Playing Nicely: How Judges Can Improve Dodd-Frank and Foster Interagency Collaboration

abstract. Devised in the aftermath of the most severe financial crisis since the Great Depression, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) was enacted to reduce risk, increase transparency, and promote market integrity. Since Dodd-Frank was signed into law in 2010, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) have promulgated numerous rules to carry out these statutory mandates. This Note analyzes inconsistencies in the two Commissions’ swaps regulations and argues that those inconsistencies have forced regulators and market participants to bear substantial costs and, more importantly, have thwarted the congressional goals underlying Dodd-Frank. To this day, neither the SEC nor the CFTC has offered an adequate justification for its decision not to harmonize swaps rules.

In this Note, I argue that the Commissions’ failure to account for these costs constitutes an illegal exercise of authority. The crux of my argument is that the Commissions cannot perform meaningful cost-benefit analysis or fulfill the Administrative Procedure Act’s (APA) reason-giving requirements without considering the incremental costs generated by regulatory inconsistencies. I conclude that when the SEC and CFTC fail to justify the costs of regulatory divergences, both the APA and the cost-benefit requirements in the agencies’ authorizing statutes can—and should—be read to require the Commissions to adjust their rules to account for the costs of inconsistent and duplicative swaps regulations.

author. Yale Law School, J.D. expected 2017. I am overwhelmingly grateful for the help I have received from friends, mentors, and family in writing this Note. I greatly appreciate the comments and insight I received from the speakers and participants in Professor William Eskridge’s Statutory Interpretation Seminar in Spring 2016. I would also like to thank Joseph Falvey, Hilary Ledwell, Rebecca Lee, Aaron Levine, Megan McGlynn, Urja Mittal, Anna Mohan, and Cobus van der Ven for fantastic feedback at numerous stages of the project, and all the editors of the Yale Law Journal for their meticulous editing. I am especially indebted to Professors Amy Chua, William Eskridge, Jerry Mashaw, John Morley, and Gabriel Rosenberg for their guidance and inspiration. Finally, I thank my family and Sophia Veltfort.

Introduction

In early April 2012, just two years after Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank),1 a sense of déjà vu paralyzed financial markets. On April 6, the press reported that J.P. Morgan had suffered significant losses because of trades executed in its London office.2 A week later, CEO Jamie Dimon dismissed these reports as a mere “tempest in a teapot.”3 But the loss turned out to be more than that. One month later, J.P. Morgan disclosed that its losses had ballooned from $415 million to $2 billion.4 By the end of the year, transactions executed by a single J.P. Morgan trader named Bruno Iksill—more commonly known as the “London Whale”—led to a $6.2 billion trading loss.5 In other words, barely two years after the most consequential financial regulatory reform in decades, a major financial institution took risky bets that once again roiled global credit markets. And—even more troubling—it did so right under the nose of its regulators.

A year-long Senate investigation followed. The investigation concluded that the American financial system would be less vulnerable to systemic shocks if federal regulators required more comprehensive financial reporting,6 used more accurate risk models,7 and finalized rules prohibiting banks from using money held in federally insured deposit accounts to make speculative investments that did not benefit their customers.8

The usefulness of the Senate Report, however, was undermined by the fact that existing regulations rendered many of its recommendations superfluous. Dodd-Frank already required that data on swaps,9 the financial instruments traded by the London Whale,10 be reported on publicly accessible exchanges.11 The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), one of the agencies charged with monitoring swaps and detecting destabilizing financial positions, had finalized swap-reporting rules in March 2012. Those rules went into effect at the beginning of 2013.12

Nor did the Report mention that banks had already begun to report swap data in anticipation of the CFTC’s rules. In the aftermath of the London Whale incident, Michael Bodson, the chief executive of a company that collected swap data, acknowledged that data on the London Whale’s trades had been reported to swap data repositories.13 The problem was that although CFTC rules specify what data must be reported, the rules do not explain how data repositories should report information.14 According to Bodson, regulators failed to detect the London Whale’s position not because the data was unavailable, but because formatting incompatibilities rendered it unusable.15

Significantly, however, Title VII of Dodd-Frank does not grant regulatory authority over swaps solely to the CFTC, but divides oversight between the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the CFTC.16 Title VII grants the SEC the authority to regulate security-based swaps and the CFTC the authority to regulate all other swaps.17 In accordance with its own statutory mandate, the SEC issued its final rule on the reporting and public dissemination of security-based swap information over three years after the CFTC’s rules went into effect.18 Dodd-Frank split oversight between the two agencies in order to avoid alienating members of Congress who served on the agricultural committees,19 who had made it clear that they would vote against any bill that removed the CFTC from their jurisdiction.20

In abandoning regulatory consolidation, Title VII permitted the SEC and CFTC to create a fragmented reporting regime that has raised the costs of complying with Dodd-Frank while making it more difficult for regulators to supervise the swaps market. There is no question that the SEC and CFTC are each statutorily required to issue swaps regulations.21 Nonetheless, the effectiveness of the SEC’s and CFTC’s rules depends in large part on whether their rules are compatible.22 This Note analyzes recent D.C. Circuit cost-benefit cases in order to argue that the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and the cost-benefit mandates in the agencies’ organic statutes, both individually and in tandem, require that the SEC and CFTC either justify the costs of regulatory inconsistencies or harmonize their regulations. Thus, in addition to offering a possible solution to the SEC’s and CFTC’s unwillingness to promulgate consistent swaps rules, this Note offers a new, albeit limited, defense of cost-benefit analysis. Recently, a number of academics have criticized “judicially reviewed, quantified”23 cost-benefit requirements as an exercise in futility and a judicially sanctioned attempt to quantify the unquantifiable.24 By forcing agencies to harmonize their rules when they cannot offer a reasonable justification for an inconsistency, I show that cost-benefit requirements can discipline agency action in cases involving overlapping agency jurisdiction.

This Note proceeds in three parts. Part I provides a brief overview of Dodd-Frank and examines existing rules governing swap reporting and swap execution facilities (SEFs). This Part shows that the SEC’s and CFTC’s failure to collaborate has created unnecessary costs, made the American financial system less transparent, and introduced unjustified risk into the market. Part II analyzes the cost-benefit and APA requirements that govern SEC and CFTC rulemakings. I argue that the two agencies are legally required to consider how their swaps regulations interact. Although practitioners and scholars have argued that it is desirable for the two agencies to collaborate,25 almost no one has suggested that collaboration is legally required.26 Part III describes my model of judicial review and considers how the SEC and CFTC might respond if this model were put into practice.27 In addition, Part III examines cases in which other agencies have collaborated voluntarily and argues that the form of judicial oversight I endorse would grant the SEC and CFTC broad discretion to choose the most effective method of harmonizing their rules.

My argument applies not only to swaps, but also to other areas in which the APA and cost-benefit requirements could reduce some of the inefficiencies that occur when Congress requires agencies to administer regulatory initiatives jointly. New regulations are not written on a blank slate; they interact with a complicated and dynamic administrative apparatus. Agencies must therefore consider how their rules will interact and whether these interactions undermine the effectiveness of new rules.

i. the effects of inconsistent swaps regulation

Congress enacted Dodd-Frank in the wake of the 2008 recession to reduce risk in U.S. financial markets. In this part, I explain how Title VII of Dodd-Frank seeks to accomplish this goal. I then identify two elements of Dodd-Frank—swap-reporting rules and SEF rules—in which inconsistencies between the SEC’s rules and the CFTC’s rules impose unnecessary costs without providing any identifiable benefit. I further argue that these conflicting rules ultimately compromise Dodd-Frank’s goal of controlling systemic risk.

A. The 2008 Recession and Title VII of Dodd-Frank

The Great Recession of 2008 is widely considered to be the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.28 Despite aggressive and unprecedented efforts by the Department of Treasury and the Federal Reserve, unemployment rose to ten percent—a thirty-year high29—and housing prices fell thirty-three percent,30 costing Americans $16.4 trillion in household wealth.31

Although the causes of the financial crisis continue to be debated,32 it is clear that swaps—in particular, credit default swaps—played a critical role in allowing individual companies to accrue risk sufficient to cause the global economy to collapse.33 Credit default swaps are akin to insurance on bonds. When a bank buys a bond, say from General Electric (GE), the bank expects to receive a steady stream of payments from GE over the life of the bond. However, if GE were to go bankrupt, the bank would stop receiving those payments. To hedge against that possibility, the bank might buy a credit default swap from another company. The credit default swap would require the bank to pay a premium at regular intervals. In exchange, the company that sold the credit default swap would agree to pay a large sum if the entity that borrowed funds from the bank cannot afford to pay the interest on its bond. As long as GE can afford to pay its interest payments, the bank loses its premium payments. But if GE were to go bankrupt, then the bank would receive money from the party that sold the bank the credit default swap. In this way, credit default swaps allow companies to insure against the possibility that a counterparty will not be able to honor its obligations.

At the end of 2007, the credit default swaps market was worth $60 trillion.34 Companies used credit default swaps to protect against nearly every possible contingency, from changes in bonds and stocks to fluctuations in interest rates and housing prices.35 The portfolio of one credit default swap seller, AIG, covered bonds worth more than $440 billion.36 AIG did not have sufficient funds to honor all of its obligations. As a result, Moody’s Investor Service, a credit rating agency, downgraded AIG’s credit rating. Because of the terms of the credit default swap contracts, AIG had to post more collateral—which it did not have—to guarantee its ability to pay its credit default swap obligations. AIG’s inability to make good on its credit default swap obligations thus meant that banks immediately lost their insurance on $440 billion worth of bonds.37 Overnight, the banks were worth billions less.38 This, in turn, meant that banks had less money to lend, which meant that other banks had to borrow at higher costs.39 Some banks no longer had enough money available to cover their costs. Others could not afford to borrow under these new terms. Weak banks faced collapse, which threatened to cause the money supply to contract further. Absent a government intervention, the inability of AIG, a single firm, to make good on its credit default swap obligations exposed the entire global economy to substantial risk.40 A similar story played out with Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, and Merrill Lynch, among others, though in the case of Lehman Brothers, the government allowed the company to fail.41

One of the reasons that individual companies such as AIG were able to assume such risky positions was because before Dodd-Frank, swaps were generally traded “over-the-counter” (OTC).42 In other words, deals were negotiated and executed privately between two parties.43 As a result, there was no central repository of information and no way for regulators or counterparties to determine if an individual counterparty would be able to honor its swap obligations. Banks were unable to discover how badly other banks were affected, and so at the first sign of trouble, these financial institutions stopped lending to each other out of fear that their counterparties were overexposed.44 As the CFTC has noted, OTC trading made the swaps market “less transparent than exchange-traded futures and securities markets.”45 The CFTC went on to describe “[t]his lack of transparency [as] a major contributor to the 2008 financial crisis because regulators and market participants lacked visibility to identify and assess the implications of swaps market exposures and counterparty relationships.”46 The lack of swaps exchanges and reliable reporting systems thus enabled single companies, such as AIG, to take significant and sizable positions that left the global financial system at risk.47

Congress passed Dodd-Frank in 2010 in direct response to the recession.48 The statute’s goal was to prevent another crisis of such scale and to “promote the financial stability of the United States by improving accountability and transparency in the financial system.”49 To that end, Title VII of Dodd-Frank established a new framework for the regulation of the swaps market by authorizing the SEC and CFTC to regulate OTC derivatives, including swaps.50 Under Title VII, the SEC and CFTC must establish margin requirements,51 rules for clearing and trade execution,52 and real-time reporting.53 These rules ensure that the vast majority of transactions are reported to regulators, that swaps are traded on a market rather than through bilateral transactions, and that one firm’s inability to honor its obligations does not bankrupt the firm’s counterparties.

Key to these reforms was creating pre- and post-trade transparency in swap deals. Reporting requirements attempt to provide post-trade transparency by ensuring that upon the completion of every swap, regulators and market participants can receive volume and pricing information.54 Reporting requirements seek to ensure that regulators and market participants can look at the swaps market and identify systemic risk early enough to prevent a financial crisis.55 Title VII sought to create pre-trade transparency by establishing SEFs, or trading platforms roughly analogous to stock exchanges that allow swap participants to trade swaps on a competitive exchange.56 The existence of competitive trading platforms makes information about swaps available to the market by making swap bids (offers to buy a swap if certain terms are met) and offers (offers to sell a swap if certain terms are met) available to interested parties. Thus, Dodd-Frank seeks to bring swaps out of the opaque world of bilateral backroom dealing by forcing parties in a swap deal to use transparent trading systems and platforms.57

As a political compromise,58 Title VII divided oversight of swaps between the SEC and the CFTC. It granted the SEC the authority to regulate security-based swaps and the CFTC the authority to regulate all other swaps.59 Yet the Act did not define the terms “swap” and “security-based swap.” Instead, Dodd-Frank instructed the SEC and CFTC to issue a joint rulemaking defining those terms,60 which the agencies did on August 13, 2012.61 By that time, however, the CFTC had already issued a number of swap-related regulations.62 As a result, market participants had to begin setting up compliance programs without knowing which financial instruments would eventually be subject to CFTC requirements.

As a general rule, the CFTC oversees the majority of swaps, including swaps based on interest or other monetary rates, and the SEC regulates swaps based on a single security, loan, or narrow-based security index63—that is, a security index that has nine or fewer underlying securities.64 Thus, if a party wants to purchase a swap based on eight securities, it would be subject to SEC rules, and if the party traded a swap based on ten securities, it would be subject to CFTC rules.65

To be sure, Dodd-Frank attempted to reduce the costs of dual agency oversight of swaps by directing the SEC and CFTC to “adopt rules to ensure that such transactions and accounts are subject to comparable requirements to the extent practicable.”66 Yet as the rest of this Section shows, the SEC and CFTC have been reluctant to follow this mandate, and the incompatibility of their swaps rules has dramatically increased the costs of derivatives regulations and thwarted regulatory attempts—and Congress’s original goals—to make the swaps market safer and more transparent.

B. Inconsistencies in Rules Governing Swap Reporting

In December 2011, the CFTC approved its final rule on swap data recordkeeping and reporting requirements.67 The CFTC then issued additional final rules governing swap reporting in March 2012, and swap dealers began reporting data for index-based and interest-rate swaps shortly thereafter.68 Over three years later, in February 2015, the SEC issued its own final rule on the reporting and public dissemination of security-based swap information.69 Shortly thereafter, in August 2015, the CFTC issued a notice of proposed rulemaking to revise parts of its swaps rules.70 The Commission finalized these revisions ten months later.71 While similar in many respects, the two rules reflect important differences in terms of what must be reported and who must report the information.

Swap transactions generally consist of the “initial transaction” between the two parties and two “clearing transactions” between the clearing agency and the two parties. In most cases, the CFTC and the SEC require that all three be reported, but their requirements differ in certain cases. Under CFTC rules, if the initial transaction is accepted for clearing prior to being reported, the derivatives-clearing organization (rather than one of the parties to the swap) is required to report the initial transaction.72 Under SEC rules, one of the parties to the initial transaction, rather than the clearing agency, is required to report the initial security-based swap.73

This inconsistency imposes substantial costs on the regulated community. To comply with the CFTC’s rules, financial institutions had to build reporting infrastructures in 2012 without knowing whether that infrastructure would be compatible with the SEC’s rules for security-based swaps. Then, three years later, these institutions had to build new reporting infrastructures or update their existing infrastructures in order to allow them to input separate reporting requirements.74

For swaps not traded on a market, both the SEC and CFTC rules reflect an understanding that more sophisticated parties will be better able to understand reporting requirements, build infrastructure, and bear the cost of reporting. For those swaps, the CFTC’s reporting rules place the reporting onus first on any swap-dealer counterparty, then on any major swap-participant counterparty and then, only if neither of those are involved in a swap, on an entity that is not a swap dealer or major swap participant.75 The SEC’s rule generally follows the same reporting order with one crucial difference—if only one party to the swap is defined as a U.S. person (i.e., incorporated in the United States), that person is responsible for reporting.76

As Annette Nazareth and Gabriel Rosenberg have pointed out, what emerges is a bifurcated reporting regime with puzzling results.77 Consider two variants of a standard swap deal. First, imagine that an American corporation enters into an index credit default swap with a London-based swap dealer. Because the transaction involves an index credit default swap, it is subject to CFTC rules.78 The swap dealer is responsible for the immediate reporting of the transaction, and the American corporation is responsible for updating the initial report for the duration of the swap.79 Now imagine that the American company and the London-based swap dealer enter into a credit default swap on a single asset instead of an index. In this case, the transaction would be governed by SEC rules, so an American corporation would be responsible for reporting the transaction.80 Data repositories are repeat players in the swaps market and are therefore likely to understand their reporting obligations. Individual corporations, by contrast, may trade swaps infrequently. It is therefore likely that they will lack reporting infrastructure and may not even know that they have a duty to report. Forcing individual companies—especially small companies that lack experience in financial markets—to report swap information already imposes a fairly substantial burden on swap participants. This inefficiency is aggravated by the fact that companies must comply with two different regimes. Every American company that wants to trade swaps must therefore understand not only that they are occasionally responsible for reporting the initial swap transaction, but also that this requirement differs depending on which set of rules governs a swap. The agencies could have avoided this inefficiency by agreeing on a single, consistent reporting framework. Indeed, neither agency has provided a sufficient explanation for its decision to enact regulations that diverge from the other regulator’s rules in costly but seemingly insignificant ways.81

Additional costs arise from distinct requirements about what data must be reported. While the CFTC’s rules include detailed tables of required data elements for various types of swaps,82 the SEC initially set out only the basic elements of reportable information in its final rule on swap reporting, leaving the data repositories that store SEC-traded swaps responsible for sorting out the details for each product type.83 Nor does the SEC ask for underlying valuation data.84 In contrast, the CFTC requires that the derivatives-clearing organization report daily valuation data. 85 And, if the reporting counterparty for the initial transaction is a swap dealer or major swap participant, then the counterparty is also responsible for reporting daily valuation data.86 Both the SEC and CFTC reporting regimes use coded identifiers (IDs) to identify a person, product, or transaction.87 However, the SEC requires more granular information on the parties executing the transaction, including IDs related to the broker, trader, trading desk, counterparty, product, and transaction.88 By contrast, the CFTC requires only that swap participants report the legal-entity identifiers of the parties to a swap, as well as the unique product and unique swap identifiers.89

The SEC and CFTC also disagree about the definition of block trades, which are large trades with the potential to move the market.90 The CFTC, but not the SEC, has set minimum amounts for block trades.91 In contrast, the SEC’s proposed rule would delegate to swap data repositories the authority to establish policies and procedures for calculating which trades constitute block trades.92 The SEC defended this decision for preserving flexibility.93 However, it did not mention the fact that inconsistent rules about block trades will force market participants, data repositories, and clearinghouses to set up two different programs to report and execute the largest and most significant block trades.

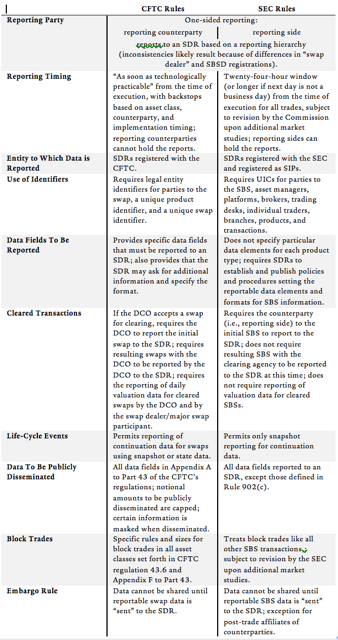

The table below shows important differences between SEC and CFTC requirements for reporting swap information to swap data repositories:94

table 1.

reporting requirements for swap data repositories (SDRs)

Note: DCO: derivatives clearing organization, SBS: security-based

swap, SBSD: security-based swap dealer, SDR: swap data repository, SIP:

securities information processor, UIC: unique identification code

Market participants repeatedly expressed concerns about the costs of complying with inconsistent swaps rules during both agencies’ rulemaking processes. For example, in a comment letter on the SEC’s proposed rule on data repositories, the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC), one of the four swap-reporting organizations currently registered with the CFTC,95 urged the SEC and the CFTC to “harmonize the regimes that oversee [swap data repositories].”96 DTCC emphasized that “harmonization is a more important priority than the exact nature of the consistent standard, as SDRs can adjust to meet a single standard but not multiple, inconsistent standards.”97 Gibson Dunn echoed DTCC’s complaint, arguing that “[w]here regulatory requirements diverge, market participants must develop practical and sound reporting policies and procedures for each respective reporting regime.”98

Others have expressed concern that regulatory inconsistencies will prevent market participants from using swap data. The Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), an interest group that represents the securities industry,99 asked that market participants be able to “review [swap data-repository] reported trade information for trades executed on behalf of clients, or otherwise process such information in an automated fashion”; that “client trade information [be] made available to asset managers in an easily accessible, easy to read format”; and that “consistent specifications and reporting fields [be] utilized to harmonize reporting requirements across jurisdictions and to ensure the interoperability of such information.”100 SIFMA worried that regulatory inconsistencies would make it impossible for buyers to analyze the market and monitor the exposure of their counterparties. In the case of swaps not traded on exchanges, inconsistencies between SEC and CFTC rules would therefore prevent buyers from assessing the competitiveness of the products they purchase. Though SIFMA discussed the operational difficulties of inconsistent regulations, its concerns point to a potentially more pernicious cost than those associated with mere compliance. Not only will buyers’ inability to analyze the swaps market increase the cost of engaging in transactions, but it will also prevent swap counterparties, who are the first line of defense against systemically risky positions, from detecting those build-ups.

Data incompatibility also threatens to undermine regulators’ ability to detect destabilizing swap build-ups. As even regulators themselves have admitted, inconsistent swaps rules make it more difficult to supervise the swaps market. The astronomical losses caused by the London Whale, discussed above, show that this concern is not merely hypothetical. In a speech about the challenges that the CFTC faced in analyzing data promulgated solely under its rules, CFTC Commissioner Scott O’Malia drew attention to the London Whale incident and offered a frank assessment of the obstacles posed by inconsistent swap reporting. Noting that “[t]he goal of data reporting is to provide the Commission with the ability to look into the market and identify large swap positions that could have a destabilizing effect on our markets,” the Commissioner reported that “the Commission’s progress in understanding and utilizing the data in its current form and with its current technology is not going well.”101 Commissioner O’Malia pointed out that formatting incompatibilities rendered the reams of swap information submitted to the CFTC effectively useless. According to Commissioner O’Malia, because the CFTC did not specify in what format reporting parties should submit data, the Commission had been unable to track and analyze developments in the swaps market.102 Commissioner O’Malia also noted that members of the CFTC’s staff had acknowledged that they “currently cannot find the London Whale in the current data file,”103 and he went on to testify that destabilizing swap positions will only be visible to the SEC and the CFTC if the Commissions “work to harmonize rules sets as far as possible, particularly in clearing, trading and reporting.”104

Recall that a primary objective of Dodd-Frank was to increase transparency in the swaps market.105 In furtherance of this goal, reporting requirements were intended to help agencies identify swap positions that could endanger the global economy.106The trading losses incurred by the London Whale, however, illustrate how reporting incompatibilities have already prevented regulators from identifying when parties have taken systemically important and risky swaps positions.But even if the CFTC fixes its own internal reporting problems, differences between its reporting requirements and those issued by the SEC will present regulators with additional challenges. In addition to imposing perplexing and unjustified costs on market participants, these inconsistencies will continue to impede detection of systemically important swap positions.

C. Inconsistencies in Rules Governing SEFs

Like swap-reporting rules, inconsistent regulations governing SEFs raise the costs of complying with Dodd-Frank while reducing transparency in the market. An SEF is a regulated “trading system or platform in which multiple participants have the ability to execute or trade swaps by accepting bids and offers made by multiple participants in the facility.”107 For swaps traded on an exchange, Dodd-Frank charges the SEC with regulating security-based swaps and the CFTC with regulating most other swaps.108 As soon as the CFTC finalized its SEF rules in 2013, market participants began building SEFs to conform with the agency’s rules.109 In contrast, the SEC issued its proposed rules in 2011, but it has yet to finalize them.110

The critical distinction between the CFTC’s SEF rules and the SEC’s proposed rules is whether the agency or the SEF should determine if a certain type of transaction must be traded on an SEF.111 Both agencies agree that swaps that are “made available for trading” must be traded on an SEF and that other swaps can continue trading through bilateral transactions rather than on an exchange.112 However, the SEC has proposed that the agency should determine which products are made available for trading,113 while under existing CFTC rules, the SEFs themselves determine which products are made available for trading, subject to CFTC approval.114

Buyers have expressed concern that allowing SEFs to determine when swaps are available for trading will incentivize manipulative behavior. For example, the Managed Funds Association, a group that represents the interests of the hedge fund industry,115 asked the CFTC “to make the ‘available for trading’ determination” itself.116 The Managed Funds Association worries that the discretion given to SEFs “will create considerable uncertainty among marketparticipants.”117 It is concerned that individual SEFs will identify a product that is not traded on other SEFs and quickly establish “an overnight monopoly” over that product.118 This would reduce competition and favor larger, wealthier SEFs. It would also force buyers who would like access to all types of swap products to connect to all SEFs. Otherwise, buyers risk being crowded out of a market because they are not connected to a SEF that trades a desirable product. The CFTC SEF regime might therefore incentivize SEFs to determine opportunistically that a product has been made available for trading in order to establish a monopoly for that product. Because this opportunism is not available in the SEC’s regime, SEFs operating under the CFTC’s rules are less likely to choose to trade security-based swaps.

SEFs therefore need to decide whether to develop systems flexible enough to meet both the CFTC’s and SEC’s requirements or whether to focus exclusively on one asset class. If CFTC-specific and SEC-specific SEFs develop, market participants will need to become members of and build technological connections to both. Twenty-five SEFs currently operate under the CFTC rules,119 which apply to seventy-three percent of credit default swaps and to sixty-nine percent of all interest rate swaps.120 Because the CFTC market is so large, SEFs may lack the incentive to create a separate infrastructure for the SEC’s SEF regime. And if SEFs do choose to specialize in one regulator’s rules and create separate SEFs for SEC or CFTC rules, then swap traders would have to pay for additional SEF connections if they want to access all products. Thus, unless the SEC changes the trade determination in its final rules, the agencies’ failure to harmonize their SEF rules will lead to the same outcome as in the reporting context: inefficiencies without benefits.

D. Failure to Consider the Costs of Inconsistent Swaps Regulations

While the SEC and CFTC are certainly aware of the benefits of harmonizing their swaps regulations,121 the agencies have offered only cursory analyses of the costs of inconsistent swaps regulations. The SEC’s analysis of SEFs is a powerful example. The Commission’s cost-benefit analysis fills just two columns in its forty-six-page notice in the Federal Register and does not once mention the CFTC’s regulations.122 The CFTC proposal is no different. As MarketAxess, a company interested in trading both SEC- and CFTC-governed swaps, pointed out, the CFTC’s proposal “does not analyze the cost of organizing and operating a SEF,” nor does it “consider the burden of its proposal or review[] the regulatory costs of possible alternative regulatory approaches to its proposal.”123

This failure to consider harmonizing swaps regulations is not unique.124 The Commissions rarely mention how existing swaps rules might affect their cost-benefit analyses, and even when they do, their analyses either assert that they have harmonized where possible, or simply raise the possibility that inconsistent regulations are a problem. The agencies do not analyze inconsistencies or otherwise consider harmonizing their rules. For example, in footnote 356 of the CFTC’s proposed rule on margin requirements for uncleared swaps, the agency acknowledges that regulatory arbitrage—the possibility that market participants will modify their products in order to avoid the CFTC’s margin requirements—might render its proposed regulation less effective.125 The CFTC further notes that if its margin requirements differ substantially from those of the other regulators, “operational inefficiencies” may prevent traders from “utilizing congruent operational and compliance infrastructure.”126 In plain English, the agency is acknowledging that companies may have to set up separate compliance regimes for each agency’s rules even though those rules regulate the same type of financial product. But after admitting that the actions of other financial regulators will affect whether its own regulations will require companies to set up more than one compliance program, the CFTC dismisses the dangers of regulatory arbitrage by asserting that it has “consulted and coordinated with” the appropriate regulators “in order to harmonize [their] respective margin rules to the greatest extent possible.”127 However, the CFTC then admits that “[t]he baseline against which the costs and benefits associated with this rule will be compared is the status quo, [that is], the uncleared swaps markets as they exist today.”128 Therefore, although the CFTC concedes that rules promulgated by other agencies will determine whether its own rules are effective, the agency analyzes the costs and benefits of its rules against a backdrop of the unregulated, pre-Dodd-Frank swaps market.

Similarly, in response to comments requesting that the CFTC harmonize pricing and reporting requirements with the SEC’s rules, the CFTC acknowledged the “concerns expressed,” but countered that “industry solutions...will mitigate” those costs.129 Yet nowhere in the CFTC’s eight-page cost-benefit analysis does the CFTC explain why the benefits of its rule justify the costs to market participants of implementing two different reporting systems. Nor did the CFTC justify its decision to force market participants to devise creative compliance programs capable of accommodating two reporting regimes when the alternative—consistent regulations—would have allowed market participants to develop a single reporting program.130 The CFTC’s cost-benefit analysis in its rules for block trades follow a similar pattern. The CFTC acknowledged that several commenters urged the Commission to “harmoniz[e] with the SEC’s approach” to designating block trades,131 and a number of other commenters asked the two agencies to “coordinate...in setting minimum block levels.”132 Yet after acknowledging these comments, the CFTC’s cost-benefit analysis did not walk through the benefits of coordinating with the SEC or the costs of inconsistencies.133

Like the CFTC’s rules, the SEC’s final reporting rules failed to justify inconsistencies with the CFTC’s rules. Although the SEC admitted that it “has taken into consideration comments received supporting harmonization of the CFTC’s rules for swap data repositories with the SDR Rules,” the Commission responded to these comments by saying that it “believes that the final SDR Rules are largely consistent with the rules adopted by the CFTC.”134 In another rulemaking, the SEC again conceded that “it would be beneficial to harmonize, to the extent practicable, the information required to be reported under Regulation SBSR and under the CFTC’s swap-reporting rules.”135 Nevertheless, the SEC countered that “the flexibility” of its reporting rule “will facilitate harmonization of reporting protocols and elements between the SEC and CFTC reporting regime.”136 Notably, the SEC issued this cost-benefit analysis over three years after the London Whale incident. Nevertheless, the SEC did not mention that granting data repositories flexibility had prevented regulators from detecting a systemically significant swap build-up. Nor did it explain how it would detect potentially destabilizing swap positions given the likelihood that reporting inconsistencies would render swap data unusable.137

Granted, the SEC and the CFTC have publicly acknowledged that regulatory inconsistencies render their regulations more expensive,138 and they have independently recognized that they are required to consider the potential costs and benefits whenever they regulate. For instance, the SEC has released a “standard template”139 to explain how it would measure costs and benefits when promulgating rules under Dodd-Frank.140 The CFTC has also recently indicated that it plans to take its cost-benefit mandate more seriously, entering into a memorandum of understanding with the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) to obtain “technical assistance...during the implementation of [Dodd-Frank], particularly with respect to the consideration of the costs and benefits of proposed and final rules.”141 The SEC and CFTC have also distributed internal guidance explaining how they should comply with cost-benefit requirements. In March 2012, the SEC cited “[r]ecentcourt decisions, reports of the U.S. Government Accountability Office...and the SEC’s Office of Inspector General... and Congressional inquiries” that had “raised questions about...the Commission’s economic analysis in its rulemaking.”142The SEC guidance noted that, “as SEC chairmen ha[d] informed Congress since at least the early 1980s—and as rulemaking releases since that time reflect—the [SEC] considers potential costs and benefits as a matter of good regulatory practice whenever it adopts rules.”143The SEC guidance directed rulemaking staff to work with economists to analyze which costs and benefits a rule might create, to quantify those that could be quantified, and to explain why others could not feasibly be quantified.144

And yet these attempts to improve cost-benefit analysis have not persuaded the agencies to coordinate their swaps rules, nor have they persuaded politicians and economists that the agencies have begun to take their cost-benefit obligations seriously. For example, the CFTC’s approach to considering costs and benefits under the standard template has come under heavy criticism, not just from market participants complaining about particular rulemakings, but also from economists,145 members of Congress,146 and CFTC commissioners. CFTC Commissioner Jill Sommers admitted, “The proposals we have issued thus far contain cursory, boilerplate cost-benefit analysis sections in which we have not attempted to quantify the costs because we are not required to do so under the Commodity Exchange Act.... [W]e should most certainly attempt to determine whether the costs outweigh the benefits.”147 The Inspector General of the CFTC has even issued a report finding that the CFTC had adopted a “one size fits all” approach and had not given sufficient regard to “addressing idiosyncratic cost and benefit issues that were shaping each rule, and [were] often addressed in the preamble.”148

In sum, while the costs that duplicative regulations impose on industry participants are serious, they are not the most significant problem with the current regime. As the London Whale incident shows, the inconsistent regulations promulgated by the SEC and CFTC have made important data about the market exposure of industry participants more opaque and less accessible to regulators. The inconsistent regulations promulgated under Dodd-Frank have thus undermined the law’s goal of reducing systemic risk. Although the SEC and CFTC have occasionally acknowledged the costs of these inconsistencies, to date, they have not justified these costs in their rulemakings.

ii. Regulatory Harmonization Through Cost-Benefit Mandates and the APA

Fortunately, cost-benefit mandates and the APA, both individually and in tandem, require the SEC and CFTC to consider the effects that their rules will have on market fragmentation and liquidity. The SEC and CFTC are statutorily required to justify their rules and respond to proposals that they harmonize their swaps regulations.149 If the SEC and CFTC cannot provide a reasoned response to comments requesting that they harmonize swaps rules, then they must adjust their rules until they can offer a justification. Granted, neither cost-benefit mandates nor the APA have yet been used to encourage agencies to coordinate.150 But, as this Part shows, judicial review of interagency coordination follows logically from the current doctrine. This Part argues that judicial review of the agencies’ unwillingness to coordinate would not only force the Commissions to offer public justifications for their refusal to harmonize swaps regulations, but that the exercise of offering reasons for regulatory divergences would itself induce the agencies to work together.

A. APA Requirements

Under the APA, an agency’s failure to consider alternative regulations should be considered an illegal exercise of authority.151 Section 553 of the APA requires agencies to describe proposed rules in a general notice of proposed rulemaking,152 to give third parties the opportunity to comment on proposed rules,153 and to respond to relevant comments in a “concise general statement of their basis and purpose.”154

These requirements were famously articulated in Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Ass’n v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance.155 In State Farm, the Supreme Court held that the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) acted arbitrarily and capriciously in revoking Standard 208, which required automakers to include passive restraints in all new cars.156 While the agency had explained why car companies should not be required to install one kind of passive restraint—ignition interlocks—it gave no consideration to an alternative restraint mechanism that it had already proposed: mandating the use of airbags. According to the majority, because the agency “entirely failed to consider” this “important aspect of the problem,” its action was considered arbitrary and capricious under the APA.157

Indeed, a long line of administrative law cases has established that section 553 requires agencies to respond to comments when implementing new rules.158 Failure to do so renders agency action arbitrary and capricious, and therefore invalid. As the D.C. Circuit explained in Home Box Office, Inc. v. FCC, an agency “has an obligation to make its views known to the public in a concrete and focused form so as to make criticism or formulation of alternatives possible.”159

The Supreme Court explained how courts should evaluate agency justifications for major administrative actions in Citizens To Preserve Overton Park, Inc. v. Volpe. According to the majority, courts should “consider whether the decision was based on a consideration of the relevant factors and whether there has been a clear error of judgment.”160 The court went on to clarify that, “[a]lthough this inquiry into the facts is to be searching and careful, the ultimate standard of review is a narrow one.”161 In other words, the courts police agency justifications but are prohibited from “substitut[ing their] judgment for that of the agency.”162 A court that finds an APA violation can remand the rule back to the agency for reconsideration.163

The SEC’s and CFTC’s inconsistent regulation of swaps would fail this standard of APA review. As discussed in Part I, regulatory inconsistencies create burdensome costs for market participants and render the rules less effective at reducing systemic risk. Moreover, the industry has already laid the groundwork for APA review through its comments, which repeatedly urge the agencies to harmonize their swaps regulations.164 If the rules were challenged under the APA, a court should find that the rules were not “based on a consideration of the relevant factors.”165

Critically, as with any other rulemaking challenge under the APA, a court should remand the rule back to the respective agencies, who would then have the opportunity to resubmit the rules based on additional fact finding.166 Thus, the reviewing court would not order the agencies to collaborate or otherwise oversee agency efforts to harmonize their rules. Instead, it would merely ensure that the SEC and CFTC have provided reasons for promulgating inconsistent swaps rules. If the reasons passed the APA’s standard of arbitrary and capricious review, the rules would withstand judicial scrutiny. If not, the SEC and CFTC would have to go back to the drawing board or harmonize their regulations. In other words, the court would be constrained to remanding—not invalidating—rules that are insufficiently justified.

B. Cost-Benefit Mandates

Like the APA, cost-benefit requirements in the CFTC’s and SEC’s organic statutes require the agencies to consider alternative regulatory approaches and to justify their proposed rules against these alternatives. There are three principle differences between cost-benefit analysis and the APA. First, cost-benefit analysis—but not the APA—explicitly requires agencies to consider the economic consequences of a rule as an additional factor when justifying the rule. Cost-benefit mandates therefore force agencies to go through not only the procedural requirement of considering relevant facts, but also the substantive requirement of showing that the benefits of an action outweigh the costs. Although courts still defer to agencies’ substantive judgments about the net benefits of a rule, cost-benefit mandates open up room for judges to ensure that agencies give reasoned justifications of the societal usefulness of new rules.167 Second, cost-benefit mandates ask agencies to consider less costly alternatives even if no one raised those alternatives during notice and comment.168 Third, an agency must perform cost-benefit analysis only when a specific substantive statute requires that the agency conduct such an analysis. It is therefore not required of every administrative agency.

The authorizing statutes of both the SEC169 and the CFTC170 require the agencies to engage in cost-benefit analysis when promulgating new rules. The Commissions must therefore show that a proposed rule outweighs possible alternatives, regardless of whether a third party has suggested the alternative in a comment. In interpreting the agencies’ cost-benefit mandates, courts have emphasized that the agencies must justify their regulations not in relation to a hypothetical state in which other agencies do not exist, but in relation to the existing regulatory landscape. Thus, the SEC’s and CFTC’s failure to respond to comments requesting regulatory harmonization constitutes an arbitrary exercise of each agency’s regulatory authority in a way that independently violates each agency’s statutory cost-benefit mandate.

The D.C. Circuit has elaborated the SEC’s cost-benefit requirements in a series of cases beginning in the early 2000s. Chamber of Commerce v. SEC171 was the first case to interpret section 80a of the Investment Company Act, which instructs the Commission to consider the effect of a new rule on efficiency.172 In Chamber of Commerce, the D.C. Circuit remanded an SEC rule requiring mutual funds’ boards of directors to have independent chairmen and to have at least seventy-five percent of their directors be “independent” of management.173 The D.C. Circuit held that the rule failed to comply with the SEC’s cost-benefit requirement for two reasons. First, the SEC did not quantify the costs of requiring seventy-five percent independent directors.174 The court held that the SEC should have attempted to quantify this cost even though the Commission did not know whether boards would respond to the rule by increasing the number of directors on boards or by replacing incumbent directors.175 Second, the SEC failed to justify the requirement that these boards have an independent chair.176 The SEC recognized that newly independent chairs might hire staff, but it declined to quantify those costs because it stated that it could not predict how many chairs would hire staff, or how many staff members each chair would hire. Again, the court found this excuse unavailing.177

According to the majority, these deficiencies constituted not only a violation of the SEC’s specific cost-benefit mandate, but also a violation of the APA. The court held that the SEC violated the APA by failing to consider a proposal raised in comment letters that suggested that mutual funds be required to disclose publicly whether they had independent chairs.178 The court noted that the SEC justified its decision not to consider this alternative on the ground that the SEC had no obligation to consider every alternative raised, that it did consider other alternatives, and that Congress in the Investment Company Act179 itself had not relied on disclosure alone to police conflicts of interest in funds.180 To this, the court responded, “[T]hatthe Congress required more than disclosure with respect to some matters governed by the [Investment Company Act] does not mean it deemed disclosure insufficient with respect to all such matters.”181

Furthermore, because the SEC did not consider whether an alternative regulatory regime would be equally effective and less costly, the Commission “fail[ed] adequately to consider the costs that mutual funds would incur in order to comply with the conditions.”182Chamber of Commerce therefore interpreted the Securities Exchange Act’s requirement that the SEC “consider” a rule’s effects on “efficiency”183 to imply a robust cost-benefit mandate. Pursuant to this mandate, the SEC must consider not only whether the net benefits are economically justified compared to the status quo, but also whether the costs are justified when compared to less expensive alternatives.

SinceChamber of Commerce, the D.C. Circuit has invalidated a number of financial regulatory actions for failing to satisfy the APA and the agencies’ cost-benefit mandates.184 Concerns about the adequacy of financial regulators’ cost-benefit analyses intensified after the D.C. Circuit’s opinion in Business Roundtable v. SEC,185 which overturned the SEC’s “proxy access” rule. The proxy access rule made it easier for shareholders to nominate outside candidates to become directors of publicly traded companies.186 Calling the SEC’s statutory mandate to perform cost-benefit analysis a “unique obligation,” the court held that the agency’s “failure to ‘apprise itself—and hence the public and the Congress—of the economic consequences of a proposed regulation’ ma[de] promulgation of the rule arbitrary and capricious and not in accordance with law.”187 As in Chamber of Commerce, the SEC’s failure to consider certain costs triggered violations of both the APA and of the Commission’s cost-benefit mandate. In language that is relevant to the regulation of swaps, the court observed that “the Commission inconsistently and opportunistically framed the costs and benefits of the rule; failed adequately to quantify the certain costs or to explain why those costs could not be quantified; neglected to support its predictive judgments; contradicted itself; and failed to respond to substantial problems raised by commenters.”188

Though not discussed as frequently as Chamber of Commerce or Business Roundtable, the case most germane to the financial regulators’ swaps regulations is a 2010 opinion decided by the D.C. Circuit.The case, American Equity Investment Life Insurance Co. v. SEC,189 explicitly held that the SEC could not determine whether an annuities regulation would be effective without first considering how the rule would interact with existing state annuitieslaws.190 Specifically, the question in American Equity was whether an SEC regulation was warranted given the fact that state law already provided a “baseline level of price transparency and information disclosure.”191 According to the court, the SEC’s failure to show that its rule would improve the existing state law regime constituted a violation of its cost-benefit mandate. The court further held that the SEC’s failure triggered an APA violation as well: “The SEC’s failure to analyze the efficiency of the existing state law regime renders arbitrary and capricious the SEC’s judgment that applying federal securities law would increase efficiency.”192 American Equity therefore established that the existing regulatory landscape can be a relevant fact in APA and cost-benefit analysis.

American Equity was unique in the recent line of D.C. Circuit cases overturning SEC rules for inadequate cost-benefit analysis.193 While most of these cost-benefit cases criticize the Commission for insufficiently justifying the costs and benefits of its own proposed rules,194 American Equity criticized the SEC for failing to consider whether another regulatory regime rendered an SEC rule redundant. As the court explained, “The SEC could not accurately assess any potential increase or decrease in competition...because it did not assess the baseline level of price transparency and information disclosure under state law.”195

American Equity is remarkable for at least three reasons. First, it is one of very few cases to acknowledge that in certain situations, the effectiveness of a regulation depends on how that regulation interacts with the regulatory apparatus as a whole.196 Second, it suggests a role for the judiciary—namely, as the regulatory harmonizer of last resort—that a number of scholars have criticized on the ground that judges are ill-equipped to supervise administrative agencies.197 And third, the court viewed this supervisory function as a logical and unremarkable extension of the court’s duty to ensure that agencies offer publicly accessible reasons to justify new rules.

The underlying facts of American Equity ensured that it would not prompt regulatory harmonization. This is because the question in that case was whether the SEC rule was warranted in the first place. The SEC sought to regulate an activity that was already subject to robust disclosure requirements under state law. Appellants sought to show that the SEC rule should be invalidated. Swaps are different. As Part I explained, the SEC and the CFTC oversee different kinds of swaps, and there is no question that the agencies are each statutorily required to issue regulations governing the swaps under their jurisdiction.198 The question is therefore not whether one of the agencies has jurisdiction over swaps, but whether the SEC and CFTC considered how their rules would interact. As the next Part shows, applying the logic of American Equity to the SEC’s and CFTC’s swaps rules would create a strong incentive for the agencies to collaborate and reduce regulatory inconsistencies.

Three years after American Equity, the D.C. Circuit decided Investment Co. Institute v. CFTC,199 which also considered remanding a financial regulation for failure to consider how the rule would interact with another financial regulator’s rule. Investment Co. Institute considered the legality of a CFTC rule requiring certain companies that had previously been exempt from CFTC registration requirements to register with the CFTC. Appellants argued that the rule should be invalidated because the CFTC “ignored existing SEC regulations that could provide the necessary information about investment companies’ activities in derivatives markets” and therefore failed to consider whether “existing regulations made its proposed regulation unnecessary.”200 As in American Equity, the question was whether the agency had given adequate consideration to the existing regulatory apparatus. In this case, however, the court found that the CFTC had complied with the APA and its cost-benefit mandate. The court distinguished the case from Business Roundtable and American Equity on the grounds that the CFTC had consulted with the SEC and “surveyed the existing regulatory landscape and...found that its registration and reporting requirements could fill gaps in current regulations.”201 The court also drew attention to the fact that the CFTC planned to reduce inconsistencies between its rule and the SEC’s rule, explaining that the CFTC had “issued a notice of proposed rulemaking for a harmonization, the entire purpose of which was to synchronize SEC and CFTC regulations, further distinguishing this case [Investment Co. Institute]from American Equity and Business Roundtable.”202 Thus, the CFTC satisfied its cost-benefit requirement because it considered how its rule would interact with SEC rules, and because it planned to make further efforts to harmonize its rules and reduce the costs of regulatory inconsistencies.

Investment Co. Institute considered another question that is relevant for SEC and CFTC swaps regulations. Specifically, the court determined that a regulator must consider how its rule will interact with the existing regulatory apparatus—not how the rule would affect a hypothetical regulatory regime that might develop after another regulator acts at a later date. In Investment Co. Institute, appellants argued that the CFTC could not measure the costs and benefits of the rule because the CFTC had decided to perform a “multi-step rulemaking with some regulations becoming final only after harmonization with SEC regulations.”203 According to appellants, the CFTC’s failure to delay implementation until it had coordinated with the SEC introduced an unjustifiable level of uncertainty and allowed the CFTC to “count[] benefits that may not materialize... while ignoring costs that may result from that rule.”204 Appellants therefore urged the CFTC to adopt its rules only after harmonizing its rule with the SEC’s rule. The D.C. Circuit disagreed. According to the court, the CFTC had “no obligation to consider hypothetical costs that may never arise.”205 The implication of the court’s opinion is that the court will not force agencies to modify the timing and substance of a new rule based on the likelihood that future rules will determine the efficacy of the currently proposed rule. Instead, courts should ensure that agencies have considered the existing regulatory landscape.

Investment Co. Institute therefore seems to favor the first mover when agencies regulate in shared administrative spaces. In the case of swaps, the CFTC may benefit from having enacted a number of swap-reporting rules before the SEC. While the CFTC need not consider costs and benefits that may or may not materialize, the SEC, by virtue of enacting swaps rules after the CFTC, must consider the regulatory apparatus that has emerged as a result of the CFTC’s swaps rules. As a result, Investment Co. Institute suggests that the SEC must either make its rules consistent with the CFTC’s rules or explain why it has chosen to take a different path. The CFTC has since amended its reporting rules, but since the CFTC issued these amendments after the SEC promulgated its reporting rules,206 the CFTC would have to consider how these modifications affect the SEC’s rules.

As this Part has shown, both the APA and the specific statutory cost-benefit mandates of the SEC and CFTC make clear that these agencies are legally required to consider the broader regulatory environment into which a proposed rule will enter. Regardless of whether an agency must engage in cost-benefit analysis, the agency’s failure to consider alternative regulations proposed during notice and comment triggers an APA violation that justifies judicial remand of the rule. If an agency is also governed by a cost-benefit mandate, reviewing courts can engage in a more searching review of the agency’s justification of the social utility of the rule, regardless of whether a specific regulatory alternative has been raised in comments.

iii. How Judicial Review Can Foster Interagency Collaboration

The previous Section explained that the APA and the SEC’s and CFTC’s cost-benefit mandates require the agencies to consider how a new rule will interact with the existing regulatory apparatus. This Part explains how judicial enforcement of that standard would incentivize interagency collaboration. Critically, courts would not order agencies to act in a certain way, or even to collaborate. Instead, they would simply enforce well-established principles of administrative law that were articulated in iconic cases like State Farm and Overton Park.

This Part also clarifies how judicial review might work in tandem with executive and legislative attempts to facilitate agency collaboration. I argue that judicial review need not come at the expense of legislative or executive attempts to induce regulatory harmonization. Rather, judicial review would impose a baseline reason-giving requirement that would apply regardless of whether the executive or the legislature also sought to require collaboration. This Section shows that, in certain cases, judicial review may even prove more desirable than executive or legislative intervention. While executive or legislative interventions involve potentially burdensome intrusions from outside parties, judicial review would empower agencies by granting them broad discretion to decide how best to mediate the costs of inconsistencies.

iii. How Judicial Review Can Foster Interagency Collaboration

As Part II discussed, established doctrine permits courts to determine whether an agency has given adequate consideration to the ways a rule will interact with the existing regulatory apparatus. The analysis in this Part shows that applying that principle to swaps would encourage the SEC and CFTC to reduce inconsistencies and collaborate when necessary.

The basic point is that by forcing the SEC and CFTC to engage in a more searching analysis of the costs of inconsistent swaps rules, courts would create a powerful incentive for the agencies to harmonize their regulations. Frederick Schauer has shown that the act of giving reasons can discipline the institutions that give those reasons. According to Schauer, “when institutional designers have grounds for believing that decisions will systematically be the product of bias, self-interest, insufficient reflection, or simply excess haste, requiring decisionmakers to give reasons may counteract some of these tendencies.”207 On this view, the act of giving reasons can itself discipline agency action by limiting the scope of available discretion. A cynic may criticize agency decisions for being rash or self-interested, but so long as agencies give publicly accessible reasons, administrative choices cannot be justified solely on self-serving grounds. Schauer further notes that “[a] reason-giving mandate will also drive out illegitimate reasons when they are the only plausible explanation for particular outcomes.”208

One can understand recent cost-benefit cases as seeking to realize this ideal of reasoned administration. The D.C. Circuit’s case law leaves little doubt about the SEC’s and CFTC’s cost-benefit mandates: agencies must consider whether alternative regulations would better achieve a statute’s objectives at a lower cost. The law is emphatic, and there is no reason to think that a proposal asking the agencies to consider how their rules interact is any different from the American Equity requirement that the SEC consider how its rule fits into the state-governed insurance regulatory regime.209

I should note that this case law is far from uncontroversial. Business Roundtable was criticized for imposing an unrealistic burden on regulatory agencies.210 Academic commentary focused on the court’s willingness to force the SEC to do the impossible and provide an accurate quantitative assessment of the rule’s costs.211 Specifically, scholars criticized Judge Ginsburg’s admonition that the SEC’s cost-benefit assessments “had no basis beyond mere speculation” because the agency failed “to estimate and quantify the costs it expected companies to incur....”212

However, one need not adopt Judge Ginsburg’s claim that cost-benefit analysis requires that agencies quantify costs to conclude that the SEC’s and CFTC’s failure to account for each other’s swaps regulations has jeopardized the lawfulness of their rules. In fact, the SEC and CFTC swaps regulations would fail even a relaxed version of Business Roundtable. Part II showed that current law requires agencies to give reasons for costly inconsistencies. To satisfy this requirement, the agencies are obligated to consider the rules’ effects on the current regulatory regime, including their marginal benefits and costs in light of existing regulations. They have failed to do this. Thus, if someone challenged their swaps rules, it is in a court’s legal power to remand the agencies’ swaps rules for reconsideration. If the Commissions cannot give a plausible explanation for an inconsistency, they would have to harmonize their rules. As a result, the act of requiring reasons would itself prompt greater interagency collaboration.

This approach is precisely the standard Judge Ginsburg applied in Business Roundtable. The debate about whether it is appropriate to force agencies to quantify their cost-benefit analyses elides a more general point, which is that the D.C. Circuit struck down the SEC’s proxy rules because the agency had failed to “weigh the rule[s’] costs and benefits,” particularly as they related to the existing regulatory environment. And “[w]ithout th[at] crucial datum, the Commission ha[d] no way of knowing whether” its swaps rules would have a “net benefit.”213

Similarly, in the case of swaps, the SEC and CFTC have failed to account for a “crucial datum,” which is whether their rules will be effective given the regulatory environment created by Dodd-Frank. Without that piece of information, the agencies have no way of knowing if their rules will be effective. Thus, when considering an obviously inconsistent regulation, the SEC and CFTC must provide some justification for the inconsistencies. As discussed in Part I, neither agency has done so in more than a cursory manner, even when confronted with relevant comments from the industry.214 The agencies have neither “explain[ed] why those costs could not be quantified,” nor have they “respond[ed] to substantial problems raised by commenters.”215 In light of State Farm, Business Roundtable, and American Equity, these deficiencies likely violate the APA and the agencies’ statutory cost-benefit mandates. If the agencies continue to be unable to justify unilateral action, they have failed to justify the incremental costs of regulatory inconsistencies and must adopt the proposed alternative and harmonize their rules.

B. Why Judges?

Scholars have generally argued that the executive and the legislative branches are better suited than the judiciary to foster interagency collaboration. Rather than claim that courts do not have the legal authority to force agencies to work together, scholars who adopt this position argue that courts are poorly equipped to induce interagency collaboration. In a recent article describing the difficulties of overlapping swap jurisdiction, Jody Freeman and Jim Rossi argue that Congress and the President are best able to promote interagency collaboration: “Although courts could in theory incentivize interagency coordination with greater deference . . . this shift is neither likely to occur under current doctrine nor warranted . . . the main drivers of coordination should be the legislative and executive branches.”216

Freeman and Rossi thus regard the President and Congress, but not the courts, as possessing powerful tools that can be used to motivate agencies to coordinate. They suggest that the Financial Stability Oversight Committee (FSOC) and, to a lesser extent, OIRA, are best equipped to regulate financial transactions.217 After all, FSOC was established in part to facilitate coordination among the financial regulators,218 and section 112 of Dodd-Frank directs FSOC to monitor and respond to emerging risks to the stability of the U.S. financial system, including risks arising from the swaps market. To this end, Dodd-Frank instructs the Committee to “facilitate information sharing and coordination among the member [and other] agencies”; “identify” potentially perilous “gaps in regulation”; “identify systemically important financial market utilities and payment, clearing, and settlement activities”; recommend that member financial regulators impose certain “standards and safeguards”; and provide a forum for examining changes in markets and regulation and undertaking member dispute resolution.219 Similarly, Executive Order 12,866 provides that significant regulatory actions must be submitted to OIRA for review.220

But Freeman and Rossi overlook the fact that, as a practical matter, executive and legislative efforts to foster interagency collaboration may be poor substitutes for judicial review because such efforts have often produced disappointing results. To date, FSOC has not participated in the swaps rulemaking process.221 In fact, in November 2011, the GAO found that the agency had played only a limited role in providing coordination among its members, which include the SEC and CFTC.222 The report also noted that the coordination tools that FSOC had developed were of “limited usefulness”223 and recommended that FSOC “establish formal coordination policies.”224 Although FSOC broadly agreed with the report’s conclusions,225 a GAO report from September 2012 found that the agency had failed to enact meaningful reforms.226 The report reiterated that FSOC should create “formal collaboration and coordination policies.”227 Despite these continued admonitions, swaps rules remain bifurcated. In September 2014, the GAO reiterated that FSOC has “not adopt[ed] practices to coordinate rulemaking across member agencies....”228

Nor has OIRA fared any better. OIRA has made the CFTC’s cost-benefit analyses longer, but it has not prompted the CFTC to consider how its regulations will interact with the SEC’s rules. This failure may be because the SEC has not worked as closely with OIRA, or it may result from OIRA’s lack of expertise in financial regulation. As Freeman and Rossi point out, “[I]t is not clear that OIRA, as currently constituted, is optimally positioned to sponsor coordination efforts that depend heavily on matters of legal interpretation or on substantive policy considerations beyond economic efficiency.”229 This concern likely applies to OIRA’s expertise with respect to the swaps market. And while the agreement between OIRA and the CFTC has generated more robust cost-benefit analyses, it has not prompted the CFTC to coordinate with the SEC or to consider the effects of inconsistent regulations.

Thus, not only are judges empowered to enforce coordination, but in many cases, they are also the most viable option for increasing agency collaboration. Further, as a doctrinal matter, if neither OIRA nor FSOC succeeds in forcing the agencies to abide by their APA and cost-benefit requirements, then the courts can and should intervene.230

Nor would judicial oversight prevent, or even hinder, other government bodies from helping agencies coordinate their rules. If FSOC or OIRA can succeed in fostering collaboration between the SEC and CFTC, they would thereby succeed in helping the financial regulators satisfy their APA and cost-benefit mandates. But insofar as FSOC and OIRA do not effectively prompt interagency coordination, the judiciary has a role to play in enforcing the reason-giving requirement. To reiterate, judges would not order agencies to adopt a certain rule or regulatory approach—they would simply ensure that agencies provide public justifications for promulgating inconsistent regulations.

Freeman and Rossi also incorrectly assume that the courts should not play a role in resolving disputes between different regulators. In fact, Rossi and Freeman conceive of judicial review as a possible obstacle for agency coordination because insufficient deference might stymie executive efforts to get regulators to work together.231 As I argued in the previous Section, this vision of the judiciary misrepresents judges role in administrative law. Under my proposal, the courts would not tell agencies how to act. Rather, they would use cost-benefit requirements and the APA to enforce the reason-giving requirement in seminal cases like Overton Park232 and State Farm.233 Note that this form of judicial action would empower agencies by allowing them to decide for themselves how to work together. Whereas legislative or executive supervision involves an authority telling agencies how to act, the judicial scrutiny required by cost-benefit analysis and the APA would preserve agencies’ discretion to decide the most effective way to collaborate.

Forcing agencies to consider the effects of regulatory divergences also preserves some of the beneficial effects of overlapping regulatory oversight. Martin Landau has argued that it is often desirable for multiple regulators to oversee the same products.234 Landau defends overlapping regulations because they create a bias toward overprotection. Because multiple regulators often oversee the same financial instrument, duplicative regulations can check bad behavior by establishing backstops that protect against regulatory failures.235 The type of judicial review I envision is fully compatible with justifiable regulatory divergences. In requiring agencies to justify inconsistent regulations, I do not argue that agencies could never enact divergent regulations. But when regulated parties criticize a regulatory divergence, the agency must provide a reasoned justification for the difference. And of course, the judiciary would not be permitted to consolidate multiple agencies or otherwise force formal collaboration. The proposal here is far narrower. It would not compromise the benefits of having multiple perspectives when those benefits are justifiable.

Judicial review of regulatory divergences is also compatible with the views of scholars who defend regulatory fragmentation in certain cases for promoting administrative experimentation. According to some scholars, redundant oversight is desirable because it allows agencies to test different regulatory approaches and encourages agencies to function like laboratories, devising original solutions to difficult administrative challenges.236 For example, Neal Katyal has argued that the overlapping antitrust authority of the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice can be justified on these grounds.237 Similarly, judicial review need not preclude financial regulators from crafting creative solutions to regulating the swaps market. Agencies are required to justify regulatory differences and to defend new approaches with sound logic. Whereas consolidating or eliminating agency functions might deter interagency “competition” and prevent agencies from becoming “laboratories” for creative policy solutions,238 coordinating agency action through judicial review could preserve agency independence while channeling competition in productive ways. It may even prompt agencies to offer public reasons for decisions that use novel approaches.

Perhaps the most challenging critique is that my prescriptive view could contribute to rulemaking “ossification.” Ossification refers to the fact that searching judicial review has occasionally prevented agencies from engaging in meaningful policymaking. Jerry Mashaw and David Harfst, for example, have shown that the judiciary’s willingness to remand rules promulgated by NHTSA pushed the agency away from rulemaking and into “case-by-case adjudication, which requires little, if any, technological sophistication and which has no known effects on vehicle safety.”239 According to Mashaw and Harfst, judicial scrutiny that required NHTSA to justify safety rules with reasons led the agency to abandon rulemaking in favor of a less effective alternative—recalling automobiles after cars were found hazardous.