State Legislative Drafting Manuals and Statutory Interpretation

abstract. Although legislation has become a central feature of our legal system, relatively little is known about how statutes are drafted, particularly at the state level. This Note addresses this gap by surveying drafting manuals used by bill drafters in state legislatures. These manuals describe state legislatures’ bill drafting offices and outline conventions for statutory formatting, grammar, and style. These documents are valuable tools in statutory interpretation as information about drafting offices provides context for analyzing legislative history, and drafting conventions can illuminate statutory meaning. This Note offers normative justifications for using drafting manuals in statutory interpretation as well as principles to guide state courts in considering drafting manuals in their jurisprudence.

author. Yale Law School, J.D. 2016; Dartmouth College, B.A. 2013. I am especially grateful for the direction and advice I received on this project from Professor Nicholas Parrillo. For their careful editing and thoughtful feedback, I thank Hilary Ledwell, Urja Mittal, Jacobus van der Ven, and the editors of the Yale Law Journal.

Introduction

Scholars agree that the main feature of the modern American legal system has become legislation.1 In our “Republic of Statutes,”2 the drafting and enactment of legislation deeply affects our public and private lives in areas ranging from tax and monetary and financial policies to rules that protect consumers from unsafe products.3 When legislatures enact statutes, their members typically intend the words in those statutes to convey particular meanings,4 yet the task of interpreting and applying statutes frequently falls to courts. That is, judges often face the task of determining the meaning of a statute and how it applies in different contexts.5 Judges use a familiar arsenal of interpretive tools for pinpointing the meaning of statutes—text, structure, purpose, legislative intent, and legislative history—and scholars and jurists have developed widely known theories and doctrines about if, when, and how interpreters should consider these features in construing statutes.6 These approaches to statutory interpretation, however, largely consider sources produced during the later stages of the legislative process—namely, after a bill has already been drafted and introduced in the legislature. But how are statutes actually drafted? Relatively little is known about how legislatures draft bills.7 As a result, the legislative drafting process is largely unaccounted for in mainstream statutory interpretation theory.8

However, an emerging literature has begun to examine Congress’s practices and procedures and contemplate the extent to which courts should consider those realities in interpreting statutes.9 Jarrod Shobe has written about the realities and complexities of the legislative process based on his experience working as a professional drafter in the Office of the Legislative Counsel in the House of Representatives.10 Two major empirical studies have looked further at the process by which Congress drafts legislation11: Victoria Nourse and Jane Schacter published a case study of legislative drafting in the Senate Judiciary Committee,12 and Abbe Gluck and Lisa Bressman followed up with a comprehensive survey of 137 congressional staffers on legislative drafting.13

Scholars, however, have not yet accounted for state legislatures and state courts. Apart from a handful of studies conducted a generation ago,14 there is scant literature on the legislative process at the state level—a significant omission since ninety-eight percent of cases in the United States are heard in state courts, and the vast majority of the state court caseload is statutory.15 And yet, while scholars debate whether and how judges should consider the legislative drafting process in statutory interpretation, some state courts have already begun to do so in actual cases.

State courts routinely consider a set of sources that have been little noticed by the academy and largely ignored by the federal judiciary, but that provide key information about the bill-drafting process: state legislative drafting manuals. Every state legislature has a legislative services office comprised of professional, nonpartisan drafters who assist legislators in preparing bills. Thirty-seven states’ offices publish bill drafting manuals that are available to the public and contain a prescribed set of drafting instructions on formatting, grammar, word choice, and style. Although the legislative drafting offices in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives both publish drafting manuals,16 these manuals have played little role in the federal courts’ statutory interpretation jurisprudence.17 By contrast, several state courts have cited drafting manuals to assist in resolving statutory questions. The manuals enable courts to construe statutes in light of the drafters’ shared understandings of the legislation and the intended meanings of particular words and phrases.18 These developments are key to the emerging debate about the role of the legislative drafting process in statutory interpretation theories and doctrines.19

This Note is the first to offer a comprehensive and detailed examination of the bill drafting manuals and to consider how they should be used in statutory interpretation.20 This Note’s objectives are twofold. First, the Note seeks to introduce these sources to the literature by providing an overview of the drafting instructions and guidance in the state bill drafting manuals. Because there has been little scholarly consideration of the state bill drafting manuals, I discuss their contents in detail in an effort to improve their circulation among scholars and future litigants, and to foster greater awareness of their potential utility in statutory interpretation. Second, the Note offers normative justifications for using drafting manuals in statutory interpretation as well as principles to guide state courts in considering drafting manuals in their jurisprudence.

This Note proceeds in four Parts. Part I provides background on state legislatures as institutions, focusing in particular on legislative drafting offices. Part II then examines the contents of the drafting manuals published by these offices and how these manuals guide drafters. Part III surveys cases in which state courts have considered and cited legislative drafting manuals and illustrates how these cases and manuals reveal an ongoing interbranch dialogue between state courts and legislatures. The conventions and instructions in the drafting manuals aim not only to align drafting practices horizontally within the legislative drafting offices but also to reflect the state judiciaries’ interpretive practices. State courts’ reliance on drafting manual provisions in statutory interpretation establishes vertical alignment between the legislative and judicial branches.

Part IV draws on these findings to propose a normative framework to guide state courts’ use of drafting manuals in statutory interpretation. Courts should use the drafting manuals in two ways: to employ the manuals’ context about drafting offices to analyze legislative history, and to examine the manuals’ drafting conventions in order to ascertain the meaning of the statutory text. Given the diversity of state legislatures and drafting offices, the context and circumstances of a particular state should guide the particulars of the analysis. The Note concludes with factors to help state courts determine how to use drafting manuals and how much weight to accord the manuals in statutory interpretation.

I. bill drafting in the state legislatures

The drafting manuals are both a product and practice of state legislatures. Although a majority of state legislatures use these manuals, it is difficult to speak of “state legislatures” as a whole because they are marked by tremendous diversity. This diversity manifests in a range of institutional characteristics. According to 2013 data, Alaska has the smallest state senate with twenty senators and Minnesota has the largest with sixty-seven senators.21 There is even greater variation in the size of the lower houses: Alaska has the smallest house of representatives with forty members, while New Hampshire has the largest with four hundred members.22 In some states, such as California, Pennsylvania, and New York, the occupation of state legislator is the time equivalent of at least eighty percent of a full-time job, and legislators are paid enough to make a living without outside income.23 In contrast, in other states, such as Montana, New Hampshire, and North Dakota, legislators spend about half of the time of a full-time job doing legislative work, and receive minimal compensation.24 Half of all state legislatures fall somewhere in between: legislators typically spend more than two-thirds of a full-time job doing legislative work and receive substantial compensation but usually not enough to make a living without another source of income.25 Moreover, the size of legislative staffs varies significantly across the country: as of 2015, the Vermont legislature had the smallest staff, with ninety-two permanent and session legislative staff, and the New York legislature had the largest, with 2,865 permanent and session legislative staff.26

State legislatures differ not only in size and structure, but also in the volume of their output. The number of bills introduced in the 2013 legislative term ranged from 308 in the Alaska legislature to 14,174 in the New York legislature.27 In similarly stark contrast, the number of bills enacted varied from forty-five in the Wisconsin legislature to 2,381 in the Illinois legislature.28

Despite these differences, every state legislature shares one key institutional feature: legislative drafting offices. These offices are staffed by professional, nonpartisan bill drafters who assist legislators in preparing legislation.29 Furthermore, a number of states have pre-filing requirements, which mandate that all proposed legislation be submitted to the state’s drafting office for review and processing before it is introduced in the legislature.30 Although the specifics of these pre-filing requirements differ by state, most stipulate that the drafting office should review the proposed legislation for elements such as format,31 technical correctness,32 and/or style.33

These legislative drafting offices vary in structure and capacity. Many of the offices offer not only bill-drafting services but also related legislative services—providing research on request to members of the state legislature,34 performing fiscal analyses of proposed bills,35 maintaining a legislative reference library,36 and preparing and arranging statutes for publication.37 While most state legislatures have one office that is responsible for bill drafting, two states in this study, Florida38 and Louisiana,39 have separate offices for the House of Representatives and the Senate. In addition, the Minnesota Revisor of Statutes provides bill-drafting services to both houses of the legislature and state agencies and departments,40 but both the Minnesota House and Senate also have their own offices that provide legal and research services.41 Legislative drafting offices vary not only in structure but also in size and capacity. Some offices have a small number of attorneys and support staff, such as the Montana Legislative Service Division, which has about fifty-five staff members.42 By contrast, other bureaus, such as New Jersey’s Office of Legislative Services, have more than 300 staff members.43

While every state has a legislative drafting office, the professional drafters in these offices do not write each and every bill introduced in the legislatures. Rather, statutory language may come from a variety of sources. In most states, drafters outside the drafting office may prepare bills. Wisconsin is the exception, since its state law requires that all legislation be prepared by the state’s Legislative Reference Bureau.44 Moreover, some state legislatures have partisan bill-drafting services for legislators in the Democratic or Republican Party. For example, Hawaii has separate research offices for the majority and minority of the House and Senate that provide legal research and drafting services to members of their respective political parties.45 Furthermore, professional bill drafters do not always draft legislation wholesale. Because similar issues often concern multiple states, bill drafters may borrow from statutes or bills of other states.46 In addition, bill drafters look to model acts, prepared by groups such as the American Law Institute (ALI), and uniform laws proposed by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL).47 Each state’s professional bill drafters play an important role, however, in adapting the “borrowed” statute—whether adopted from the law of another state, a model bill, or a uniform law—to conform to that state’s law, drafting practice, and style.48

Furthermore, some bills are prepared by drafters who are entirely outside the state legislature, known as “outside drafters.” For example, private law-making groups, known as Interested Private Lawmakers (IPL), which serve as the legislative arms of interest groups, draft model bills for state legislators to introduce.49 The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) is one of the most dominant IPLs, and describes itself as a “non-profit, nonpartisan association of over two thousand state legislators that works to promote principles of free markets, limited government and federalism throughout the states.”50 ALEC has written hundreds of model bills on a variety of issues. About one thousand bills based on ALEC model legislation are introduced annually in state legislatures across the country and, on average, twenty percent of these bills are enacted.51

The scant literature on the legislative process at the state level has not comprehensively assessed the number of bills in state legislatures authored by professional bill drafters as compared to outside drafters; resolving this issue is beyond the scope of this study, and these numbers likely vary across states and over time. However, it appears likely that state legislative drafting offices prepare many, but not all, of the bills introduced in state legislatures.

II. the legislative drafting manuals

Equipped with an understanding of the institutions that produce legislation at the state level, this Part turns to the sources of statutory meaning at the heart of this Note: the state bill drafting manuals. Many state legislatures have bill drafting manuals to assist in drafting legislation, and forty manuals from thirty-seven states52 are publicly available.53 This Part provides an overview of the types of drafting instructions and guidance in the drafting manuals in an effort to build greater awareness of the manuals among scholars and future litigants.

These manuals seek to help drafters prepare clear and uniform legislation.54 The drafting manuals establish conventions concerning language, style, and format to guide the bill-drafting process.55 As one manual explains, a drafting manual “serve[s] as a guide to the creation of an accurate, clear, and uniform legislative product” by establishing a shared legislative language and style.56 Such shared conventions are particularly useful for ensuring consistency “in instances where more than one style is considered correct or where the unique characteristics of legislative documents require a deviation from the generally accepted standards.”57 Furthermore, shared language and style not only impose order on the bill-drafting process, but also help ensure that new statutes are consistent with the existing statutes in the code.58 In this way, the manuals horizontally align drafting practices within drafting offices and legislatures.

Despite this common purpose, the scope and substance of the drafting manuals vary broadly. Most of these manuals are published by bill drafting offices; one, the Pennsylvania manual, is part of the state’s code.59 Almost all state legislatures have only one publicly available manual used to draft bills for both houses of the legislature; in two states, Florida and Louisiana, the drafting manuals are specific to each house of the legislature.60 Two other states, Maryland and Oregon, have more than one manual, with each manual addressing different aspects of drafting and the legislative process.61

The manuals differ considerably in length and level of detail offered to bill drafters. For example, the Tennessee drafting manual is only forty-eight pages long, while the Colorado manual has 598 pages. These manuals also have different audiences; some manuals serve as internal documents and are intended primarily for the professional drafters in the drafting offices,62 while other manuals are meant to guide anyone who helps prepare bills for the state legislature.63 Although all of the manuals include directions for professional bill drafters in the states’ legislative drafting offices, some manuals also include instructions specifically intended for outside drafters.64

Functional distinctions aside, the manuals are often substantively similar in the types of guidance that they offer to bill drafters. In particular, the drafting manuals’ provisions concerning background information for bill drafters, bill format and structure, and substantive drafting conventions overlap considerably. The survey that follows is not intended to be an exhaustive inventory of all of the information in the drafting manuals; rather, it focuses on common sections in the manuals in order to illustrate the types of guidance these manuals offer drafters. This Part describes provisions that are both typically included in the manuals and potentially relevant to courts and litigants interpreting statutes.65 Although each manual is unique, an examination of common manual provisions highlights the potential usefulness of these manuals to courts, scholars, and litigants faced with questions of state statutory interpretation.66

A. Background Information About the Legislative Drafting Offices

Many of the drafting manuals include background information about legislative drafting offices and bill-drafting processes.67 These sections have the potential to be relevant in statutory interpretation when it comes to contextualizing legislative history.68 They typically explain that the process begins when a legislator contacts the drafting office to request a draft of a bill addressing a particular topic.69 The professional drafters have an ethical obligation to keep these bill requests confidential.70 Furthermore, professional drafters often must refrain from partisan or political activity and remain neutral with regard to the policies involved in legislative work requests.71

Many manuals also explain that the role of the professional drafter is to convert the legislator’s request into statutory language in proper style and form to carry out the objectives of the bill’s sponsor.72 To ensure that a bill achieves such objectives, many manuals encourage drafters to discuss the bill with the sponsor during the drafting process.73 For drafting ideas, several manuals recommend that drafters consider other bills, including uniform laws, model acts, and the laws of other states.74 Most of these manuals stipulate, however, that in using these sources, drafters should conform the bill to the state’s own drafting style and form.75

B. Bill Format and Structure

In addition to providing background information about legislative drafting offices, almost all of the manuals instruct drafters how to format and structure bills.76 In particular, many manuals define the subunits of statutes, such as paragraphs, subsections, and subparagraphs, and explain how to reference these subunits.77 For example, the Maryland drafting manual describes the proper order of subdivision within a section in a statute (section, subsection, paragraph, subparagraph, subsubparagraph) and the proper numbering for each in order to ensure that a statute’s internal references are clear.78 These instructions may help interpreters understand statutory provisions that reference other subunits of the statute by clarifying the drafter’s understanding of what each particular subunit encompasses.79 For example, if a provision indicates that its applicability is limited to a specific paragraph, subdivision, or chapter, the drafters’ understanding of those terms would help determine the scope and reach of the statutory provision.

The vast majority of the manuals also include descriptions of the requisite elements of a bill, such as titles, short titles,80 and the enacting clause.81 Some manuals also establish clerical requirements for bills, instructing drafters of the proper paper and margins,82 font,83 spacing,84 and bill covers.85 While necessary, these instructions covering the mechanics of legislative boilerplate may only be relevant for statutory interpretation on the rare occasion.

C. Substantive Drafting Conventions

All of the drafting manuals surveyed in this study include substantive provisions directing the drafter to employ certain conventions in style, grammar, and word usage. These conventions are particularly relevant in statutory interpretation because they offer insight into the intended meaning of particular words and phrases in statutes. The substantive drafting conventions in the manuals include both (1) canons of construction, which are “a set of background norms and conventions” that “serve as rules of thumb or presumptions that help extract substantive meaning from, among other things, the language, context, structure, and subject matter of a statute”;86 and (2) linguistic and stylistic conventions.

The following discussion is not intended to be a comprehensive list of all of the drafting conventions in the manuals, but rather, focuses on commonly included conventions to illustrate the type of guidance the manuals provide. Many of the manuals broadly address the same recurring legislative drafting issues, and while the drafting conventions for addressing these issues largely overlap, states have adopted different approaches to certain issues. As a result, although the manuals include many of the same conventions—such as the use of present tense, active voice, and gender-neutral language—the substance of the conventions in the manuals of different states occasionally conflicts. In addition to different drafting conventions, the manuals also include different canons of construction, reflecting variation in the rules of statutory construction across states.87

1. Direct References to Canons, Precedent, and Code

In instructing bill drafters in style, grammar, and word usage, almost all of the manuals contain direct references to canons of construction, judicial precedents related to statutory interpretation, and legislated codes of construction. Thirty-eight of the manuals in this study discuss at least one canon, and these references are often supported by citations to codified rules of construction or precedent; Virginia is the only state whose manual does not reference such interpretive principles. These thirty-eight manuals vary significantly in the number of canons discussed. Some manuals include only one or two interpretive canons, and the discussion of these canons plays a minor role in the manuals’ guidance on drafting conventions. For example, the Alabama drafting manual only makes a brief reference to one canon.88 In contrast, other manuals include detailed discussion of a number of canons. Some of these manuals have separate sections listing canons used in that state,89 while others integrate the canons into a more general discussion of guidance for style and form.90

Through these references to canons of construction, the manuals are self-consciously “written in anticipation of judicial interpretation” and instruct drafters “on how courts are likely to interpret certain language.”91 The manual provisions citing the canons “reflect an awareness of statutory language as the object of the courts’ attention.”92 Furthermore, the manuals often advise drafters to prepare bills with these interpretive rules in mind. For example, the Florida Senate drafting manual recommends that drafters familiarize themselves “with the basic principles of statutory construction” in order “[t]o ensure that a law will be applied as the Legislature intends,” as “they predict how a court will interpret an act of the Legislature.”93 The Colorado drafting manual goes further, explaining that the legislature’s code of statutory construction is comprised of the sections of the Colorado code “that have the greatest effect on bill drafting.”94 These provisions reveal that drafters not only are aware of specific conventions of statutory interpretation, but are actually advised to prepare bills with these principles in mind. 95

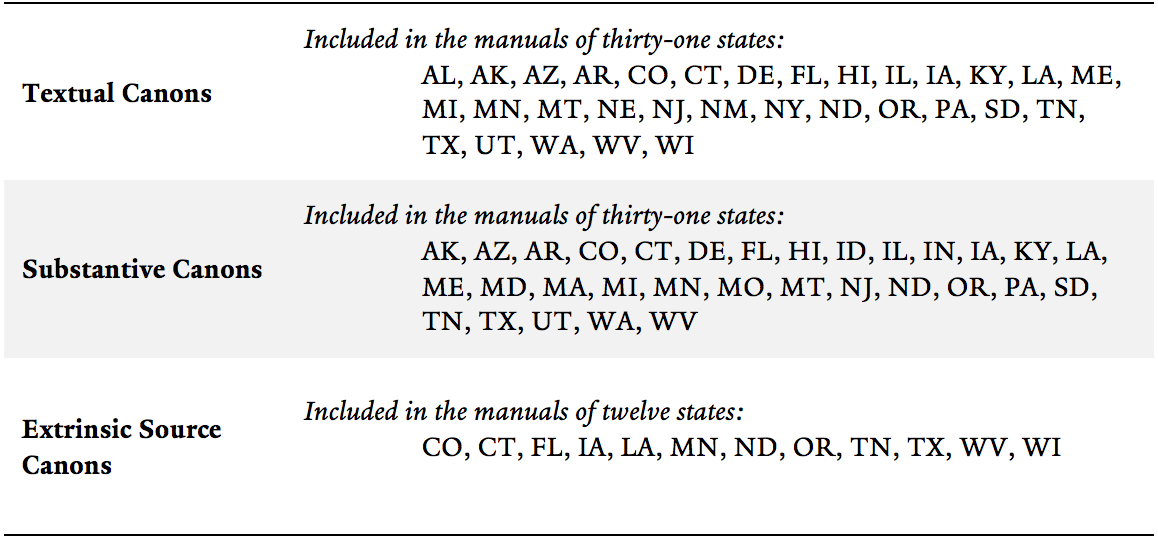

The following section describes some of the canons that are commonly included in the drafting manuals. In my analysis, I use the basic classification developed by William Eskridge, Philip Frickey, and Elizabeth Garrett: (i) textual canons, which include linguistic inferences, grammar and syntax rules, and textual integrity canons; (ii) substantive canons; and (iii) extrinsic source canons.96 Figure 1 encapsulates different states’ inclusion and exclusion of these three types of canons in their drafting manuals.

figure 1.

canons of construction in the drafting manuals

a. Textual Canons

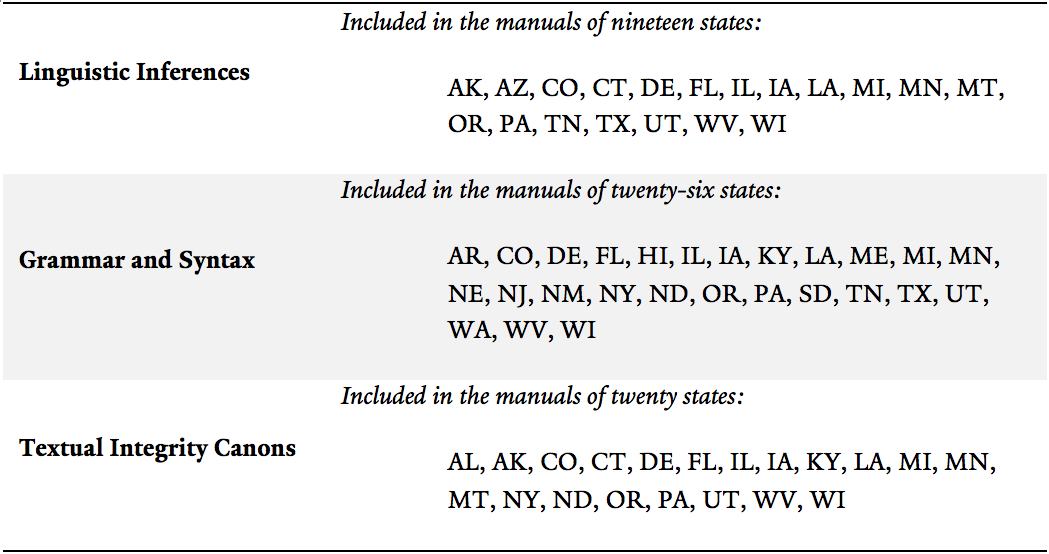

Thirty-one of the manuals surveyed discuss textual canons. Textual canons are discrete inferences “drawn from the drafter’s choice of words, their grammatical placement . . . and their relationship to other parts of the statute.”97 The textual canons discussed in the manuals include linguistic inferences, grammar and syntax rules, and textual integrity canons. Figure 2 summarizes the range of textual canons included in the manuals of the thirty-seven states.

The first category of textual canons, known as linguistic inferences, is included in nineteen manuals. Linguistic inferences attempt to provide “guidelines about what the legislature likely meant, given its choice of some words and not others.”98 The most commonly cited linguistic inference canon is the plain meaning rule, which directs courts to follow the plain meaning of the statutory text99 and is referenced in sixteen manuals.100 The manuals also discuss other inferential rules: eight manuals cite ejusdem generis,101 three manuals cite noscitur a sociis,102 and ten manuals cite expressio unius.103

In addition to linguistic inference canons, twenty-six manuals discuss canons related to grammar and syntax.104 These canons constitute presumptions that the legislature knows and follows certain “basic conventions of grammar and syntax.”105 For example, twenty manuals106 cite the singular/plural rule, which directs interpreters to construe “words importing the singular [to] include and apply to several persons, parties, or things,” and vice versa.107 Furthermore, fifteen manuals108 discuss the gender rule, which provides that masculine pronouns should be interpreted to include the feminine.109 In addition to grammar rules, a handful of manuals cite syntactical rules relating to referential and qualifying words. Six manuals,110 for example, refer to the rule of the last antecedent, which provides that “[r]eferential [or] qualifying words or phrases refer only to the last [word or phrase], unless contrary to the apparent legislative intent derived from the sense of the entire enactment.”111

The textual integrity canons are the last category of textual canons included in the manuals. These canons, referenced in twenty manuals, “clarify [statutory] meaning by focusing on the context of statutory language.”112 For example, the rule of consistent usage, which is cited in five manuals,113 provides that the same or similar terms in statutes should generally be construed in the same way.114 Seven manuals reference the rule against surplusage, another broad coherence-based canon.115 This canon provides that interpreters should avoid interpretations of statutes that would render provisions of an act superfluous or unnecessary.116 A second type of textual integrity canon defines which parts of the published code are relevant to interpreters. For example, seven manuals discuss interpretive rules addressing whether interpreters may consider section headings in the construction of a statute.117 The Colorado and Pennsylvania drafting manuals advise drafters that under each state’s interpretive rules, courts may consider section headings in construing a statute.118 Five other manuals, however, indicate that section headings are not part of the statute and may not be considered in statutory construction.119 Another textual integrity canon concerns whether interpreters may consider a statute’s statement of purpose and preamble in discerning statutory meaning: thirteen manuals indicate interpreters may consider the statement of purpose and preamble, while the manual of one state, Kentucky, stipulates that the statute’s statement of purpose and preamble are not considered part of the act.120

figure 2.

textual canons in the drafting manuals

b. Substantive Canons

While the textual canons provide interpretive inferences based on the words, phrases, and structures of the statutory text itself, the substantive canons instruct interpreters to consider larger public values and policies in interpreting statutes.121 The drafting manuals of thirty-one states discuss at least one substantive canon.122 By far the most common substantive canon included in the manuals is the severability canon, which is a presumption in favor of severing unconstitutional provisions and leaving the valid parts of the statute in force. Twenty-nine manuals from twenty-eight states reference this canon.123 Moreover, most state codes codify severability,124 and twenty-two manuals refer to the state code’s general severability clause.125 Not all states, however, follow this approach. The Utah drafting manual notes that the Utah Code does not have a general severability clause addressing whether a statutory provision is to be severed if a court finds a portion of the law unconstitutional or invalid.126 Apart from legislated severability provisions, ten manuals also discuss the judicial presumption in favor of severability.127

In addition to the severability canon, seventeen manuals discuss state retroactivity rules, which address when a statute can be applied retroactively to past conditions.128 These states have slightly different formulations of the retroactivity rule: the rules cited in six manuals stipulate that no statute is retroactive unless expressly declared therein, while the other eleven manuals cite rules indicating that a statute will not apply retroactively absent contrary legislative intent.129

Although the severability and retroactivity canons are the most frequently cited substantive canons, some manuals cite other substantive canons relating to constitutional considerations. For example, six manuals cite the constitutional avoidance canon,130 and six manuals reference the rule of lenity, which requires that ambiguity in penal statutes be resolved in favor of the defendant.131

c. Extrinsic Source Canons

The final category of canons in the manuals is the extrinsic source canons. These rules of interpretation address how and when to consult sources outside the text of the statute itself to discern statutory meaning.132 For example, some extrinsic source canons explain how interpreters should construe statutes in reference to the common law.133 One manual cites precedent indicating that statutes are presumed not to alter the common law; two manuals explain that statutes in derogation of the common law are narrowly construed; and two manuals reject the derogation of common law canon.134 In addition to the common law, some of the extrinsic source canons included in the manuals direct interpreters to construe statutes in light of other statutes.135 For example, seven manuals136 discuss the in pari materia canon,which instructs interpreters to interpret statutes employing the same terminology or pertaining to the same subject matter similarly.137

Some of the manuals also include extrinsic source canons concerning when interpreters can consider legislative context, including legislative history and statutory history.138 The substance of the canons cited varies across states, depending on the interpretive rules adopted by each state’s legislature and judiciary. For example, five manuals indicate that courts can consider legislative history if the statute is ambiguous; two manuals provide that courts can consider legislative history whether or not the statute is ambiguous; and one manual explains that courts ordinarily should not consider legislative history, except as support for conclusions following from established rules of statutory construction.139 Other canons encourage interpreters to consider judicial readings of the statute at issue. For example, the reenactment rule, cited in five manuals,140 stipulates that when a statute is amended, the judicial construction previously placed upon the statute is deemed approved to the extent that the provision remains unchanged.141 One manual cites a related canon, the acquiescence rule, which provides that legislative inaction after judicial interpretation of a statute may indicate legislative approval of that interpretation; 142 this manual, however, cites precedent indicating that legislative inaction is a “weak reed” to rely on in determining legislative intent.143

2. Implied and Restated Conventions

All of the manuals surveyed direct drafters to employ certain conventions in the language and structure of a bill. Compared to the provisions discussed in Section II.C.1, these provisions describe substantive drafting conventions without naming canons or specific interpretive rules. These conventions aim to promote accurate, clear, and uniform legislation by establishing a shared language and style to impose order on the drafting process.144

a. Style and Grammar

All of the manuals surveyed include conventions with general style and grammar instructions to minimize ambiguity in statutory language and to ensure consistency across statutes in the code. Almost all of the manuals direct drafters to write bills in a simple and clear style; in particular, the manuals instruct drafters to use plain language, simple sentence structure, and concise provisions.145 For example, the Montana drafting manual explains that “[g]ood drafting requires concise wording that is understandable by a person who has no special knowledge of the subject.”146

Some of these style and grammar conventions restate the canons and interpretive rules used by courts in construing statutes. For example, thirty-six manuals from thirty-five states advise drafters to be consistent in their use of language throughout the bill.147 The Alaska drafting manual is typical. It cautions drafters, “Do not use the same word or phrase to denote different things or different words or phrases to denote the same things. Be consistent.”148 This convention essentially rearticulates the core principle underlying the rule of consistent usage without saying as much.

Other style and grammar conventions are related to, but not identical to, the canons. For example, thirty-two manuals from thirty-one states instruct drafters on whether to draft bill provisions in the singular or the plural.149 Many of these manuals advise drafters to use the singular instead of the plural when possible.150 The Delaware drafting manual justifies its preference for the singular by explaining that “the singular is clearer than the plural” and that “[a] statute is intended to speak to each person who is subject to it and should be drafted that way.”151 Although some of these provisions also cite the interpretive rule that the singular includes the plural,152 these rules differ because they offer affirmative instructions that drafters should follow in preparing bills. Other discrete style and grammar conventions are part of almost all of the manuals surveyed, such as instructions concerning the use of gender-based pronouns and gender-neutral language,153 capitalization rules,154 punctuation rules,155 the active voice,156 and the present tense.157

In addition to conventions focusing on discrete style issues, the manuals also include instructions concerning broader grammatical and structural issues. For example, twenty-nine manuals from twenty-eight states instruct drafters on how to structure exceptions or limitations to the applicability of statutory provisions.158 Most manuals direct drafters on the appropriate language used to introduce exceptions; many stipulate that drafters should avoid the use of provisos, such as subclauses beginning with “provided that.”159 Many also instruct drafters on where to place exceptions within subsections and individual sentences.160 The Indiana drafting manual is typical of the type of advice the manuals provide drafters concerning exceptions and limitations. It indicates that

[l]imitations or exceptions to the coverage of a legislative measure or conditions placed on its application should be described in the first part of the legislative measure . . . . If the limitations, conditions, or exceptions are numerous, notice of their existence should be given in the first part of the legislative measure, and they should be stated separately later in the legislative measure.161

The manual further indicates that “[i]f a provision is limited in its application or is subject to an exception or condition, it generally promotes clarity to begin the provision with a statement of the limitation, exception, or condition or with a notice of its existence.”162 Finally, the manual instructs drafters on the proper phrases to express limitations and explains the different uses of “if,” “when,” and “whenever.”163

About half of the manuals also include guidance on the use of modifiers.164 Most of these manuals explain that misplaced modifiers often lead to ambiguity in statutory provisions; the Texas drafting manual even notes that “[p]oor placement of modifiers is probably the main contributor to ambiguity in statutes.”165 These manuals typically instruct drafters on the proper placement of modifiers in sentences,166 cautioning drafters to be careful that they modify only the words that they intend to modify.167

b. Use of Particular Words

Almost all of the manuals include conventions relating not only to style and grammar but also to the use of particular words. These provisions seek to impose order by promoting consistency and uniformity in how certain words are used in statutes. As the Colorado drafting manual notes, “[w]hen a word takes on too many meanings, it becomes useless to the drafter.”168

For example, thirty-three manuals from thirty-two states advise drafters on the use of “shall” as opposed to “may”: the former indicates that something is mandatory while the latter is permissive and confers a privilege or power.169 The Arizona drafting manual explains why drafters must pay close attention to the use of these terms: “A prime drafting concern is to preserve the distinction between mandatory and permissive directives. The inconsistent or inaccurate use of ‘shall’ and ‘may’ has occasionally allowed judicial selection rather than legislative direction to determine the applicable verb form in laws.”170 Several manuals further explain how drafters can prohibit an act through the use of “shall not” and “may not.”171 Others explain when the use of other similar terms, such as “must,” is appropriate.172

In addition to “shall” and “may,” many manuals explain the distinction between “that” and “which” and when it is appropriate to use each term.173 The Colorado drafting manual is typical: “‘That’ indicates a restrictive clause that restricts and defines the word modified and that is necessary to identify the word modified. A restrictive word, clause, or phrase is necessary to the meaning of a sentence and is not set off by commas.”174 In contrast, the Colorado manual explains, “‘Which’ indicates a nonrestrictive clause that does not restrict the word modified and that provides additional or descriptive information about the word modified. A nonrestrictive word, clause, or phrase is not essential to the meaning of a sentence and is set off by commas.”175 Thirteen manuals also include conventions for expressing conditions, in particular through the use of words such as “if,” “when,” “where,” and “whenever.”176 For example, the North Dakota drafting manual directs drafters to use “if” to designate “a condition that may never occur”; “when” for “a condition that is certain to occur”; “whenever” for a condition that “may occur more than once”; and “‘where’ only regarding place.”177

D. Key Takeaways

In sum, there is considerable overlap in the type of guidance included in the publicly available drafting manuals. Most of the manuals provide information about the bill-drafting process and the role of the professional drafter in that process. Furthermore, almost all of the manuals include instructions concerning bill format and structure, and all of the manuals surveyed contain conventions for style, grammar, and the use of particular words. The manuals include these drafting conventions in an effort to create a shared language and style for legislation.178 Moreover, the institutionalization of bill-drafting practices in drafting manuals suggests that legislatures are attempting to cement certain patterns and practices to last over time—regardless of who is in power and their attitudes toward statutory interpretation and legislative drafting. Accordingly, the conventions reflect a key goal and function of the drafting manuals: to impose order on the drafting process to ensure that legislation within the state’s code is clear and uniform.179

The frequent inclusion of the canons of construction in the drafting manuals has significant implications for bill drafting as well. Of the manuals surveyed, thirty-eight discuss at least one canon of construction.180 A wide variety of canons are included in the drafting manuals, and most of the manuals surveyed discuss both substantive and textual canons.181 In most state legislatures, there is an effort to inform bill drafters of some of the interpretive principles used by the state’s judiciary so that the drafters can prepare legislation with those principles in mind.182 This finding deflects common scholarly skepticism about the utility of canons and, particularly, frequent doubts about canons’ significance, at least at the federal level.183 Indeed, the survey suggests that the canons may serve a different—and more salient—role at the state level in both drafting and interpretation.

Drafting manuals serve as mechanisms for the legislatures to promote clarity and uniformity in anticipation of judicial interpretation. In so doing, they comprise half of an interbranch dialogue. As the next Part demonstrates, state courts’ use of these manuals in the process of statutory construction leads to a two-way conversation between legislatures and the courts.

III. legislative drafting manuals in the state courts

By offering insights into the legislative process and drafting norms, these manuals help courts understand the intended meaning, purpose, and text of any given bill. And state courts have, in fact, turned to drafting manuals when faced with difficult questions of statutory interpretation.

The drafting manuals are a unique source for statutory interpretation. They are an extrinsic aid for interpretation as they are “sources outside the text of the statute being interpreted.”184 Some of the most well-known types of extrinsic sources are the common law, legislative history, and other statutes,185 but the drafting manuals bear obvious differences from these sources. They are neither sources of law nor prepared with reference to any particular statute. Instead, the drafting manuals are akin to other general reference sources that are used in statutory interpretation, such as dictionaries and grammar books, because they contain guidelines for the use of language and grammar in writing.186 Therefore, the drafting manuals could assist interpreters in “ascertaining the ‘common and accepted meaning’ of words and phrases” in a state’s code.187

Unlike dictionaries and grammar books, however, the drafting manuals are sources produced by the legislatures themselves. As a result, they shed light on the shared understandings of the bill drafters. The manuals’ discussion of drafting conventions concerning style, grammar, and the use of particular words “reveal[] the standards and definitions relied on by those who choose and arrange the words, phrases and punctuation” found in statutes.188 Moreover, the inclusion of canons of construction in the drafting manuals indicates how drafters expect the words and phrases in their bills to be interpreted by courts. Unlike dictionaries and grammar books, the drafting manuals are not merely sources for discrete rules and conventions concerning grammar and style. Because the manuals also discuss the rules, practices, and procedures governing legislative drafting offices, they offer insight into how these offices function as institutions.

In this Part, I survey cases in which state courts have used the drafting manuals in statutory interpretation. These cases demonstrate an interbranch dialogue between state courts and legislatures: not only are the manuals written self-consciously “in anticipation of judicial interpretation,”189 referring to the judiciary’s precedent and canons of interpretation, but the courts also cite the manuals to ascertain statutory meaning. Not only do the drafting manuals strive to align drafting horizontally by establishing shared conventions for bill drafters, but with the aid of the judiciary, the manuals also create shared vertical conventions. That is, the drafting manuals incorporate judicial practice, and by referencing the manuals, the courts take into account the legislative process. As Part IV discusses, this interbranch dialogue furthers democratic and rule-of-law values, and thus legitimizes the courts’ use of the canons of interpretation and drafting conventions in the manuals.

A. Current State Court Practices

All of the drafting manuals surveyed instruct drafters to employ certain conventions in language, style, and grammar,190 and several state courts have referred to these conventions to help determine statutory meaning. For example, in Johnson v. Johnson,191 the Supreme Court of Iowa consulted a provision in the Iowa drafting manual concerning the use of the singular and plural. The relevant statute provided that “[t]he owner and operator of an all-terrain vehicle . . . is liable for any injury or damage occasioned by the negligent operation of the all-terrain vehicle.”192 The main issue in the case was whether the statute could impose liability on both the vehicle owner and its operator. The trial court reasoned that it would be grammatically incorrect to use “is liable” rather than “are liable” when referring to both owners and operators, so the statute was ambiguous and should be construed to impose liability only on the vehicle operator.193 In its analysis, the Supreme Court of Iowa relied on the Iowa drafting manual to reverse the trial court. After consulting the manual’s guidance that “the singular incorporates the plural, and the plural incorporates the singular,” the court concluded the statute was not ambiguous and imposed liability on both the vehicle owner and the operator.194 The reasoning in this case is significant because the Iowa Supreme Court drew from a convention employed by the legislature—as evidenced by the citation to the drafting manual—to reverse what would otherwise have been a reasonable interpretation of text, and thus helped to save the statute from an interpretation that would have been contrary to legislative intent. In other cases, state courts have relied upon manual provisions concerning style and grammar, such as instructions concerning the placement of modifiers,195 consistency in the use of language throughout a bill,196 superfluous statutory definitions,197 and punctuation.198

Courts have also referenced the manuals’ instructions concerning the use of particular words to help determine statutory meaning. In State v. Powers,the Wisconsin Court of Appeals referenced the Wisconsin drafting manual’s conventions concerning the use of “means” and “includes.”199 The statute at issue covered sexual assault committed by an employee of an “inpatient health care facility,” and the court was tasked with determining whether the statutory definition of that term was exhaustive.200 According to the relevant statutory provision, inpatient health care facility “means any hospital nursing home, county home, county mental hospital or other place licensed or approved by the department.”201 The court consulted the Wisconsin drafting manual, which directed bill drafters to employ the term “means,” rather than “includes,” whenever enumerated items in a definition are intended to render the definition complete, and concluded that “inpatient health care facilities” are limited to the facilities specifically identified in the statutory definition.202 By referring to and citing the state’s drafting manual, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals self-consciously drew from a convention employed by the legislature to ensure that its interpretation of the statutory definition was consistent with the legislature’s intended meaning. In other cases, state courts have also referred to manual conventions for the distinction between permissive and mandatory terms,203 conjunctive and disjunctive terms,204 in addition to the distinction between “means” and “includes.”205

In addition to conventions concerning language and grammar, state courts have also considered instructions from drafting manuals as to how to format and structure bills. As Section II.B described, almost all of the drafting manuals contain instructions for bill format and structure, which help interpreters understand statutory provisions that reference other subunits of the statute. For example, in Nichols v. Progressive Northern Insurance Co., the Supreme Court of Wisconsin used the state’s drafting manual to interpret a statute that prohibits an adult from “knowingly permit[ting] or fail[ing] to take action to prevent the illegal consumption of alcohol beverages by an underage person on premises owned by the adult or under the adult’s control.”206 The statute further stipulated that “[t]his subdivision does not apply to alcohol beverages used exclusively as part of a religious service.”207 In addressing which parts of the statute were included in the “subdivision,” the court relied on the definition of the term in the Wisconsin drafting manual.208 The Wisconsin Supreme Court thus relied on the state drafting manual to interpret the statute in light of the drafter’s understanding of what the particular subunit at issue would encompass. In addition to the Supreme Court of Wisconsin,209 courts in Ohio210 and Maryland211 have also looked to manual provisions concerning bill format to construe the meaning of internal statutory references.

A handful of other state courts have cited the other types of manual provisions discussed in Part II, namely, background about the legislative drafting offices and the canons of construction. Most of the drafting manuals include sections with background information about the legislative drafting office and bill-drafting process; these manual provisions typically explain the role of the professional drafter in preparing the bill and the relationship between the bill drafter and the sponsoring legislator.212 If a court resolving a statutory question is interpreting legislative history from the bill-drafting process, such context about the drafting office can help the interpreter understand the legislative history. For example, in In re Termination of Parental Rights to Quianna M.M., the Wisconsin Court of Appeals was tasked with determining whether a statute that established “parenthood as a result of sexual assault” as grounds for involuntary termination of parental rights applied to all parents or fathers only.213 The Wisconsin Court of Appeals examined a memorandum from the bill’s sponsor to a drafter in the Legislative Council staff directing the drafter to amend the grounds for involuntary termination created in the bill “to make them apply to fathers only.”214 In analyzing this part of the legislative history, the court cited the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau’s (LRB) drafting manual’s directive that drafters “should not and cannot make the basic policy decision for the requester.”215 The court reasoned that because the statutory language was based on a request from a legislator and “would not have been [the drafter’s] idea,” the provision in question applied to fathers only.216 The court thus used the drafting manual’s rules concerning the function of the professional drafter to interpret the statute’s legislative history by distinguishing the role of the sponsor from that of the drafter.

State courts have also cited to the final category of manual provisions: the canons of construction. Two judicial opinions from Maine have cited the Maine drafting manual’s discussion of the retroactivity canon in justifying their use of that canon as a reasonable approximation of legislative intent.217 For example, in Greenvall v. Maine Mutual Fire Insurance Co., the legislature had amended the relevant statute to increase the amount recoverable, but only after the cause of action accrued, and the court had to determine whether to give this amendment retroactive effect.218 To make this determination, the court relied on the retroactivity canon and in its analysis, referenced the Maine drafting manual to explain that the judicial presumption against implied retroactivity “reasonably assumes that the Legislature is capable of making clear its intent that a statute be applied retroactively.”219 The court thus used the fact that the state drafting manual included the retroactivity canon to bolster its own reliance on the canon.

These cases in which state courts reference legislative drafting manuals are significant because they demonstrate interplay and dialogue between state courts and legislatures. As discussed in Part II, the drafting manuals aim to create a shared language and style for bill drafters, thus establishing horizontal alignment of bill drafting within the state legislative drafting offices. The cases in which courts reference the drafting manuals, however, indicate that the manuals can also serve as a vehicle for vertical alignment between the state legislature and judiciary.

B. Interplay Between State Courts and State Legislatures

By using drafting manuals, these courts aim to construe statutes in accordance with how legislatures actually draft—both in terms of the rules and procedures of the drafting offices as well as the drafters’ shared conventions concerning style, grammar, and bill format. Furthermore, at least some courts have considered the drafters’ awareness of a particular canon of construction in determining whether to employ that canon in resolving the statutory question at issue.

The legislative drafting offices are active participants in this dialogue. The drafting manuals indicate that shared drafting conventions are formulated in light of the judiciary’s interpretive practices. The inclusion of the judiciary’s interpretive principles in the manuals reflects an awareness of statutes as the subject of judicial interpretation.220 The manuals thus instruct drafters to prepare legislation with the basic principles of statutory construction in mind “[t]o ensure that a law will be applied as the Legislature intends” since these principles “predict how a court will interpret an act of the Legislature.”221

IV. guiding principles for the use of drafting manuals in statutory interpretation

Yet this dialogue remains largely unseen. While several state courts have illustrated just how these drafting manuals could be used in questions of statutory interpretation, these manuals are not yet a part of standard judicial practice. Indeed, even if courts were to recognize the interpretive power of these manuals, they would lack a theory of how these manuals should be incorporated into the project of statutory interpretation.

As this Part argues, because the drafting manuals facilitate interbranch dialogue between state courts and legislatures, judicial reliance on the drafting manuals is normatively desirable. When courts construe statutes in light of manual provisions that reveal drafting practices, courts can better align their interpretive principles with how the legislature actually drafts bills. As a result, this practice helps an interpreting court serve as the “faithful agent” of the enacting legislature and promotes democratic legitimacy. From a rule-of-law perspective, the drafting manuals can serve as devices for the legislature and judiciary to coordinate their practices such that courts will apply legislation uniformly and predictably.

This Part then offers a framework to guide courts in operationalizing these broad benefits of using drafting manuals in statutory interpretation. I suggest the types of guidance from the manual provisions described in Part II would be most valuable to courts and when and how courts should use these provisions. Specifically, courts should use information about the drafting offices’ practices and procedures to help analyze the legislative history of statutes that originate in those offices. Courts should also employ the drafting manuals to help ascertain the meaning of particular words and phrases in statutes. Three types of guidance in the manuals can assist interpreters in this second task: (i) provisions for the format and structure of bills; (ii) conventions concerning style, language, and the use of particular words; and (iii) the canons of construction. Due to the tremendous diversity in state legislatures and legislative drafting offices, however, the weight a state court accords to a drafting manual should depend on the context of that particular state. I conclude with state-specific considerations to direct courts as they assess how to use the drafting manuals in statutory interpretation.

A. Normative Justifications

The judicial use of drafting manuals in statutory interpretation serves two important values: democratic legitimacy and rule of law. Because the drafting manuals offer insight into how legislatures actually operate and the intended meaning of certain words and phrases, judges can use the manuals to align their interpretive principles with drafting practices. Interpretive alignment reinforces the role of judges as the “faithful agents” of enacting legislatures. Moreover, because the drafting manuals represent coordinating devices that help state courts and legislatures align their practices, the manuals help ensure that legislation will be applied in a uniform and predictable manner.

1. Democratic Legitimacy

In a representative democracy, the people participate in day-to-day governance only indirectly, by electing representatives who enact laws that reflect their preferences, and this notion of representative democracy is integral to the legitimacy of our statutes.222 Because these elected representatives are the political actors tasked with enacting statutes, and these statutes are thought to reflect the public’s preferences, legislatures have a strong claim to democratic legitimacy, and courts interpreting statutes should serve as the “faithful agent” of the enacting legislature by striving to implement the legislature’s intent. 223 Accordingly, if courts employ principles of interpretation that “faithfully reflect the preferences of those representatives (and, indirectly, of the citizenry as well), those rules have a strong claim to legitimacy on the basis of the democratic values they serve.”224 This “faithful agent” model is the guiding paradigm of many mainstream statutory interpretation theories and doctrines.225 Indeed, as one scholar noted, “[t]he view that federal courts function as the faithful agents of Congress is a conventional one,” and even as scholars and jurists have debated theories of statutory interpretation, the disputes focus on how best to implement the “faithful agent” paradigm, rather than the propriety of the paradigm itself.226

A state legislature’s drafting manual provides a relatively reliable source of information about how the enacting legislature prepared the statute. The offices responsible for drafting legislation actually produce these manuals, which describe the procedures and rules governing those offices. Moreover, the drafting manuals instruct drafters on specific conventions about style, grammar, and the use of certain words, and thus offer insight into the intended meaning of particular words and phrases. Professional drafters write and consult these manuals to guide the bill-drafting process and to ensure that legislation is drafted with a uniform style and form,227 so they offer a reliable source for the drafters’ shared conventions. The drafting manuals can also reinforce the courts’ use of the canons, many of which are based on assumptions about how the legislature drafts.228 Accordingly, drafting manuals can help interpreters understand whether these presumptions align with actual practices because the inclusion of a canon in a manual suggests that the drafters were aware of that interpretive rule and drafted with it in mind.

Interpreting statutes in light of the preferences and guidelines used by the bill drafters can help align statutory interpretation with the actual practices of legislative drafting and is desirable from a democratic legitimacy perspective. The use of the drafting manuals is particularly appealing given that judges are usually uncomfortable admitting to “lawmaking” in the statutory context.229 If interpreters subscribe to the ideal of legislative supremacy and believe that courts should not single-handedly establish interpretive doctrines, taking account of the drafting manuals ensures that courts’ interpretive presumptions do no more than reflect what the legislature actually does. While the legislative process is too complex to be fully reflected in statutory interpretation doctrines,230 using the manuals enables courts to align the practice of statutory interpretation with the functioning of state legislatures in a relatively efficient manner. Scholars have contended that the use of empiricism about legislative practices in statutory interpretation poses significant challenges—namely, that the relevant empirical questions are “unanswerable . . . at an acceptable cost or within a useful period of time.”231 The manuals help courts cross this hurdle by providing first-hand information about the drafting process in a form that is readily available to courts and litigants.

A potential counterargument to the use of drafting manuals in statutory interpretation is uncertainty as to whether these manuals inform actual drafting in practice. Although empirical research has yet to uncover the extent to which state bill drafters actually rely on the manuals in preparing legislation, a number of indicators suggest that manuals play an active role in bill drafting in the state legislatures. For example, some states require, either by statute or legislative rule, that all bills and resolutions be in the form and style prescribed by the state’s drafting manual.232 Similarly, several state legislatures require that all proposed legislation be submitted to the legislature’s drafting office for review of format, technical correctness, and/or style.233 In addition, many of the drafting manuals are updated annually,234 which suggests they are documents that are actively used by drafters.

At a broader level, however, the drafting manuals and the principles contained therein are important regardless of the empirical question of whether most bills are drafted with them in mind. The drafting manuals are institutionally significant as they aim to set forth a set of shared conventions in an attempt to standardize legislative style.235 From this perspective, the manuals seek to constrain the practices of bill drafters and provide notice of the general drafting principles and conventions to which they are expected to conform. The manuals may also establish the bounds of judicial interpretation by giving courts a sense of the rules that the legislatures have set for themselves when it comes to drafting bills.

2. Rule-of-Law Values

The use of drafting manuals to decipher statutory meaning also furthers rule-of-law values. From a rule-of-law perspective, statutes should “be applied in an objective, consistent, and transparent way to citizens and others subject to the state’s authority” so that they will be able to predict how statutes will be applied.236 Theorists have long debated whether doctrines of statutory interpretation—particularly the canons of construction—generate greater objectivity and predictability in statutory interpretation.237 Critics argue that the canons do not promote rule-of-law values because the canons are internally inconsistent and fail to constrain the discretion of judges interpreting statutes.238 Furthermore, because courts do not use the canons in a predictable and consistent manner, scholars contend, they do not force legislatures to draft statutes with care and clarity.239

The drafting manuals mitigate the urgency of these concerns by highlighting one reason for using the canons and traditional doctrines of interpretation: because legislatures do so. Insofar as interpretation is the practice of divining what legislatures actually did, there is no better guide than these manuals. Indeed, these manuals promote interbranch dialogue between the legislature and the judiciary and thereby improve coordination, uniformity, and predictability. The publication of the drafting manuals reflects an effort to make the bill-drafting process more transparent. Courts should take this opportunity to align their interpretive practices with the conventions actually employed in legislative drafting, as doing so would promote predictability and uniformity in both the application and interpretation of statutes. Moreover, the drafting manuals strive to make style and form uniform throughout a state’s code. Interpreting statutes in light of these drafting conventions would further this goal. In addition, the inclusion of canons in the manuals indicates that bill drafters are trying to prepare statutes in light of the interpretive practices of the state’s judiciary; the drafting offices in at least thirty-seven states have tried to guide drafters to prepare legislation with the judiciary’s interpretive principles in mind. From this perspective, the manuals can be viewed as coordinating devices that are attempting to put the legislatures and courts on the same page.

A rule-of-law-based critique of using the drafting manuals in statutory interpretation might claim that it is “unlikely that legislators or the general public consult them in order to understand a bill.”240 However, as discussed earlier,241 there are several indicia that the manuals retain an active role in the process of bill drafting. Moreover, the majority of state legislative drafting offices have made their drafting manuals available to the public, and efforts are underway to foster greater awareness of the manuals. In the world of practice, the National Conference of State Legislatures links to many of the drafting manuals on its website.242 In the realm of scholarship, Tamara Herrera recently published an article examining the Arizona Legislative Council’s drafting manual,243 and this Note sheds light on the remaining state drafting manuals.

B. Framework for State Courts in Considering Legislative Drafting Manuals

Having considered the general advantages of using the drafting manuals in statutory interpretation, I turn to specific principles that can guide state courts as they consider how to use drafting manuals in interpretation. I begin by examining specific types of provisions in the drafting manuals that could aid interpreters in resolving statutory questions. Because state legislatures and drafting offices vary tremendously, however, the weight a state court accords to a particular drafting manual provision should depend on the context of that particular state. I conclude with key considerations to guide this analysis.

1. Potential Uses of the Manuals

Courts can use the drafting manuals for two broad purposes: (a) offering guidance on the meaning of particular words and phrases in statutes, and (b) providing context about the legislative drafting offices to understand legislative history.

a. Ascertaining Statutory Meaning

First, state courts should use the drafting manuals to ascertain statutory meaning. Provisions in drafting manuals guiding drafters on how to format and structure bills are valuable because statutes frequently include internal cross-references to other subunits of the same statute. As illustrated in Paul v. Skemp and the other cases discussed in Section III.A, these manual provisions can clarify the significance of these internal cross-references for interpreters. In addition, courts should reference the conventions in drafting manuals concerning grammar and style. These manual provisions are valuable tools for statutory interpretation, offering insight into the shared understandings of those who draft legislation. As a result, these conventions can illuminate the intended meaning of a seemingly ambiguous statutory provision. A number of state courts have already used the drafting manuals in these two ways, and in light of the normative justifications for these uses, discussed in Section IV.A, courts across the country should continue and expand these practices.

Despite the fact that state courts do not yet frequently cite the manuals’ discussion of canons,244 they should. In light of the interbranch dialogue, the existence of a canon in a manual provides a reliable indication of intended statutory meaning. Many of these interpretive principles are based on presumptions about how the enacting legislatures draft statutes.245 For example, the textual canons are meant to reflect legislative practices,246 such as the presumption that legislatures use the same term consistently throughout a statute.247 Moreover, some extrinsic sources and substantive canons have traditionally been thought of as assumptions about legislative practices. For example, “[t]he reenactment rule assumes that if a legislature reenacts a statute without making any material changes in its wording, the legislature intends to incorporate authoritative agency and judicial interpretations of th[at] language into the reenacted statute.”248 The constitutional avoidance canon presumes that the legislature does not intend to draft unconstitutional statutes.249 In turn, the drafting manuals reference the canons to instruct drafters on how courts are likely to interpret certain language so that drafters can prepare bills with these principles in mind.250 The inclusion of a canon in the drafting manual used by the drafter thus indicates that the bill was actually prepared with an awareness of that principle.251 Citing to a canon in a drafting manual is not merely lip service—it reflects the idea that the presumptions underlying the canons are in line with actual practices. The inclusion of a canon in a drafting manual reinforces the legitimacy of a court’s use of that canon.

A related issue is how courts should treat the absence of a canon of construction from the drafting manual: if a drafting manual lists only some canons, should courts employ a canon not included in the manual? The exclusion of a canon casts doubt on whether the court should use that canon as a presumption of legislative practice, since there may be little evidence that the bill was drafted with that principle in mind. This seems particularly likely if the manual has a comprehensive list of the state’s interpretive principles.252 Courts may still wish to employ these canons of interpretation for other reasons. For example, the courts could use a canon to send a signal to the legislature253 or to advance a public value or norm.254 However, judges should acknowledge the source and function of their interpretive principles when the evidence from the drafting manuals indicate they are not coming from the actual legislative process.255

Another relevant inquiry is how a state court should consider the canons included in the state’s drafting manual in light of that state’s legislated code of interpretation. Every state legislature has enacted statutes that set forth rules of construction to govern how courts in that state resolve questions of statutory interpretation.256 In some respects, the drafting manuals are similar to these legislated rules of construction: both the manuals and the codes of construction demonstrate legislative awareness and approval of certain interpretive principles employed by the judiciary. However, the codes of construction and the drafting manuals are aimed at different audiences. The legislated codes of construction are intended for use by the state courts, and each indicates how the state legislature intends the judiciary to interpret its statutes.257 These codes thus represent an effort to guide and direct the judiciary’s interpretive doctrines. In contrast, the drafting manuals are published by the legislative drafting offices and intended for use by the professional bill drafters within those offices. The drafting manuals include canons of construction in an effort to instruct drafters about principles employed by the state’s judiciary so they can draft legislation more effectively.258 The manuals reflect the dialectic between the two branches. An interpreting court should consider both sources in determining whether to apply a particular canon in a statutory case. If a canon has been codified by the state legislature and is discussed in the state’s drafting manual, the inclusion in the manual reinforces the use of this canon because it indicates the statute was actually drafted with this principle in mind. If a canon is not part of a state’s code of construction, but is included in that state’s drafting manual, then it is still relevant for a state court to consider that canon because it is part of the enacting legislature’s drafting practices.

b. Providing Context About Legislative Drafting Offices

Interpreters should also use the information in the drafting manuals to better understand a bill’s legislative history.259 This is an extension of Victoria Nourse’s decision theory of statutory interpretation.260 Nourse posits that interpreters should understand and analyze legislative history in light of Congress’s own rules. She argues, “Just as no one would try to understand the meaning of a trial transcript without understanding the rules of evidence or civil procedure, no one should try to understand legislative history without understanding Congress’s own rules.”261 For example, Nourse describes the “conference rule,” which stipulates that conference committees cannot change the text of a bill when both the House and Senate have agreed to the same language.262 As a result, if a conference committee changes the text, interpreters should resolve doubts about the meaning of the statutory text in favor of the text that both houses passed.263 While Nourse focuses on the rules governing the legislative process after a bill has been introduced, the drafting manuals bring to fore the procedures and practices governing the bill-drafting process. The information in the drafting manuals about the operation of the drafting offices could thus help interpreters understand legislative history materials from the bill-drafting stage.

A limitation on this use of the drafting manuals is that courts may not know the extent to which the practices in the manuals are read and followed. Some of the practices described in the manuals, such as the drafters’ confidentiality and neutrality obligations, are prescribed by statute264 so it is likely that these are followed in practice. Other practices are not specifically mandated by statute but are key to the function and role of the drafting offices and are thus likely followed. For example, in In re Termination of Parental Rights to Quianna M.M., the Wisconsin Court of Appeals cited the Wisconsin LRB’s drafting manual’s directive that drafters “should not and cannot make the basic policy decision for the requester.”265 While this manual provision concerning the role of the drafter is not included in the LRB’s authorizing statute, it is central to the office’s ability to fulfill its statutory mandate to provide “drafting services equally and impartially.”266 It seems plain that the LRB could not fulfill this mission unless it adhered to the basic policy decisions of the legislator sponsoring the bill; if, instead, the drafters could make basic policy decisions, LRB would not be providing its drafting services “equally and impartially” as required by statute.

Other conventions described in the manuals appear to be more informal and, as a result, may not reflect actual practices. Therefore, an interpreter’s reliance on these manual provisions may be more problematic. For example, in his dissent in Monroe County v. Jennifer V., Judge Dykman of the Wisconsin Court of Appeals referred to the foreword to the Wisconsin drafting manual, which instructs bill drafters to communicate with the requesting legislator to ensure that both are using terms in the same way.267 Judge Dykman used this provision to support his plain meaning analysis. He reasoned that because legislative bill drafters are “trained to ask questions to ensure that legislation is clear,” it is “hard for me to accept that both a legislator and a bill drafting attorney would use the common, dictionary meaning for the word ‘conviction’ if they intended something different,” such as an unusual definition of the word.268 While the LRB cannot fulfill its statutory mission without adhering to the sponsor’s basic policy decisions, it is plausible that the drafters could nevertheless provide drafting services without consultation about the use of all terms in the bill. As a result, it seems problematic for an interpreter to rely on this provision in the Wisconsin manual to conclude that both the drafter and legislator had the same plain meaning understanding of a statutory term.