, judicial reliance on legislative history made litigation more of an “insider’s game,” privileging the bureaucratic state and the few law firms able to approach that level of administrative capacity. He warned that legislative history put “knowledge of the law practically out of reach of all except the Government and a few law offices.”38

***

More than twenty years ago, Peter Strauss wrote an illuminating essay suggesting that agencies are peculiarly competent to use legislative history when interpreting statutes.39 His argument has not been tested or developed by other scholars as much as it deserves to be,40 particularly the possibility that the use of legislative history in litigation—a deeply controversial practice—is something the government does more, and more effectively, than anybody else.41 This Article is the first study to confirm that possibility empirically and to flesh it out through primary research. I see this as part of the scholarly effort, recently begun by others, to map the largely unknown territory of administrative interpretation of statutes.42 I also see it as a response to the fervent call by Cass Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule for scholars of statutory interpretation to pay more attention to the varying institutional capacities of interpreters, particularly at the empirical level.43 In particular, I think the Article deepens our understanding of how the interpretive methods of agencies and of courts mutually constitute each other. The legal academy is accustomed to think that judges shape agencies’ methods,44 but this Article suggests that, at a crucial turning point in our history, it was more the other way round.

I. the timing of normalization

A. Quantitative Evidence

Here I set forth quantitative evidence that legislative history became a normal and routine interpretive source in federal statutory interpretation just around 1940. In tracing the process of normalization, I focus on the Supreme Court. Obviously the Supreme Court is only one part of a much larger federal judiciary, but my research and that of others has given me reason to think that the Court played a very dominant role in the federal judiciary’s shift toward legislative history—more dominant than in most other aspects of federal judicial practice.45

To discern the general shape of the Supreme Court’s transition toward routine reliance on legislative history, I begin by measuring the Court’s use of legislative history in every fifth year from 1900 through 1950. I use two metrics. I calculate both metrics by focusing, for a given calendar year, on all federal statutory cases decided by the Court in that year. I define a federal statutory case as one that was decided with a full, signed opinion and involved the interpretation of a federal statute. I count any case involving a federal constitutional challenge to a federal statute as falling within this category. Figure 1 gives the number of federal statutory cases in every fifth year from 1900 to 1950. The number fluctuates but almost always falls between 70 and 125.46

Figure 1.

federal statutory cases in the supreme court, 1900-50

Working within this universe of federal statutory cases, let us consider the two metrics of legislative history use. The first is the ratio, for a given year, between (1) the total number of legislative history citations in all opinions (majority and separate) in federal statutory cases and (2) the number of federal statutory cases. Figure 2 graphs this ratio for every fifth year from 1900 to 1950. It indicates a huge and lasting increase between 1935 and 1940. The lowest ratio after the break (in 1940) is 4.6 times the highest ratio before the break (in 1935). In general, the ratios before the break have their ups and downs, moving between zero (in 1905 and 1910) and 0.7 (in 1935); one might discern a vague, but hardly consistent, upward trend, at least before 1920. But that is minor compared to what happens between 1935 and 1940. There also appears to be a continuing upward trend after 1940, from 3.3 to 4.6, but the most striking feature is the initial jump in 1940.

Figure 2.

supreme court legislative history citations per statutory case, 1900-50

The second metric of legislative history usage is the percentage of federal statutory cases, for a given year, in which at least one opinion (majority or separate) contained at least one citation to legislative history. Figure 3 plots this percentage for the same years as in the preceding figure. Again, the most dramatic change is between 1935 and 1940, from 20% of the cases to 44%. This graph indicates a more pronounced (if not entirely consistent) upward trend prior to 1935 than Figure 2. But the real break occurs between 1935 and 1940.

Figure 3.

percentage of supreme court statutory cases citing legislative history, 1900-50

To get a closer look at the Court’s big transition, I now present the same two metrics, but this time for every year from 1930 through 1945. Figure 4 presents the number of federal statutory cases per year during that period. The number is fairly constant, always between 76 and 116.

Figure 4.

federal statutory cases in the supreme court, 1930-45

The first metric—legislative history citations per statutory case—exhibits a radical and permanent increase between the years 1939 and 1940. As plotted in Figure 5, this metric averages 0.9 for the years 1930-39, ending with a value of 1.2 in 1939. It then shoots up to 3.3 in 1940, and it averages 3.5 for the years 1940-45. In other words, the number of citations per case in 1940-45 was nearly quadruple the number in 1930-39. There is some fluctuation within both periods, but the highest value in 1930-39 (that of 1.7, in 1933) is still lower than the lowest value in 1940-45 (that of 2.2, in 1942).

Figure 5.

supreme court legislative history citations per statutory case, 1930-45

The second metric—the percentage of statutory cases containing at least some legislative history in at least one opinion—also exhibits a big increase leading up to 1940, though for this metric, the ramp-up begins slightly earlier. As plotted in Figure 6, the metric averages 22% for the years 1930-39, but it ends with a big uptick to 35% in 1939 (which is 11 percentage points higher than the next-highest year in 1930-39, that being 1934, at 24%). The percentage then shoots up to 44% in 1940, and it averages 45% for the years 1940-45. Thus, the average percentage for 1940-45 is more than double that for 1930-39. The lowest annual percentage in 1940-45 (that of 38%, in 1942) is still higher than the highest in 1930-39 (that of 35%, in 1939) and much higher than the next-highest percentage in 1930-39 (that of 24%, in 1934).

Figure 6.

percentage of supreme court statutory cases citing legislative history, 1930-45

Together, the metrics indicate a sudden break around 1940, perhaps beginning in 1939. The Court rapidly began to cite legislative history in more of its statutory cases and, in the cases where it did so, to cite it more copiously.47

The rise of legislative history occurred broadly across several areas of federal statutory law rather than being concentrated in any single area, or even any couple of areas. On this point, consider the 139 opinions (majority or separate) during 1940-45 that each contained five or more legislative history citations. These opinions, together, accounted for 79% of the legislative history citations during the period. Of these, the most numerous opinions were those involving labor (most commonly the Fair Labor Standards Act, plus the Wagner Act, Railway Labor Act, and others), but these accounted for only 17% of the opinions. The next-most prevalent area was tax, at 11%. Next, arguably, was national security (at 10%), but only if one cobbles together several different subjects that are really quite diverse, including military appropriations, bonuses and relief for soldiers, trading with the enemy, foreign agents, espionage, and internment. After that, the next-most prevalent areas were antitrust (7%), Indian law (6%), electricity and natural gas regulation (5%), bankruptcy (4%), communications regulation (4%), and transportation regulation (4%). Even these nine categories do not cover the remaining 32% of the opinions, which ranged broadly across public lands, food and drugs, agriculture, immigration and naturalization, and violent crime (kidnapping, bank robbery, etc.). One might say legislative history was associated with the “economic-regulatory” area, but that area encompassed most of the federal government’s responsibilities in the 1940s.48

The Court’s use of legislative history generally pertained to questions of “pure” statutory interpretation, unconnected to constitutional issues. To be sure, my definition of “statutory case” included all cases involving a constitutional challenge to a federal statute, but when I read all seventy of the Court’s cases containing at least one opinion with 10 or more citations to legislative history in 1940-45, I found only one case in which the legislative history pertained mainly to a constitutional issue.49

One may wonder if the increase in citations to legislative history truly reflected an increase in the relative importance of such material. Perhaps the Court simply began including more citations to all kinds of legal sources at this point in time? If that were true, the surge in legislative history would merely reflect a general surge in citations, not anything about legislative history itself.

I find this doubtful, largely because of the findings in a prior study by Nicholas Zeppos. Zeppos randomly selected twenty annual Terms of the Court from the period 1890 to 1990, which happened to include the 1944 Term, plus six Terms prior to 1944, the latest of those being 1932. He identified the federal statutory cases in all these Terms and, from that universe of cases, drew a random sample of 413 (about twenty per Term, on average). Zeppos’s team then counted, in each case, every source of authority cited in support of the decision (statutory texts, constitutional texts, cases, canons of construction, legislative history, treatises, etc.). He found that citations to legislative history—as a percentage of the total citations to all kinds of sources—exceeded 10% in 1944 but were below 2% in 1932 and in all previous Terms covered.50 This suggests that the big increase in legislative history that I find in 1940 was an increase relative to other sources.

Nor can the proliferation of legislative history be explained as a function of the proliferation of separate opinions during this period. To be sure, the 1940s did witness a large increase in the tendency of the Justices to write separately.51 And the proportion of legislative history citations appearing in majority opinions did fall. But the fall was not very big: from 86% in 1930-39 to 81% in 1940-45. Even if we focus solely on majority opinions and ignore all separate opinions, the number of legislative history citations per case is still 3.6 times greater in 1940-45 than in 1930-39, and the percentage of cases citing at least some legislative history is still more than double. The increase in separate opinions may have contributed to an “arms race,” in which the Justices piled up ever more citations to refute one another,52 but again, the Zeppos study indicates that legislative history grew in importance even relative to a more general increase in all kinds of citations. It should also be noted that the dramatic decline in unanimity began only in the winter of 1941-42,53 after the surge in legislative history was already quite evident.

B. Qualitative Evidence

Qualitative evidence confirms what the numbers suggest: legislative history went from obscure to routine around 1940. Observers who lived through the period noted the change. Berkeley professor Max Radin, commenting on the Supreme Court in 1945, referred to “the now orthodox procedure of examining the legislative history.”54 Harvard professor Archibald Cox wrote in 1947:

Whereas formerly the [federal] courts, shut off from reliable indicia of the legislative intent, sometimes substituted their own conceptions of sound policy, they are now so overwhelmed by arguments from legislative history that the problem has become one of managing the mass of materials available and winnowing out the unreliable.55

Justice Robert H. Jackson announced in 1948 that the “custom of remaking statutes to fit their histories has gone so far that a formal Act . . . is no longer a safe basis on which a lawyer may advise his client or a lower Court decide a case.”56 A 1952 Columbia Law Review note observed that since 1940, “the use of legislative history in the interpretation of statutes has become standard practice in the federal courts.”57 In their classic The Legal Process (1958), Harvard professors Henry Hart and Albert Sacks noted that—over “the last fifteen years” and particularly since a key 1940 decision which I shall discuss below—there had been a “sudden efflorescence of citations of legislative materials in [Supreme Court] briefs and opinions,” providing the Justices with a “mass of available material” so large that they could not fully process it all.58

This chronology is further confirmed in the writings of Elizabeth Finley, the era’s best-known expert on legislative history research. From 1921 to 1942, she was the librarian of Root, Clark, Buckner, and Ballantine, a top Wall Street firm.59 In 1943, she became the librarian of Covington, Burling, Rublee, Acheson, and Shorb, which was then the largest firm in Washington, D.C.60 She and another woman, hired that same year at another D.C. firm, may have been the first private-firm librarians in the nation’s capital.61 In the course of twenty years at Covington, Finley would become the first private-firm librarian ever to be president of the Association of American Law Libraries (AALL).62 In particular, she became “[w]ithout question, . . . the leading national authority on the ways and means of collecting and compiling U.S. legislative history.”63

Finley’s writings indicate that legislative history emerged from obscurity around the late 1930s or early 1940s. Giving a paper at the AALL conference in 1946, she said:

Something new has been added to our profession, and whether we like it or not, it appears to be here to stay. I speak as the practicing lawyer’s librarian. . . . [F]rom the practical angle, I assure you the most frequent request these days is “Can you give me the legislative history of this act.”64

When How to Find the Law added a chapter on legislative history in its fourth edition of 1949, Finley wrote it and opened by saying: “Probably the most startling development in legal research within the past fifteen years, and certainly one with the least literature, has been the increasing importance of legislative histories.”65 In a 1959 essay, she noted that “many law libraries” had been compiling scrapbooks of legislative history for particular statutes for “the past twenty years,” adding that “only in rare cases will you discover a compiled history of any federal law more than twenty-five years old.”66 She also referred to a certain statute that had been “passed in 1920, long before legislative histories were being cited extensively.”67 Having been a big-firm librarian since 1921, Finley knew what she was talking about.

Consistent with this, legal research guides began paying serious attention to legislative history only in the 1940s. In 1926, the fifth and final edition of Roger W. Cooley’s standard work, Brief Making and the Use of Law Books, said nothing about how to research legislative history and devoted only two sentences specifically to such material (plus three other sentences of more general discussion about extrinsic evidence of historical context).68To gauge the treatment of legislative history in subsequent works of this kind, I located all major legal research guides that went through two or more editions from 1930 through 1950.69 Of the five guides in this category, four discussed legislative history for the first time (or went beyond negligible discussion for the first time) in their first post-1940 editions.70

In the same vein, the years 1943-46 saw three big institutional initiatives aimed at routinizing the use of legislative history, likely in reaction to the Supreme Court surge that began in 1940. One of these came in December 1943—near the end of the fourth and (as yet) biggest year of the Court’s post-1940 surge—when Chief Justice Harlan F. Stone wrote to Archibald MacLeish, the Librarian of Congress. Stone had learned that the Library of Congress had a “spare” copy of the U.S. Congressional Serial Set, which then ran to 10,000 volumes. Stone wanted MacLeish to transfer the “spare” 10,000 volumes to the Supreme Court’s own library. “We often have occasion to use the Congressional Serials in looking up matters of legislative history,” explained Stone, “and it would be of great assistance” if the spare set “could be placed in our Library where it would be available at any time to the members of the Court.”71 MacLeish agreed,72 and these 10,000 volumes became, de facto, part of the Court’s permanent collection.73

Another institutional initiative came from the nation’s leading law publisher, West. In 1941, the company inaugurated the U.S. Code Congressional Service, a regular series of pamphlets (consolidated at the end of each year into a hardbound volume) containing the latest congressional acts and federal agency regulations, plus small selections of legislative history, scattered throughout. But then, in 1943, the Service began paying much more attention to legislative history: 329 pages’ worth during that year (consisting of a few selected documents on each major statute), with its own dedicated section of the annual volume.74

The third institutional initiative that occurred in apparent response to the Court’s surge came from the Law Librarians’ Society of the District of Columbia. Because so few D.C. law firms had librarians in the mid-1940s, the Society consisted mostly of federal agency librarians.75 These librarians had, over the preceding years, compiled a large number of what I call “scrapbook” legislative histories—books compiled by hand that each pertained to a specific statute, often with an index. For lawyers specializing in the implementation of one or a few statutes, such scrapbooks were far more useful and economical than having to rely on whole runs of the Serial Set or Congressional Record. Compiling even one scrapbook took much time and research, making it a precious item when complete.76 The federal agency librarians realized they collectively held a plethora of such scrapbooks, and knew that such histories were “more and more frequently referred to by courts and lawyers.”77 They therefore formed a committee in 1946 to assemble and publish a “Union List of Legislative Histories.”78 From its nucleus in D.C.-based federal agencies, this list would gradually expand in subsequent editions (there have now been seven, the most recent in 2000).79

Consistent with the idea that use of legislative history became normal in the 1940s, the practice began, in those years, to attract a new kind of criticism. For the first time, people began to speak of using legislative history as a dominant practice that was going too far. Frankfurter in 1947 mentioned “the quip that only when legislative history is doubtful do you go to [the text of] the statute.”80 Jackson, having enthusiastically used such material in the early 1940s, reversed himself in 1948: “I am coming to think it is a badly overdone practice . . . .”81 In 1948, Charles Curtis, the popular legal writer, recalled that the “courts used to be fastidious as to where they looked for the legislative intention,” but now they were “fumbling about in the ashcans of the legislative process for the shoddiest unenacted expressions of intention.”82 The first of several editions of Effective Appellate Advocacy concluded in 1950 that the surge of legislative history over the last decade had caused lawyers “infinite grief.”83

II. explaining normalization: new justices with new ideas

The rise of legislative history was caused in part by a rapid turnover in the personnel and therefore the ideology of the Court. I devote this part to explaining how the appointment of new progressive-minded Justices by President Roosevelt helped bring about normalization (before turning to the other major driving force—the administrative state—in Part III).

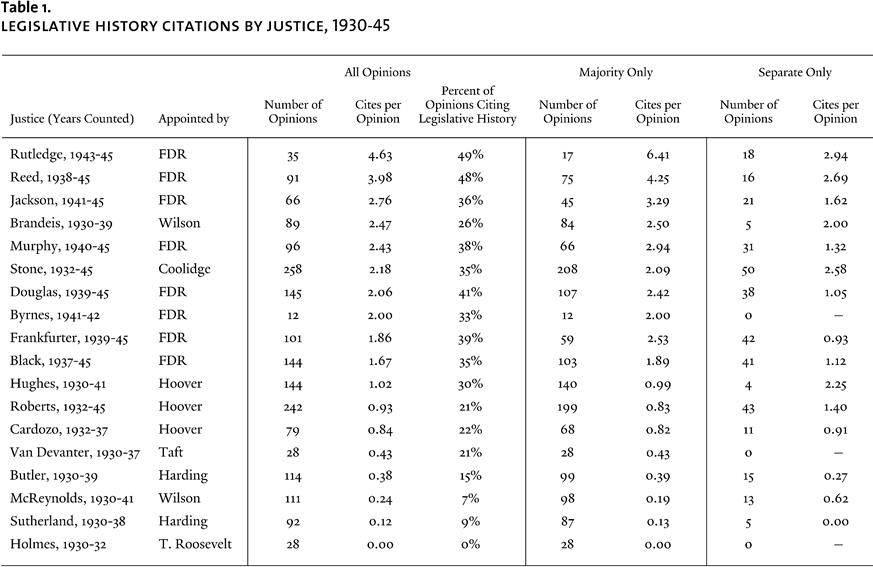

To appreciate the ideological turnover and its connection to legislative history, consider Table 1. It includes every Justice who wrote more than three opinions in federal statutory cases in 1930-45. It lists, for each Justice, the number of legislative history citations per opinion in federal statutory cases during that period, the percentage of the Justice’s opinions that contained any legislative history, and a breakdown of the citation/opinion ratio as between majority and separate opinions. The Justices are listed in descending order of their citation/opinion ratio for all opinions (which roughly correlates with the percentage of each Justice’s opinions that contained any legislative history).84

As Table 1 demonstrates, there is a strong correlation between the likelihood that a given Justice would cite legislative history and his association with progressive ideology and President Roosevelt. Of the nine Justices in the top half of the order, seven were appointed by Roosevelt (in 1937-43) and the other two, Brandeis and Stone, had reputations as leading progressives on the pre-Roosevelt Court.85 Of the nine Justices in the bottom half, eight had joined the Court before Roosevelt took office in 1933. Those eight include all of the “Four Horsemen” (the Justices who voted most frequently to undermine the New Deal) and the moderates Hughes and Roberts (who sometimes voted against the New Deal). The Four Horsemen and Hughes all left the Court in 1937-41.

Further evidence of the connection between progressive ideology and legislative history appears in United States v. American Trucking Ass’ns,86 decided in May 1940, near the very start of the surge. In that case, Roosevelt’s appointees formed a five-to-four majority for an opinion expressing great openness to legislative material. In fact, some commentators have briefly suggested that American Trucking played something like a causal role in the rise of legislative history.87 A close examination of the opinion is thus warranted to determine its exact place in the process.

First, some background: in Anglo-American statutory interpretation, there had long been a maxim known as the “plain meaning rule,” which said that a judge ought to follow statutory text that was unambiguous on its face. The rule had originated as a counter to the ancient idea of equitable interpretation,88 but after Holy Trinity in 1892, some U.S. federal judges repurposed it as an instrument to limit the use of legislative history: in the updated formulation, legislative history was inadmissible if the text was facially clear.89 From the 1890s to the 1930s, the Court had sometimes applied the plain meaning rule and sometimes ignored it.90

The plain meaning rule was at the center of controversy in American Trucking. In 1935, Congress passed the Motor Carrier Act (MCA), which brought the trucking companies under the regulation of the industry-friendly Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC).91 The MCA empowered the ICC to set maximum hours for “employees” of the trucking companies. But the ICC construed this power to cover only safety-related employees (such as drivers), not all employees. This became a high-stakes matter in 1938, when Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), empowering the Department of Labor (DOL), which was not industry-friendly, to set maximum hours for all industrial employees with an exception for those already covered by the MCA. The trucking companies, hoping to escape the FLSA, argued that the MCA meant to cover all their employees. DOL disagreed (as did the ICC, which wanted to stick to its core competence of regulating safety).

The lower court held that the word “employees” unambiguously covered all the trucking companies’ employees and refused to consider legislative history indicating that the provision was aimed at preserving safety.92 But the Supreme Court sided with the government, five-to-four, with the five Roosevelt appointees in the majority and the four pre-Roosevelt Justices in the minority.93 Justice Reed, writing for the majority, selectively read the Court’s prior cases so as to effectively repudiate the plain meaning rule:

When [the text’s] meaning has led to absurd or futile results, . . . this Court has looked beyond the words to the purpose of the act. Frequently, . . . even when the plain meaning did not produce absurd results but merely an unreasonable one “plainly at variance with the policy of the legislation as a whole” this Court has followed that purpose, rather than the literal words. When aid to construction of the meaning of words, as used in the statute, is available, there certainly can be no “rule of law” which forbids its use, however clear the words may appear on “superficial examination.”94

The four dissenters wrote no opinion but simply endorsed “the reasons stated” by the lower court.95

Reed’s pronouncement in American Trucking was significant, but I do not think it predetermined the surge in legislative history that occurred over the next few years. Neither before 1940, nor since, has the Supreme Court treated statements on statutory interpretation methodology as having much precedential value. In the years up to 1940, the Justices, progressive and conservative alike, had been quite inconsistent in their adherence to the plain meaning rule.96 They had also been inconsistent on other methodological points regarding legislative history, such as the admissibility of floor debates.97 Likewise, in the first several years after 1940, the Court did not follow “consistently accepted principles of interpretation,”98 and this casualness about method encompassed legislative history.99 As Hart and Sacks wrote in the 1950s, American Trucking “was decided by a closely divided Court, and no one could then [in 1940] have been sure” that its statement about the universal admissibility of legislative history “really meant what it said.”100

Still, even if American Trucking did not control the Court’s post-1940 interpretive practice as a matter of precedent, it did reflect the tendency of progressive judges to be receptive to legislative history. That tendency makes sense in light of the progressive legal thought of the period.

The bête noire of progressive legal thinkers—such as Oliver Wendell Holmes, Louis Brandeis, Robert Hale, and Karl Llewellyn—was the classical notion that common-law doctrines in fields like property and contract were neutral and apolitical. Such doctrines, according to the progressive critique, were not determinate enough to decide particular cases. When judges claimed to make decisions on the basis of these doctrines, they in fact exercised discretion and made policy choices under a cloak of neutrality. Judges, counseled the progressives, ought to be explicit about the policy choices that inevitably underlay their decisions. Conscious, transparent articulation of the policies behind the common law was the best way to ensure the wise resolution of disputes. Although absolute determinacy was impossible, explicit policy reasoning would bring legal decisions nearer to that ideal than would the empty verbal formulas of doctrine.101

Because they did not revere common-law rights of property and contract as neutral and apolitical, progressives were receptive to regulatory and social-welfare legislation. But progressive scholars who studied legislation—such as James Landis and Frederick de Sloovère—found that judicial interpretation of statutes often exhibited pathologies similar to those of conventional common-law reasoning. In particular, judges often made a pretense of reasoning in a neutral and objective manner from the statute’s literal words, without reference to its policies. This often had the effect of undermining the legislature’s policy choices and substituting the judge’s own, under the cloak of literalism. By the early to mid-1930s, Landis, de Sloovère, and other scholars were pushing legislative history as an interpretive tool to ensure that judges would consciously confront legislators’ intent, rather than hide behind the false determinacy and objectivity of the text (as they did when invoking the plain meaning rule).102 But here the progressives ran into a problem: the charge of indeterminacy that they leveled against common-law doctrinal reasoning and statutory text-reading could also apply to the process of discerning the legislature’s “intent.”103

As William Eskridge shows, several progressive scholars of statutory interpretation in the late 1930s and 1940s converged on an answer to this question. They began by conceding that statutory interpretation, even if couched as the search for legislative intent, frequently required the judge to make discretionary choices.104 But they insisted that the judge could productively cooperate with the legislature by (1) seeking, in good faith, to identify the legislation’s overall objective and (2) making discretionary choices in a way that creatively furthered that objective.

The practical implication of this new thinking, as Eskridge points out, was that judges should reason from legislative history at a relatively high level of generality. Legislative history was a source from which the judge could infer the overall objective—the general intent—of the legislation. Having gleaned the general intent from the legislative material, the judge would then reason “downward” to figure out how best to achieve that objective on the specific facts of the case. This approach contrasted with an older academic conception of legislative history as useful for discerning the legislature’s specific intent—that is, the exact result the legislature would have wanted on the particular issue presented to the court, without reference to the statute’s larger objective or to the implementational creativity of the judge.105

The focus on general intent reached its culmination in Hart and Sacks’s 1958 classic The Legal Process.106 In their view, judges should use legislative history only insofar as it spoke to general intent, and general intent should be defined to include only rational, public-regarding goals. Since legislators’ duty was “to think in general terms,” the “probative force of materials from the internal legislative history of a statute varies in proportion to the generality of its bearing upon the purpose of the statute or provision in question.”107 If a congressman predicted in the legislative record that the bill would produce a certain result when applied to a certain situation, then a judge facing that situation should not automatically impose that result. Instead the prediction “should be given weight only to the extent that [it] fits rationally with other indicia of general purpose.”108 The judge was to attribute a public-regarding rationality to the legislature and take account of legislative history only insofar as it fit into that vision of rationality. Although “a court should try to put itself in imagination in the position of the legislature which enacted the measure,” it “should not do this in the mood of a cynical political observer, taking account of all the short-run currents of political expedience that swirl around any legislative session.”109 Rather the court “should assume, unless the contrary unmistakably appears, that the legislature was made up of reasonable persons pursuing reasonable purposes reasonably.”110 As Richard Posner later observed, Hart and Sacks apparently believed “that the judge should ignore interest groups, popular ignorance and prejudices, and other things that deflect legislators from the single-minded pursuit of the public interest as the judge would conceive it.”111 Hart and Sacks exhibited “a reluctance to recognize that many statutes are the product of compromise between opposing groups.”112

How much can the Court’s surge in legislative history during the early 1940s be understood as a manifestation of the interpretive theory that was just then emerging in progressive academic circles (and later reached its culmination in The Legal Process)? Arguably, the general-intent theory required an especially comprehensive analysis of legislative history, which would perhaps increase the rate of citation.113

There is surely an important connection between the theoretical developments and the surge, though not so strong as to provide a complete explanation for the latter. With the exception of a very short article by Landis in 1930,114 the earliest (and, until after World War II, the clearest) articulation of general-intent theory came from Harry Willmer Jones, in a series of three articles published in 1939-40.115 At the time, Jones was a young lecturer at Columbia and would start a professorship at Berkeley in 1940.116 Only the first of his three articles was published before May 1940; it was cited in Reed’s American Trucking opinion, while his other two articles were not.117 The first of Jones’s articles (the one cited by Reed) documented the Court’s frequent failure to adhere to the plain meaning rule and argued that textual meaning could never be plain without context, but it said almost nothing about using legislative history to discern general intent—a theme that Jones would elaborate only in the second and third articles. Consistent with this, American Trucking itself was hardly a learned treatise on general intent. It discussed interpretive methodology only briefly, quoting a 1922 opinion about the need to honor “the policy of the legislation as a whole” but saying nothing more about general intent.118

Hart and Sacks in The Legal Process briefly noted the surge in legislative history that followed American Trucking, but—significantly—they believed the surge had occurred without much of a theory behind it. Amid the “sudden efflorescence of citations of legislative materials in briefs and opinions” in the years after American Trucking, neither the Justices nor the lawyers “had a sufficiently articulated and disciplined theory of interpretation to know how to appraise the mass of available material properly and prevent abuses.”119

To be sure, there were many opinions in 1940-45 that used legislative history to discern intent at a high level of generality, then reasoned downward to the meaning of specific provisions.120 These opinions indicate that the emergent theory of general intent played some practical role in the surge. For example, in a 1943 case on whether a federal statute exempted Indian lands from state taxation, the state invoked the remarks of the bill’s sponsor, but Justice Murphy, writing for the Court, declared that, even if those remarks did support the state’s interpretation, “we do not accept them as definitive,” for they were “opposed to” other indicia of the act’s meaning, including “the reasons for its enactment,” as evidenced by the committee reports describing “the problem at which the . . . Act was aimed.”121 Similarly, in a 1945 case on whether the FLSA allowed backpay claimants to settle their suits, Reed wrote for the Court that

[n]either the statutory language, the legislative reports nor the debates indicates that the question at issue was specifically considered and resolved by Congress. In the absence of evidence of specific Congressional intent, it becomes necessary to resort to a broader consideration of the legislative policy behind this provision as evidenced by its legislative history and the provisions in and structure of the Act.122

Several other opinions followed this pattern.123

But at the same time—in keeping with Hart and Sacks’s view that the surge in legislative history did not conform to a particular theory—there were also many opinions that used such material to discern legislative intent at a high level of specificity, without self-consciously elaborating a public-regarding policy. The persistence of this approach is consistent with the intellectual history told by Eskridge, who traces the interest in general intent at the academic-intellectual level and notes its resonance with American Trucking but adds that the older interest in specific intent survived and coexisted with the new thinking.124 For instance, in 1941, when deciding whether the Chandler Act of 1938 repealed an emergency 1933 statute establishing a broad definition of “farmer” for the purpose of certain bankruptcy protections, Murphy wrote an opinion for the Court citing copious legislative history indicating congressmen’s intention to leave the 1933 provision alone, with virtually no policy discussion.125 As another example, Reed in 1943 wrote an opinion for the Court holding that the statutory provisions on extra compensation for customs inspectors covered work at night but not Sundays and holidays. He cited a mountain of legislative history about the understandings of various congressmen and stakeholders but without weaving them into any broader purposive thinking.126 Several more opinions took this approach in using legislative history.127

At times, a single opinion relied upon legislative history both to discern general intent and to confirm the correctness of the specific application. Thus, Frankfurter in 1941 wrote that the Wagner Act’s purpose (evident from its legislative history) was to encourage worker self-organization for industrial peace, and he concluded that this purpose required the Court to read the Act’s anti-discrimination provision to cover not only firing but also hiring. But he also added that a committee report contemplated this exact application.128 In 1943, Black wrote an opinion giving a very broad reading to Congress’s 1939 abolition of assumption of risk under the Federal Employers’ Liability Act, basing his conclusion both on the enactment’s general policy and on the fact that congressmen during the hearings had criticized a particular case (whose holding, the opinion therefore reasoned, the statute must be read to override).129 In 1944, the Carolene Products Company argued that its milk compounds did not come within a statutory ban on products “in imitation or semblance of milk,” since the act (said the Company) required the imitation to be deliberate. The Court, per Reed, rejected this argument because the committee reports named specific products that were meant to be covered, which included “compounds of this innocent character.” Having said this, Reed could not resist adding that Carolene Products’ own “compounds were themselves so named.”130

The absence of a simple causal relationship between general-intent thinking and the surge in legislative history is especially evident in two further cases: Viereck v. United States (1943) and Gemsco, Inc. v. Walling (1945). In Viereck, the Court had to decide whether a statute requiring a foreign agent to disclose propaganda activities encompassed situations in which the agent spread propaganda on his own behalf, rather than on behalf of his foreign principals. On the basis of legislative history, Black argued that because the “general intent of the Act was to prevent secrecy as to any kind of political propaganda activity by foreign agents,” the act should be read broadly.131 But Black commanded only one additional vote for his position.132 Opposing him and writing for the majority was Stone, who acknowledged Black’s argument (and the government’s) that the act, if not read broadly, would be a “halfway measure.” But Stone marshaled post-enactment legislative history to show that “Congress itself . . . recognized that the legislation was in this sense a halfway measure.”133 Further, Stone (who showed himself capable of reasoning about general intent elsewhere134) expressed anxiety about this method:

While Congress undoubtedly had a general purpose to regulate agents of foreign principals . . . we cannot add to [the Act’s] provisions other requirements merely because we think they might more successfully have effectuated that purpose. And we find nothing in the legislative history of the Act to indicate that anyone concerned in its adoption had any thought of [the application urged by the government].135

Here, Stone gathered his own history to counter Black’s history-based invocation of general intent.

In Gemsco, the Court faced the question of whether the FLSA authorized the DOL to ban home-work across the entire embroideries industry if the agency concluded that doing so was necessary to enforce the minimum wage in that industry. Employers cited copious legislative history implying a political deal not to ban home-work outright, but Rutledge, writing for the Court, cast the history as ambiguous and insisted that, in any event, the industry’s reading would “deprive the [DOL] of the only means available to make [the statute’s] mandate effective” and “would make the statute a dead letter for this industry.”136 The “necessity to avoid self-nullification” was enough to refute the industry’s reading.137 In this case, legislative history was the enemy of general intent.

The Justices, when using legislative history, did not confine themselves to an idealized, rational vision of the legislature. On the contrary, they could, at times, be brutally frank about the realities of Congress. This was most true of Black, the former U.S. Senator. In one opinion, he emphasized that a certain interpretation of a bill had been “accepted both by the unions and the railroads” at the hearings.138 In another opinion, he pointed out that a federal statute alleged to override Oklahoma state taxes had been “sponsored by Oklahoma Congressmen who said nothing which supports the imputation that they intended to deprive their State of this income.”139 In a third, concerning the ICC’s treatment of railroad and barge lines, he fulminated that the “railway-minded” ICC was taking the very anti-barge actions that senators “from the midwestern states where the barge lines . . . were operating” had feared it would take—and which the statute’s cheerleaders had assured them it could not take.140 Similarly Reed, in a case about an excise tax on the processing of imported oils, based his reading on the special-interest nature of the statute: “the legislative history cannot be read without reaching a conviction that the advantages which would result to American vegetable oil producers from the heavy tax on oils not produced in the continental United States played a leading part in promoting the legislation.”141 For his part, Roberts argued that one of the provisions of the Federal Power Act, having been amended to meet the demands of state regulators, should not be construed to encroach on their turf.142 Frankfurter, in one instance, pointed out the unusually long “continuity of membership” on the House and Senate Commerce Committees, and he suggested the Court should assume that bills from those committees contained “skilled language” whose variation from other relevant statutes must be meaningful (apparently implying that other committees were less “skilled”).143

All in all, the coincidence between Roosevelt’s appointments and the surge in legislative history—combined with the intellectual resonance between progressive legal thought and legislative history—indicates that the ideologically-charged turnover of the Justices was surely a cause of the normalization of this interpretive source. Yet the turnover is not a complete explanation. We know it is incomplete because of the tensions (just discussed) between the emergent progressive legal theory of legislative history and the Justices’ actual use of that material.

And we know it is incomplete for another reason: even the pre-Roosevelt Justices (the dissenters in American Trucking) greatly increased their use of legislative history in the 1940s. On this point, consider the examples of two Justices who joined the Court well before 1940 and served till well after 1940: the progressive Harlan F. Stone and the moderate Owen Roberts. In the years 1930-39, Stone had a citation/opinion ratio of 1.5, but in 1940-45, it was double that (3.0). Similarly, Roberts in 1932-39 had a ratio of 0.5, but in 1940-45, it was more than double (1.4). A similar pattern obtains for the moderate Hughes: his ratio grew from 0.9 in 1930-39 to 1.7 in 1940-41 (though we should not assign too much weight to this, since Hughes’s track record in 1940-41 was short). The two early Roosevelt appointees who acquired more-than-negligible track records during the 1930s also exhibited a big increase in their citation rates in 1940 and later. Black in 1937-39 had a citation/opinion ratio of 0.8, which more than doubled to 1.9 in 1940-45. Reed in 1938-39 had a ratio of 0.9, which quintupled to 4.7 in 1940-45. The experiences of all these Justices suggest that we cannot explain the transformation simply by saying that (1) progressive Justices were more inclined to cite legislative history and (2) Roosevelt appointed more progressive Justices. Something more was happening.

III. explaining normalization: the new administrative state

The progressive ideology of the Roosevelt appointees was a major but not sufficient cause of the interpretive revolution. Its insufficiency, as noted above, is evident from the tensions between progressive theory and judicial practice and from the pre-Roosevelt Justices’ change in behavior.