Election Day Registration and the Limits of Litigation

abstract. The most significant reform mandated by The For the People Act of 2019 (H.R. 1) is Election Day registration (EDR), which allows eligible voters to register to vote and cast a ballot at the same time on Election Day, effectively eliminating any earlier registration deadlines. The sum total of social-science evidence indicates that EDR is the single registration or voting reform that would do the most to improve the United States’ comparatively low turnout rates. Legislative reform efforts around EDR have been very successful in recent years, as the number of states with EDR has more than doubled over the last decade. The corollary to the observation that EDR boosts turnout, however, is that voter registration deadlines do much to suppress it. Given that voting-rights advocates have achieved some litigation successes fighting relatively new laws and practices that make registration and voting more difficult—such as strict voter ID requirements—one might rightfully wonder whether they could leverage similar strategies to challenge voter-registration deadlines. In fact, such litigation has been tried, but it has not yet been successful. This may seem somewhat surprising, given that social scientists are more certain about voter-registration deadlines’ suppressive effect on turnout than they are about newer restrictions like strict voter ID requirements. In any event, given the relative success of legislative reform efforts around EDR (at least in comparison to litigation), the more promising path at present for making EDR a national standard is federal legislation.

Introduction

The For the People Act of 2019 (H.R. 1)1 mandates a number of important registration and voting reforms. Perhaps the most significant is a requirement that states offer Election Day registration (EDR), which allows eligible voters to register to vote and cast a ballot at the same time on Election Day, effectively eliminating any earlier registration deadlines. Political scientists generally agree that EDR boosts turnout significantly; indeed, there is broader consensus among social scientists about the effect of EDR on turnout than there is with respect to any other voting reform.2

The corollary to the observation that EDR substantially increases turnout is that voter registration deadlines do much to suppress it. That is, the requirement that voters register by a certain date in advance of an election keeps many otherwise-eligible voters from participating, simply due to a failure to complete paperwork by an arbitrary deadline. Given that voting-rights advocates have recently achieved some litigation successes fighting relatively new laws and practices that make registration and voting more difficult, such as strict voter ID requirements, one might rightfully wonder whether they could leverage similar strategies to challenge voter-registration deadlines. In fact, such litigation has been tried, but it has not yet been successful.

Part I of this Essay describes EDR, including evidence of its effect on voter turnout and its increasing popularity around the country. The sum total of social-science evidence indicates that EDR is the registration or voting reform that, standing alone, would do the most to improve the United States’ comparatively low turnout rates. Legislative reform efforts around EDR have been very successful in recent years, as the number of states with EDR has more than doubled over the last decade.

Part II reviews federal and state litigation challenging voter-registration deadlines, which has not yet succeeded in establishing EDR in any state. This stands in stark contrast to litigation against newer voter-suppression tactics, which has found at least some success in recent years. This divergence may seem somewhat surprising, given that social scientists are more certain about voter-registration deadlines’ suppressive effect on turnout than they are about newer restrictions like strict voter ID requirements. Given the relative success of legislative reform efforts around EDR (at least in comparison to litigation), the most promising path at present for making EDR a national standard is federal legislation, whether H.R. 1 or a standalone EDR mandate.

I. election day registration and voter participation

EDR is perhaps the single legal reform that could do the most to improve our voter-turnout rates, which are dismally low compared to those of most economically developed democracies. The Pew Research Center estimates that turnout in the 2016 presidential election was approximately fifty-six percent, which places the United States at twenty-sixth out of thirty-two countries within the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.3 While the legal regime governing voting and registration is obviously not the sole (or even necessarily the most significant) factor affecting total turnout,4 changes to the legal regime that reduce the “cost” of voting5—that is, the burdens borne by potential voters in registering or casting a ballot—can facilitate voter participation.6

A number of affirmative voting reforms have thus been the subject of increasingly active advocacy efforts. These include early voting (to eliminate the burden of making time to vote on a particular day); no-excuse mail-in absentee voting (to eliminate the burden of traveling to a polling place); online registration (to eliminate the inconvenience of using paper registration forms); same-day registration (to permit voters to register and cast a ballot in a single trip to a polling location, during early voting and/or on Election Day itself, usually subject to heightened documentation requirements); EDR (same-day registration on Election Day, effectively eliminating the requirement that voters register by some set deadline before Election Day); and automatic registration (to eliminate the burden of registering altogether). These various reforms are becoming increasingly popular. In 2018 alone, eight states adopted one or more of them.7 H.R. 1 seeks to nationalize all of these reforms (and others), requiring states to adopt them for all federal elections.

In some ways, however, EDR is nothing new. For roughly the first century of this country’s existence, almost all states allowed eligible voters to simply present themselves on Election Day and cast a ballot. Most states did not have any formal voter registration at all until the period between the 1870s and World War I, an era that saw a wide range of efforts to “purify” the electorate, often “inspired by partisan interests, enacted to influence the outcome of elections.”8 These laws generally fulfilled their discriminatory intent, as it was often the case that “the passage of new registration laws in the early twentieth century was immediately followed by a sharp plunge in turnout, particularly in the cities,” with “a disproportionate impact on poor, foreign-born, uneducated, or mobile voters.”9

After the popularization of voter registration, the 1970s saw a first wave of states revert to a simplified process by adopting a formal system of EDR (Maine, Minnesota, and Wisconsin).10 Starting in the early 1990s, political-science research has consistently found a statistically significant relationship between EDR and turnout, ranging from an increase of two percentage points to double-digits.11 While measuring the effect of laws on turnout is a tricky business, there is little serious debate remaining among social scientists regarding EDR: the sum total of empirical research on EDR—in terms of both the balance of individual studies12 and meta-analyses aggregating data from individual studies13—points to a significant positive effect of EDR on turnout. Moreover, some studies suggest that EDR has particularly significant turnout effects among historically low-turnout or disenfranchised groups like young, low-income, and African American voters.14

Anecdotal evidence from the record-setting 2018 midterm elections, while not dispositive, points in the same direction.15 In 2018, the four states with the highest turnout, and seven of the top ten, had EDR.16 Overall, EDR states’ turnout rate (56%) was seven percentage points higher than that of non-EDR states (47%).17 And while several of these states had noteworthy competitive elections (for example, a high-profile gubernatorial election in Wisconsin), overall, states with competitive elections in 2018 saw a more modest two-percentage-point turnout advantage over states without competitive elections.18 In other words, while competitiveness was a factor, it may not have been the sole or even primary determinant of higher turnout in EDR states.

There are several reasons why EDR may have a positive effect on turnout. As a simple logistical matter, allowing registration and voting on the same day reduces the administrative cost of voting, by simplifying a two-step transaction (which requires knowledge of advance registration processes and deadlines) into a single trip to a polling location. EDR also allows voters to update or correct their registrations on Election Day, which enables those who may have recently moved to vote without having to re-register in advance of the election.19 Also, some voters are erroneously purged20 or left off the rolls due to administrative error, and EDR allows these voters to correct their registration information on Election Day, ensuring that they are not disenfranchised.21

Perhaps most significantly, allowing registration once voting has commenced—either during early voting or on Election Day—takes advantage of voter interest when it is at its highest. Research by Alex Street and others regarding the correlation between internet searches for voter registration and voter-registration activity provides some real-time evidence supporting this hypothesis.22 Generally, voter-registration activity tracks the level of internet searches for voter registration, increasing as Election Day approaches. But after a state’s voter-registration deadline passes, registration plummets (presumably because registration becomes a futile act for those interested in the upcoming election), even as internet searches for voter registration continue to surge.23 Street’s research suggests that increased interest in voter registration as Election Day nears is tied to heightened activity at the end of the campaign period.24 This, in turn, implies that a state can boost participation by simply shortening the registration blackout period between its registration deadline and Election Day, thereby permitting voters to register later as interest increases. Street and his colleagues conclude that permitting registration on Election Day itself would boost turnout by approximately three to four million voters nationally in a presidential election.25

Indeed, social-science evidence is clearer as to the suppressive effect of voter-registration deadlines on aggregate turnout levels than it is with respect to newer, more high-profile obstacles, like voter ID laws. Statistical analyses of turnout estimates among states26 and studies of administrative records of voters actually barred from voting under a strict ID regime27 provide some evidence as to the suppressive effect of voter ID laws, but they are mixed. Such studies are, of course, limited in various important ways: administrative records concerning ballots rejected due to lack of photo ID cannot account for voters deterred from going to the polls or casting a ballot due to the ID requirement;28 meanwhile, statistical estimates of turnout based on sample surveys are imprecise, with margins of sampling error that are probably too large to detect the plausible effects of voter ID requirements.29

That is not to suggest newer voter-suppression laws are not a significant problem: separate and apart from turnout statistics, there is a “solid consensus” among social scientists that there are racial disparities regarding the possession of government-issued photo ID.30 And in state after state, individuals have been locked out from the ballot because of their inability to comply with new documentation or identification requirements.31 But the fact remains that there is at least more empirical clarity as to the suppressive effect of advance voter-registration deadlines on overall turnout levels than there is for voter ID laws. Reformers aimed at improving turnout should, accordingly, view shorter voter-registration deadlines and Election Day Registration as important goals.

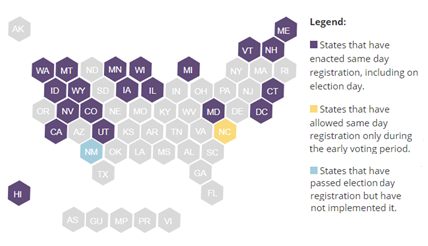

Twenty-one states and the District of Columbia have already enacted some form of same-day registration, as set forth on the following map from the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL):

Figure 1. States with Same Day and Election Day Registration32

|

II. the limits of litigation challenging voter-registration deadlines

If EDR is the single most important registration reform that we could implement today, can litigation serve as an effective vehicle for making it a national standard? The old saying is that, to a hammer, everything looks like a nail. To a civil-rights litigator, every problem can seem like a lawsuit waiting to be filed. When it comes to EDR, however, litigation has been unsuccessful to date—a result that, at first blush, may seem surprising given the relative success of litigation challenging barriers such as strict ID laws, and the fact that registration deadlines may have a more significant effect on voter participation. Indeed, the problem here has not been a lack of effort or of a cogent legal theory. Rather, the failure of lawsuits challenging registration deadlines thus far likely speaks to the practical limitations of courts as vehicles for affirmative reform, and counsels a strategy that focuses primarily on legislative efforts to establish EDR, like H.R. 1.

Overall, election-related litigation has exploded since 2000,36 and its growth has accelerated in the last ten years.37 This is largely a response to the fact that “more voting restrictions have been enacted over the last decade than at any point since the end of Jim Crow,”38 resulting in a wave of litigation against these voter-suppression tactics. As I have argued elsewhere,39 this spike in “vote denial” practices is partly a consequence of the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder,40terminating the federal preclearance regime which, for decades, had required states and counties with the worst histories of discrimination to obtain federal approval before making changes to their voting laws.

Despite some failures—such as a Supreme Court decision upholding Ohio’s voter purges,41 and seven-plus years of litigation that thus far have failed to dislodge Wisconsin’s voter ID law42—there have been several notable successes. For example, civil rights litigators have successfully challenged: a sweeping omnibus bill in North Carolina that, among other things, imposed a strict voter ID requirement, cut a week of early voting, and eliminated same-day registration;43 a strict voter-identification law in Texas;44 and a documentary proof-of-citizenship requirement for voter registration in Kansas.45 Some other cases remain ongoing, such as a challenge to an Arizona law prohibiting the collection of absentee ballots (which was upheld by a Ninth Circuit panel, but is pending before the en banc court).46 The bottom line is that, despite mixed results, litigation challenging recent voter-suppression efforts has seen at least some success in recent years.

However, litigation to bring about affirmative reforms such as EDR has not achieved the same level of success. That is not for lack of trying. Plaintiffs (including some represented by the ACLU) in several states have brought federal or state constitutional claims to abolish voter-registration deadlines, and thereby require their states to adopt EDR.

The federal claims have been litigated under the Anderson-Burdick test for challenges alleging that a state election law violates the fundamental right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment. That test provides that

[a] court considering a challenge to a state election law must weigh “the character and magnitude of the asserted injury to the rights protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments that the plaintiff seeks to vindicate” against “the precise interests put forward by the State as justifications for the burden imposed by its rule,” taking into consideration “the extent to which those interests make it necessary to burden the plaintiff’s rights.”47

This is, in essence, a simple balancing test.

Under this test, challenges to a state’s requirement to register to vote in advance of Election Day have followed a two-pronged argument. First, advance registration is burdensome, preventing tens of thousands (or, depending on the size of the state, even hundreds of thousands) of voters from exercising the fundamental right to vote. That is, while requiring voters to register several weeks in advance of an election may not sound like much of a burden, it functions as a significant burden in practice. As noted above,the broad consensus among political scientists is that, in any given election, advance registration prevents millions of eligible Americans from casting a ballot—a but-for cause of their not voting.48 From a social-science perspective, the evidence regarding a suppressive effect on turnout is stronger for voter-registration deadlines than it is for many other barriers to voting that have been stuck down as unlawful impositions on the right to vote.

Second, in light of current technology—including statewide electronic voter lists and online registration systems that can verify voter eligibility in real time—the state has no substantial interest in maintaining decades-old advance registration deadlines, which are nothing more than arbitrary historical artifacts. Perhaps in an earlier era, when voter-registration forms were paper-based and processed by hand, a state needed a blackout period of two to four weeks to finalize the voter rolls before Election Day. But the situation is far different today. The Help America Vote Act of 2002 required all states to adopt computerized statewide voter-registration lists.49 Thirty-seven states plus the District of Columbia now offer online voter registration, with most states operating fully paperless systems that validate information submitted by registration applicants by using other information already on file with the state.50 Thus, whatever administrative justifications may have existed when most states’ voter-registration deadlines were adopted decades ago no longer have force today. Maintaining an arbitrary deadline due to inertia ought not justify the disenfranchisement of tens of thousands of voters.

Federal litigation pressing such claims, however, has not been successful thus far, with federal district courts in Connecticut51 and Florida52 sustaining those states’ voter-registration deadlines against constitutional challenges. In both cases, the courts held that registration deadlines are reasonable election regulations that impose only minimal burdens on voters. The Florida district court rejected the plaintiffs’ claims out of hand, summarily dismissing “any suggestion that the registration deadline practically burdens the ability of Floridians to register to vote.”53

But the Connecticut case was more thorough. There, the district court noted that Connecticut’s voter-registration cutoff of only seven days before Election Day is the “shortest-in-the-nation pre-election-day registration requirement;” characterized the burden of registration before Election Day “tak[ing] about one minute of a citizen’s time;” and pointed to the fact that “approximately 75% of the voting-age population of the State” is registered as evidence that registering prior to Election Day is not a significant burden on voters.54 While the plaintiffs in the Connecticut litigation attempted to quantify the impact that Connecticut’s voter-registration deadline had on suppressing turnout, the district court largely discounted their expert testimony as suffering from a “number of flaws,” such that, in the court’s view, the impact of EDR in the state would be “modest”—”closer to one percent than five percent,”55 or about 25,000 voters in a presidential election.56 In light of these findings, the court went on to hold that it was “irrelevant” that the state lacked evidence about the scale of its asserted rationale (preventing voter fraud), because the “modest” burden of voter registration was justified by the goal of “preventing” a potential future (though currently nonexistent) problem of voter fraud.57

Since those cases were decided, there have been more recent federal cases in which plaintiffs (represented by the ACLU58 and others) successfully litigated the issue of same-day registration—but these cases have come solely in the context of challenging the repeal of same-day registration during early voting—with permanent relief in North Carolina59 and a preliminary injunction ruling in Ohio that was ultimately stayed.60 In both cases, courts found that the abolition of same-day registration (during early voting) would be unjustifiably burdensome for at least some voters. For example, in reference to low-income and homeless voters who lack access to transportation, the Ohio district court observed that “the ability to register and vote on the same day ‘can make the difference between being able to exercise the fundamental right to vote and not being able to do so.’”61

But the Ohio and North Carolina cases are arguably inapplicable to situations where a state has never adopted same-day registration in the first place, because there may be different reliance interests in states where voters have grown accustomed to being able to register and vote at the same time—a point we emphasized in briefing in both cases.62 In any event, though federal litigation has been successful (to some degree) at preventing the elimination of same-day registration, it has not been an effective vehicle for establishing same-day registration where it did not previously exist.

State court litigation has not fared better thus far—although some remains ongoing. While state constitutions often contain express guarantees of a right to vote that may go beyond federal constitutional protections,63 ACLU litigation64 to affirmatively establish EDR did not succeed in state courts in New Jersey65 and Massachusetts,66 while litigation challenging New York’s 25-day voter-registration deadline remains ongoing.67

In Massachusetts, we tried to adjust our litigation strategy in light of the preceding federal cases in several ways. First, we picked a state with stronger legal protections for voting rights than currently exist under federal law, and a better factual context than Connecticut. Massachusetts’ constitution has an expressly guaranteed right to vote, which we argued provides stricter limits on laws regulating the franchise than does the U.S. Constitution68 Factually, Massachusetts’ twenty-day registration deadline is almost two weeks longer than Connecticut’s seven-day cutoff, and is longer than the respective deadlines of twenty-four states and the District of Columbia.69

Second, we presented a more robust factual record on the burden of the registration cutoff. This included testimony from several individual voters who were unable to satisfy the state’s registration deadline in the 2016 election.70 It also included substantial expert testimony as to the deadline’s effect, which led the state’s own expert to concede that, in a typical midterm election in Massachusetts, approximately 50,0000 to 100,000 voters would make use of same-day registration (which the trial court regarded as an underestimate)—but are effectively disenfranchised by the current voter-registration deadline.71

Third, we also pointed to the fact that the state had essentially no justification for its particular registration cutoff, because Massachusetts’ early voting period begins only five days after its registration deadline.72 In other words, the state already processes voter-registration applications in just five days and had no reason for a registration deadline almost three weeks before Election Day.73The twenty-day deadline was just an artifact of a different time period, rendered arbitrary by more recent innovations.

And yet, even here, we did not succeed. Despite a resounding trial court decision finding that Massachusetts’ registration deadline deprives thousands of eligible voters of their right to vote under the state constitution, and that there is “no real reason, grounded in data, facts or expert opinion, why election officials need to close registration almost 3 weeks before the election to do their job,”74 the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court reversed. The decision largely ignored the evidence at trial as to the actual effect of the registration deadline. It expressed “concern that, given the passage of time . . . the twenty-day blackout period may need to be reconsidered” as no longer necessary,75 yet ultimately upheld it based on the anodyne observation that “at least for the time being, an impartial lawmaker could logically believe that the voter registration deadline imposed twenty days prior to election day still serves legitimate public purposes that transcend the harm to those who may not vote.”76

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court was able to arrive at that result by ignoring the record of disenfranchisement caused by the state's voter registration deadline; a court seriously considering that record would have a difficult time issuing such a ruling. But no state court of last resort has done so yet, which begs a question: Why have some courts been willing to look carefully at the record of disenfranchisement caused by strict voter ID laws, ultimately striking them down, while no court has yet done so (without being reversed) with respect to voter-registration deadlines—even though it is likely that registration deadlines prevent more people from voting than strict ID requirements? Of course, this is a bit of an apples-to-oranges comparison, as the same courts did not hear all of these cases. So perhaps it has just been luck of the draw.

Or maybe there is a difference between the character of the burden imposed by a voter ID law and an advance registration deadline. For certain groups of voters (for example, the poor, the elderly, those who lack access to transportation), the burden imposed by a voter ID law may simply be altogether impossible to satisfy. On the other hand, it is in theory possible to comply with a registration deadline given sufficient advance notice and ample registration opportunities (which states are presumed, rightly or wrongly, to have). From that perspective, registration deadlines only prevent people from voting who are insufficiently diligent. That is, regardless of how many voters these different barriers actually affect, perhaps courts have viewed them as categorically different from each other in a meaningful way.

While that analytic difference may be the basis for the divergence in how courts have ruled, it is unclear why this distinction should matter. Even under the relatively forgiving Anderson-Burdick balancing test, courts assessing the constitutionality of a voting restriction are supposed to consider the actual evidence of its effect in the record.77

Because state court litigation is ongoing over New York’s registration deadline and may yet be filed in other states, it is far too soon to say that litigation on this issue is futile. A sample size of two state court decisions is hardly a firm basis on which to make sweeping generalizations. But it may be the case that courts’ treatment of registration deadlines thus far speaks to the limits of litigation as a means to accomplish affirmative legal reforms, at least in the voting-rights space. That is, while some courts have been receptive to claims that newly-erected barriers to the franchise violate constitutional or statutory guarantees around the right to vote, courts have been reluctant to find violations where plaintiffs challenge existing practices—even where older practices may be outmoded and/or have a significant effect on voter participation.

This has not always been the case. Historically, courts were willing to strike down longstanding voting practices that once were commonplace, but now, thanks to judicial intervention, seem almost unfathomable—for example, poll taxes of $1.50 in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections,78 and redistricting plans with malapportioned districts containing vastly different population sizes in Reynolds v. Sims.79 Those landmark cases, however, arose in an earlier and very different era. In more recent years, there have been many examples of successful defensive voting-rights litigation—blocking new barriers to voting, or preventing rollbacks of existing reforms—but it is difficult to think of a major affirmative reform in the area of registration or voting access that has been accomplished through litigation over the last four decades.80 The obvious inference is that, today, courts have something of a status-quo bias, which would be unsurprising. Courts are generally conservative institutions that—while sometimes willing to defend civil rights from new incursions—are generally more hesitant about being pressed into service for the project of affirmative reform.

Given our experience thus far attempting to litigate voter-registration deadlines, efforts to expand EDR should focus primarily on legislative reform. Bringing EDR to all fifty states is undoubtedly a significant political challenge, but there is some momentum. Although EDR has existed for decades, the number of states that have adopted it has more than doubled in the last decade (from nine states in 2009 to twenty states plus the District of Columbia today).81 As noted, EDR has been adopted in states across the political spectrum, including among recent adopters (such as Utah in 2018). In fact, solidly “red” states may be the most promising targets for state-level EDR reforms in the short term, where legislators may have less fear about the partisan consequences of expanding the electorate.

There is, however, probably a ceiling on how far state-by-state efforts can take us. While many states have recently adopted EDR, they tend to be states where one party has a relatively solid lock on the levers of power, such as Washington and Utah in 201882—places where voting reforms are unlikely to alter the electorate so significantly as to threaten existing partisan control. The states with divided partisan control of state government that have adopted EDR in recent years have circumvented state legislatures via ballot initiatives, such as Michigan and Maryland in 2018.83 It may be the case that legislatures in such “battleground” states will remain resistant to significant reforms that could expand the electorate in ways that could tilt the partisan balance of those states.

H.R. 1, however, could bypass these state-by-state fights and bring EDR to all fifty states in one swoop. Of course, H.R. 1’s prospects are themselves uncertain—which is perhaps unsurprising given the wide range of issues that it addresses.84 A standalone federal bill on EDR, however, is another option. While I am no expert on short-term political realities in Congress, it is possible that a standalone EDR bill could stand a better chance at passage, given that a nearly half of the states have already adopted EDR themselves. Either way, a federal EDR mandate would represent perhaps the most significant expansion of access to the franchise in decades.

Conclusion

The recent burst of voter-suppression measures marks an inflection point in the five decades of progress for voting rights that began with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. These attacks on voting rights represent a backlash to the culmination of that period of expansion: the election of the nation’s first African-American President85 by what was at that point the most diverse electorate in our nation’s history.86 Litigation to win these fights is critical to ensuring that our democracy remains representative in a meaningful sense.

Ultimately, however, preventing the enactment or implementation of measures that make it harder to register to vote or cast a ballot is a defensive exercise. If high levels of civic engagement and voter participation make for more representative and responsive government, then fighting voter suppression—while necessary—is insufficient. Affirmative registration and voting-reform efforts are critical to facilitate participation, particularly among historically disenfranchised and low-participation groups. For now, at least, such reforms are more likely to be adopted through legislation than through litigation.

Dale E. Ho is the Director of the ACLU Voting Rights Project. The views expressed in this Essay should not be attributed to the ACLU. The author wishes to thank Emily Rong Zhang for research assistance, and Paul Gronke, whose expert report in the North Carolina same-day registration litigation pointed me towards much of the social science literature concerning EDR and turnout cited in footnote 11 of this Essay.

Drew DeSilver, U.S. Trails Most Developed Countries in Voter Turnout, Pew Res. Ctr. (May 21, 2018), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/21/u-s-voter-turnout-trails-most -developed-countries [https://perma.cc/3DW7-3C47].

Same Day Voter Registration, Nat’l Conf. St. Legislatures (June 28, 2019), http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/same-day-registration.aspx [https://perma.cc/G68J-S6UY].

See, e.g., Michael J. Hanmer, Discount Voting: Voter Registration Reforms and Their Effects 104 (2009) (finding an approximately 4% increase in voter turnout resulting from Election Day registration); Leighley & Nagler, supra note 6, at 115-16 (up to 6.6%); Steven J. Rosenstone & John Mark Hansen, Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America 208 (1993) (5.6%); Craig Leonard Brians & Bernard Grofman, Election Day Registration’s Effect on U.S. Voter Turnout, 82 Soc. Sci. Q. 170, 170 (2001) (“EDR[] is predicted to produce about a 7-percentage-point turnout boost in the average state.”); Barry C. Burden et al., Election Laws, Mobilization, and Turnout: The Unanticipated Consequences of Election Reform, 58 Am J. Pol. Sci. 95, 96 (2014) (noting “a consistent line of research” that EDR increases turnout by three to seven percentage points in presidential elections); Mark J. Fenster, The Impact of Allowing Day of Registration Voting on Turnout in U.S. Elections from 1960 to 1992, 22 Am. Pol. Q. 74, 80 (1994) (4.7%); Mary Fitzgerald, Greater Convenience but Not Greater Turnout: The Impact of Alternative Voting Methods on Electoral Participation in the United States, 33 Am. Pol. Res. 842, 856 (2005) (“greater than 3 percentage points in midterm congressional elections”); Benjamin Highton & Raymond E. Wolfinger, Estimating the Effects of the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, 20 Pol. Behav. 79, 87 (1998) (8.7% in the 1992 presidential election); Robert A. Jackson, Voter Mobilization in the 1986 Midterm Election, 55 J. Pol. 1081, 1087 n.4 (1993); Stephen Knack, Election-Day Registration: The Second Wave, 29 Am. Pol. Res. 65, 70 (2001) (“about 3 to 6 percentage points”); Michael McDonald, Portable Voter Registration, 30 Pol. Behav. 491, 495 (2008) (“7.1% points”); Roger Larocca & John S. Klemanski, U.S. State Election Reform and Turnout in Presidential Elections, 11 St. Pol. & Pol’y Q. 76, 96 (2011) (noting that “both polling-place and centralized Election Day registration are generally associated with a consistently higher likelihood of voting”); Jonathan Nagler, The Effect of Registration Laws and Education on U.S. Voter Turnout, 85 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 1393, 1396 (1991) (up to 6.2%); Jacob R. Neiheisel & Barry C. Burden, The Impact of Election Day Registration on Voter Turnout and Election Outcomes, 40 Am. Pol. Res. 636, 645 (2012) (“approximately three percentage points”); Staci L. Rhine, An Analysis of the Impact of Registration Factors on Turnout in 1992, 18 Pol. Behav. 171, 179 (1996) (finding that “turnout would increase approximately 14 percentage points”); Caroline Tolbert et al., Election Day Registration, Competition, and Voter Turnout, in Democracy in the States: Experiments in Election Reform 83 (Bruce E. Cain et al. eds., 2008) (up to 4.5%).

See U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-16-630, Issues Related to Registering Voters and Administering Elections 35 (2016), https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/678131.pdf [https://perma.cc/BJ39-Y42M].

See, e.g., Brians & Grofman, supra note 11 (finding significant effects among voters of lower income and education and larger impacts among African Americans as compared to whites); Charlotte Hill & Jacob Grumbach, Opinion, An Exciting Simple Solution to Youth Turnout, for the Primaries and Beyond, N.Y. Times (June 26, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019 /06/26/opinion/graphics-an-excitingly-simple-solution-to-youth-turnout-for-the-primaries-and-beyond.html [https://perma.cc/XTJ6-TH9S] (estimating a turnout increase of “as much as 10 percentage points” among 18- to 24-year-olds).

See Behind the 2018 U.S. Midterm Election Turnout, U.S. Census Bureau (Apr. 23, 2019), https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/04/behind-2018-united-states-midterm -election-turnout.html [https://perma.cc/JFS8-4RDH].

As measured by percentage of the voter-eligible population and as calculated by Michael McDonald of the U.S. Elections Project. See America Goes to the Polls 2018: Voter Turnout and Election Policy in the 50 States, Nonprofit VOTE & U.S. Elections Project 7-8 (2019), https://www.nonprofitvote.org/documents/2019/03/america-goes-polls-2018.pdf [https:// perma.cc/E4J9-Q9VG]. The top ten states were: Minnesota (EDR), Colorado (EDR), Montana (EDR), Wisconsin (EDR), Oregon (no EDR), Maine (EDR), Washington (adopted EDR, but had not yet implemented for 2018), North Dakota (EDR), Michigan (adopted EDR via ballot initiative in 2018 and will implement in 2019), and Iowa (EDR). Id.

Millions of voters are purged from rolls annually. See Jonathan Brater et al., Purges: A Growing Threat to the Right to Vote, Brennan Ctr. for Just. 2 (July 20, 2018), https://www .brennancenter.org/publication/purges-growing-threat-right-vote [https://perma.cc/4RZ6 -3A26] (“Between the 2014 and 2016 elections, roughly 16 million names nationwide were removed from voter rolls.”). In 2018, the Supreme Court upheld Ohio’s system of purging voters for inactivity, based on the assumption that the failure to vote in several election cycles is a proxy for identifying people who have moved to another jurisdiction, see Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Inst., 138 S. Ct. 1833 (2018), despite evidence that thousands of such voters remained eligible to vote and had not in fact moved. See Brief for Respondents at 20, Husted, 138 S. Ct. 1833 (No. 16-980), 2017 WL 4161967 (noting that the purge process at issue flagged more than 7,000 voters for removal in the 2016 election).

Of course, EDR is not the only important registration or voting reform contained in H.R. 1. Automatic Voter Registration (AVR) is another significant registration reform in the bill and currently has significant momentum; since 2017, it has been enacted by eighteen states and the District of Columbia. See Automatic Voter Registration, Nat’l Conf. St. Legislatures (Apr. 22, 2019), http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/automatic-voter-registration.aspx [https://perma.cc/GB3M-T2DJ]. Anecdotally, comparing the 2014 and 2018 elections, Oregon, the first state to adopt AVR, had the largest turnout increase between the two midterms. See America Goes to the Polls 2018, supra note 16, at 10. AVR represents an important philosophical shift that would place the onus of voter registration on the state rather than on individuals, aligning U.S. practices with those of most other democracies. See Wendy R. Weiser, Automatic Voter Registration Boosts Political Participation, Brennan Ctr. for Just. (Jan. 26, 2016), https://www.brennancenter.org/blog/automatic-voter-registration-boosts-political-participation [https://perma.cc/E5GR-6939]. Moreover, AVR bears one comparative advantage over EDR: by registering voters well before an election, AVR enables political parties and nonpartisan organizations to mobilize these voters through get-out-the-vote efforts, which some studies suggest improve turnout. See, e.g., Donald P. Green & Alan S. Gerber, Get Out the Vote: How to Increase Voter Turnout (2015). However, empirical analyses of AVR’s effect on turnout are still quite limited, given the newness of AVR. Moreover, for voters who have been wrongfully purged or who have not been registered due to administrative errors, AVR does not provide the same last-resort safety net on Election Day as EDR. And finally, the vast majority of states with AVR use it only for citizens who interact with a state department of motor vehicles (DMV); only a handful even seek to automatically register voters who only interact with other state agencies. See Automatic Voter Registration, supra. Presumably, this is because most states’ electronic systems for public-assistance offices and other agencies are not sufficiently up-to-date. This particular reform, then, may not always necessarily address the equity concerns that should accompany efforts to improve voter access. Indeed, although the National Voter Registration Act is commonly known as the “Motor-Voter Law,” Congress made sure it contained provisions for registration through state agencies that provide public assistance and disability services, due to concerns that limiting registration to DMVs would exclude vulnerable populations. See H.R. Rep. No. 103-66, at 19 (1993) (Conf. Rep.). None of this is meant to minimize the significance or potential of AVR (and these reforms are not mutually exclusive), but simply to explain why, for purposes of this Essay, I focus on EDR instead as potentially the most important reform currently available for improving voter turnout.

See id. at 6-7 (acknowledging “less clarity” in existing research regarding the effect of voter ID laws on turnout); see also Benjamin Highton, Voter Identification Laws and Turnout in the United States, 20 Ann. Rev. Pol. Sci. 149, 149 (2017) (concluding that existing research finds “modest, if any, turnout effects of voter identification laws”). As I have noted elsewhere, voter turnout estimates used for statistical analyses are likely too imprecise to detect the effects, if any, of strict voter ID requirements. See Ho, supra note 4, at 812-15.

Compare Bernard L. Fraga & Michael G. Miller, Who Does Voter ID Keep from Voting? 6 (Dec. 14, 2018) (unpublished working paper), https://www.dropbox.com/s/lz7zvtyxxfe5if8 /FragaMiller_TXID_2018.pdf [https://perma.cc/GC5G-3H99], which finds that approximately 16,000 voters cast ballots in Texas under a court-ordered exception to Texas’s voter ID law, who would otherwise have been disenfranchised absent the exception, with Michael J. Pitts, Photo ID, Provisional Balloting, and Indiana’s 2012 Primary Election, 47 U. Rich. L. Rev. 939, 951 (2013), which finds only 122 provisional ballots cast by voters lacking requisite ID under Indiana’s voter ID law.

See Pitts, supra note 27, at 946 (acknowledging that that there may be voters who lack ID and are deterred from attempting to vote in the first place); id. at 947 n.48 (acknowledging that the Indiana voter ID study excludes those who appear at a polling place but are not offered a provisional ballot, or whose provisional ballot is not accepted).

See Ho, supra note 4, at 811-15 (arguing that turnout is therefore not the best way to assess the significance of voter-suppression measures); see also Pamela S. Karlan, Turnout, Tenuousness, and Getting Results in Section 2 Vote Denial Claims, 77 Ohio St. L.J. 763, 771-72 (2016); Robert S. Erikson & Lorraine Minnite, Modeling Problems in the Voter Identification-Voter Turnout Debate, 8 Election L.J. 85, 87 (2009).

See, e.g., Fish v. Kobach, 309 F. Supp. 3d 1048, 1074-79 (D. Kan. 2018) (final judgment) (describing plaintiffs unable to comply with Kansas’s documentary proof-of-citizenship requirement for voter registration); Frank v. Walker, 17 F. Supp. 3d 837, 859 (E.D. Wis. 2014) (describing voters unable to comply or who faced significant difficulty in complying with Wisconsin’s voter ID requirement), rev’d, 768 F.3d 744 (7th Cir. 2014).

Richard L. Hasen, The 2016 U.S. Voting Wars: From Bad to Worse, 26 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 629, 630 (2018) (“In the period since 2000, the amount of election-related litigation has more than doubled compared to the period before 2000, from an average of 94 cases per year in the period just before 2000 to an average of 258 cases per year in the post-2000 period.”).

Id. at 631 (“Even compared to the 2012 presidential election cycle, litigation is up significantly; it was twenty-three percent higher in the 2015-16 presidential election season than in the 2011-12 presidential election season, and at the highest level since at least 2000 (and likely ever).” (footnote omitted)); see Ho, supra note 4; Karlan, supra note 29, at 771-72; Daniel P. Tokaji, Applying Section 2 to the New Vote Denial, 50 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 439, 481-82 (2015).

See Ho, supra note 4, at 799-801; Dale E. Ho, Voting Rights Litigation after Shelby County: Mechanics and Standards in Section 2 Vote Denial Claims, 17 N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y 675, 676-77 (2014). As I note in both articles cited here, however, the nationwide surge in voter-suppression practices began before the Shelby County decision, in the run-up to 2012 presidential election. The triggering event, then, might have been the 2008 election of the nation’s first Black president, Barack Obama, by what was, at the time, the most diverse national electorate in U.S. history. See Defending Democracy: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America 7-14 (2012), NAACP Legal Def. & Educ. Fund, https://www.naacpldf.org/wp-content /uploads/Defending%20Democracy%2012-16-11__Political_Participation__.pdf [https://perma.cc/RYQ9-YGE8].

Frank v. Walker, 768 F.3d 744 (7th Cir. 2014). Although the Seventh Circuit upheld Wisconsin’s voter ID law on facial challenge, litigation remains ongoing with respect to plaintiffs’ as-applied challenges to the law. See Frank v. Walker, 819 F.3d 384 (7th Cir. 2016) (remanding for consideration of as-applied claims).

Online Voter Registration, Nat’l Conf. St. Legislatures (Oct. 10, 2018), http://www.ncsl.org /research/elections-and-campaigns/electronic-or-online-voter-registration.aspx [https://perma.cc/N9DR-AUAM].

See League of Women Voters of N.C. v. North Carolina, 769 F.3d 224, 246 (4th Cir. 2014) (granting preliminary injunction based on finding that “same-day registration . . . [was] enacted to increase voter participation, that African American voters disproportionately used [it], and that House Bill 589 restricted [it] and thus disproportionately impacts African American voters”), cert. denied, 135 S. Ct. 1735 (2015). The law was ultimately found unconstitutional on discriminatory-intent grounds. N.C. State Conference of the NAACP v. McCrory, 831 F.3d 204, 215 (4th Cir. 2016), cert. denied sub nom. North Carolina v. N.C. State Conference of the NAACP, 137 S. Ct. 1399 (2017).

See Ohio State Conference of the NAACP v. Husted, 768 F.3d 524, 539, 561 (6th Cir. 2014) (upholding a preliminary injunction blocking the elimination of the “Golden Week”—a one-week period of early voting and same-day registration in Ohio). After the Supreme Court granted a ninety-day stay of the decision, see Husted v. Ohio State Conference of the NAACP, 573 U.S. 988 (2014), the preliminary injunction, which extended only through the 2014 general election, was vacated by the Sixth Circuit as moot. See Ohio State Conference of the NAACP v. Husted, No. 14-3877, 2014 WL 10384647 (6th Cir. Oct. 1, 2014). The case ultimately settled, restoring weekend and evening early voting hours, but leaving in place Ohio’s abolition of the Golden Week. See Settlement Agreement Among Plaintiffs & Defendant Sec’y of State John Husted, Ohio State Conference of the NAACP v. Husted, Case No. 14–cv–404, Doc. No. 111-1 (S.D. Ohio Apr. 17, 2015).

See, e.g., Joint Reply Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants at *5, N.C. State Conference of the NAACP, 831 F.3d at 204 (Nos. 16-1468, 16-1469, 16-1474), 2016 WL 3355830 (arguing that “eliminating provisions on which voters have come to rely creates a burden not present in states that never had those mechanisms”); Appellees’ Brief at *4-7, Ohio State Conference of the NAACP, 768 F.3d at 524 (No. 14-3877), 2014 WL 4792744 (noting the number of voters, including poor and homeless voters, who “rely” on same-day registration); id. at *23-27 (noting that previous cases did not “involve contexts where, as here, the state sought to eliminate long-standing voting opportunities”); id. at *45 n.14 (arguing that there is a “critical difference” between “when [voting] opportunities are eliminated” and when they have never been offered at all).

See Joshua A. Douglas, The Right to Vote Under State Constitutions, 67 Vand. L. Rev. 89, 143 (2014) (“A renewed, independent focus on state constitutions and their explicit grant of the right to vote is textually faithful to both the U.S. and state constitutions and will restore the importance of the most foundational right in our democracy.”).

An intermediate state appellate court rejected a state constitutional challenge to New Jersey’s voter-registration deadline. See Rutgers Univ. Student Assembly v. Middlesex Cty. Bd. of Elections, 141 A.3d 335, 343 (N.J. Super. App. Div. 2016) (holding under state law that New Jersey’s twenty-one-day deadline “imposes no more than a minimal burden upon plaintiffs’ right to vote”).

There, the trial court recently denied the state’s motion to dismiss. See Decision and Order, League of Women Voters of N.Y. v. N.Y. Bd. of Elections, No. 160342/2018 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Oct. 4, 2019). I note that this case does not seek to establish EDR, but simply to shorten New York’s existing voter-registration deadline.

Voter Registration Deadlines, Nat’l Conf. St. Legislatures (Aug. 5, 2019), https:// http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/voter-registration-deadlines [https:// perma.cc/GX87-3VKG]. North Dakota does not require registration; nineteen states (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, Utah, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, Wyoming) and the District of Columbia permit EDR; two states have deadlines between one and fourteen days before the election (Nebraska and North Carolina); and two states have registration deadlines between fifteen and nineteen days before the election (Alabama and South Dakota). Id.

Indeed, I note that, while the ACLU “strongly supports the provisions of H.R. 1 that would strengthen federal protections for the right to vote,” the ACLU ultimately opposed H.R. 1 due to First Amendment concerns with some of its campaign finance provisions. See ACLU Letter Opposing H.R. 1 (For the People Act of 2019), Am. C.L. Union (Mar. 6, 2019), https:// http://www.aclu.org/aclu-letter-opposing-hr-1-people-act-2019 [https://perma.cc/9RWB-VN7S].

See Mark Hugo Lopez & Paul Taylor, Dissecting the 2008 Electorate: Most Diverse in U.S. History, Pew Res. Ctr. (Apr. 30, 2009), https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites /5/reports/108.pdf [https://perma.cc/57V3-Y3P3].