Small-Donor-Based Campaign-Finance Reform and Political Polarization

abstract. The communications revolution has led to a sudden, dramatic explosion in small-donor contributions to national election campaigns. In response, many political reformers, including most Democrats in Congress, have abandoned traditional public financing of elections and now advocate small-donor-based matching programs, such as those in which $6 of public funds would be provided to candidates for every $1 they raise from small donors. But the evidence suggests that online fundraising is subject to many of the same pathologies as the internet in general; the candidates who are most successful at small-donor fundraising are those who are able to generate national media coverage, often because they are more ideologically extreme or more able to create viral moments. Before adding further fuel to the fires of our hyperpolarized era, we need more discussion about the costs, as well as the benefits, of basing public financing on small-donor matching programs rather than more traditional forms of public financing.

Introduction

In an initial flush of romantic enthusiasm, social media and the communications revolution were thought to herald a brave new world of empowered citizens and unmediated, participatory democracy. Yet just a few years later, we have shifted to dystopian anxiety about social media’s tendencies to fuel political polarization, reward extremism, encourage a culture of outrage, and generally contribute to the degradation of civic discourse about politics.1 But when it comes to the campaign-finance side of democracy, the internet and the communications revolution are still being celebrated as an unalloyed good. The time has come to ask harder questions about this disconnect between how we view the internet’s effects on public discourse and its effects on fundraising.

In just the last several years, the communications revolution has dramatically begun to change the way campaigns raise money. By minimizing the transaction costs of reaching out to potential donors and of contributing to campaigns, the internet has empowered “small donors” (those who give under $200)2 as a major new force in democratic politics. At least among political-reform groups and much of the Democratic Party, this development is viewed as an unqualified good. Small donors are seen as purifying forces who will reduce political corruption and the influence of large donors, make politics more responsive to the “average” citizen, and encourage more widespread political participation. Thus, while we now worry about whether democracy writ large can survive the internet,3 many think the internet can guide us toward salvation when it comes to the role of money in elections.

Moreover, the Democratic Party’s vision of campaign-finance reform is now built upon this suddenly emerging role of the small donor. The first bill House Democrats passed in the new session of Congress, H.R. 14 (euphonically entitled the “For the People Act of 2019”), which is devoted to political reforms in general, proposes that candidates for Congress receive a six-to-one dollar match in public funds for all private small-dollar contributions under $200. In other words, the bill would turbocharge small donations by turning a $200 private contribution into $1,400 for the candidate (the match tops out at a certain level).5 As this bill demonstrates, small-donor-based public funding has now eclipsed more traditional forms of public financing as the sun around which Democrats believe campaign-finance reform should revolve. In addition, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) has made a candidate’s number of unique small donors one of the two factors now used to determine who qualifies for the primary debates.6

This Essay seeks to raise some concerns about the effects of small donors on politics, particularly about building campaign-finance reform around them. Part I describes the ways in which the communications revolution is reshaping our privately financed campaign system. Part II then presents the evidence to date that suggests small donors tend to fuel more ideologically extreme candidates. Finally, Part III identifies specific aspects of H.R. 1’s design that ought to be discussed more widely. Put most broadly, the question posed here is whether the concerns that have emerged about the internet and democracy should suddenly disappear when it comes to fundraising, or whether we need to reflect more on how those same concerns might also apply to the internet’s empowerment of small donors.

I. the sudden and dramatic rise of small donors

For all the attention small donors have recently received in the early stages of the 2020 presidential campaign process and in Democratic Party circles, it is important to recognize that our experience with how small donors might affect campaigns—particularly outside the presidential context—is quite recent and very limited. At the national level, prior to the 2018 midterm elections, small donors had played a significant role only in presidential elections.

Howard Dean, in his 2004 campaign, was the first presidential candidate to exploit the internet’s fundraising potential,7 but it was Barack Obama who convincingly demonstrated this power, particularly for raising money from small donors. In the 2008 general election, he raised about 24% of his funds from small donors; in the 2011-12 cycle, he raised about 28% of his funds from small donors (by comparison, Mitt Romney’s small-donor total was 12%).8 Obama’s ability to raise money from individual donors, large and small, was the main reason he was the first major-party candidate to abandon public financing for his 2008 general election campaign—which effectively destroyed the public-financing system for presidential elections by leading all subsequent nominees to opt out of public financing as well.9 The general-election public grant would have provided Obama about $84 million but capped his fundraising at that amount; by opting out, he managed to raise over $300 million instead during the same period.10 As a result, Obama massively outspent his Republican opponent, John McCain.11 In 2016, Donald Trump became the most successful candidate ever in raising money from small donors, whether measured in total dollars raised or as a percentage of his overall fundraising. Small-donation dollars made up 69% of the individual contributions to Trump’s campaign and 58% of the campaign’s total receipts.12

But outside the high-profile context of presidential campaigns, small donations played a minor role until 2018. In 2016, small donors accounted for only about 6% of the money raised by House candidates.13 This changed dramatically just two years later, especially for Democratic candidates. Overall, Democratic Senate candidates raised 27% of their money from small donors; House Democratic candidates raised 16%.14 One of the major reasons for this leap was the creation and maturation of a Democrat-supporting, web-based platform called ActBlue.15 ActBlue enables donors to go to a single website, enter and store their personal information, then donate to any Democratic candidate (or progressive organization) that uses ActBlue—and to return to the website to donate over and over again, to different candidates or causes.16 More than half the individual contributions to Democratic House and Senate candidates in the 2018 election cycle were given through ActBlue.17 Almost half these donations come via smartphones.18 In the 2018 election cycle, ActBlue facilitated nearly $1.6 billion dollars in donations for Democratic candidates and causes overall—an astounding 80% increase from four years earlier, with the average donation being around $39.50.19 By summer 2019, ActBlue donors had given 68% more money than they had by the same time in 2018—with the average donation being $32.20

Mostly as a result of ActBlue, Democratic Senate and House candidates outraised Republicans more than two-to-one in individual contributions in 2018.21 Republicans are now trying to catch up by creating a parallel website called WinRed.22

This recent revolution in small-donor financing has been almost universally celebrated by political “reform” groups and others troubled by the role of money in elections. Given the constraints Buckley v. Valeo23and its progeny impose on spending caps, small-donor financing appears to be a way of reducing the role of large donors, not by regulatory attempts to cap their donations, but by diluting their significance. The internet’s facilitation of small-donor financing increases the overall amount of money in elections and the percentage that comes from small donors. To reformers, small-donor contributions provide a constitutionally unproblematic path to a more egalitarian and participatory system of financing, and a countervailing force against what they see as the corrupting force of special interests or “big donors.” Indeed, the sudden power of small-donor money has been described in glorious terms: as a way to “reclaim” our republic,24 a development which would not only “significantly enhance the quality of democracy in the United States”25 but also “restore citizens to their rightful pre-eminent place in our democracy.”26

The sudden rise of small donors is an organic development that has grown out of the creativity of campaigns and intermediary organizations like ActBlue in recognizing how the internet can change fundraising and other aspects of democratic politics. But the Democratic Party now wants to turn this development into a foundation for party policy and public policy. As to the former, the party is now using small-donor participation rates as a means of determining which Democratic presidential candidates will be featured in the all-important primary debates. The DNC has set debate-participation requirements based on just two criteria: how well a candidate is performing in certain polls and/or whether they have met a threshold for unique donor contributions.27 As a result of the small-donor contribution requirement, some candidates—including wealthy candidates who could otherwise self-fund their entire campaign—now plead with donors to give them just $1 or $5 to increase their number of unique small donors.28 Indeed, this rule has created an inefficient incentive system in which some candidates were spending $55 to attract each new $5 donor.29 As this example demonstrates, the small-donor requirement has driven up the cost of campaigns; the cost of soliciting a small donation might be the same as soliciting a larger donation, but the more money campaigns are required to raise in small increments—to reach the required thresholds of unique small donors—the more the cost of fundraising increases.30

The DNC rules did not, by contrast, give any weight to the total amount of funds raised, whether someone had held public office and for how long, or any other possible ways of determining the candidates most appropriate for entry into the major debates. The relatively obscure but internet-savvy entrepreneur Andrew Yang and the idiosyncratic Representative Tulsi Gabbard met the 130,000-donor requirement for the all-important September debate (as did eight others), while senators like Michael Bennet and Kirsten Gillibrand, as well as governors like Steve Bullock, Jay Inslee, and John Hickenlooper, did not.31 Is it churlish to wonder whether a criterion that elevates a candidate like Andrew Yang over senators and governors is a sensible basis for winnowing the field?

As demonstrated in the above discussion of H.R. 1, the Democratic Party has also begun using small donors as the foundation on which to build campaign-finance reform. Keep in mind that these reforms only affect the contribution side of campaign finance—who contributes to candidates and how much. Because the Supreme Court has held that independent spending is constitutionally protected, Congress cannot impose caps on it. I now turn to some concerns about whether this rush to celebrate small donors and turn them into the backbone of campaign-finance reform is in fact as unalloyed a good as the unqualified enthusiasm of current campaign-finance reformers suggests.

II. small donors and polarization

Small-donor financing is part of the general trend toward using the communications revolution to bypass traditional intermediaries in politics and enhance direct modes of citizen participation. But, amid the current enthusiasm about the rise of the small donor, an issue that has received too little attention is whether small donors fuel the ideological extremes in our politics—and thus, whether building campaign-finance reform around them will further accelerate our hyperpolarized politics. If so, policy reformers will have to judge how to weigh the benefits of small-donor financing against the cost of ever-increasing polarization.

As a starting point, it is important to recognize that individuals who donate to campaigns tend, in general, to be considerably more ideologically extreme than the average American. This is one of the most robust empirical findings in the campaign-finance literature, though it is not widely known. The ideological profile for individual donors is bimodal, with most donors clumped at the “very liberal” or “very conservative” poles and many fewer donors in the center, while the ideological profile of other Americans is not bimodal and features strong centrist representation.32 This fact follows from the underappreciated general logic of political participation in the United States, which is that those who participate most actively tend to be more ideologically extreme than those who participate less.33 Indeed, donors are even further to the liberal or conservative poles than primary voters.34

Against this backdrop, the issue is whether small donors will be just as ideologically extreme as other individual donors, less so, or more so. Thus far, the limited evidence available does not suggest that small donors are any less ideologically extreme than other donors. Indeed, some evidence suggests they are more so.35 In one major study, small donors were found to contribute more to ideologically extreme candidates than did other individual donors.36 Other studies conclude that the most ideologically extreme incumbents raise dramatically more from small donors than more moderate incumbents; indeed, these studies find that an incumbent’s ideological extremism has three times greater an effect on small-donor contributions than does the competitiveness of the election.37 Work that tries to get directly at the motivations for giving concludes that small donors are even more motivated by ideological considerations than larger donors.38 To be sure, some work denies that small donors favor the ideological extremes any more than large donors,39 and the recent, rapid increase in small-donor contributions means we do not yet know whether prior data about the relationship between polarization and small donors will remain relevant as small-donor financing becomes more widespread—if it does, in fact, continue to be as widespread after our current moment of existential politics passes.

But it is not hard to see why the relationship would persist. Especially when we get away from the most visible races, such as presidential elections, if one asks what types of candidates are most likely to attract large flows of small donations from around the country, it is easy to understand why candidates who are the most visible or attract a devoted core of supporters would be most successful at raising small donations. Those candidates tend to come less from the center than from the poles of the political spectrum. This is much like the experience with pre-internet, direct-mail fundraising, in which the most extreme appeals generated the most money, and in which more ideologically extreme candidates benefitted the most.40

In addition, small-donor contributions, like much else on the internet, appear to be fueled by viral moments, outrage, and the culture of celebrity. The algorithmic structures of the social media giants, which prioritize and fuel “engagement,” already reward candidates who emphasize controversy to drive clicks. As one recent essay put it, “Facebook’s algorithm . . . [is] providing our most divisive politicians with . . . a bottomless pool of attention”—and the ability to raise money off that attention.41 This, too, should give us pause about whether we want to base public financing on such a foundation. One of the Democratic candidates running for President, Senator Michael Bennet, described the way the need to raise money online these days is part of what pushes candidates toward more extreme positions: “The equities that are being satisfied are the responses that you get on social media and your ability to raise money on the internet. . . . [T]he more extreme you are, the more rewarded you are.”42 As we gain more experience with the DNC small-donor debate requirements, more candidates are making the same observation.Thus, former Representative John Delaney recently remarked:

If you need to raise a dollar online, you don’t talk about bipartisan solutions. . . . You talk about extreme partisan positions. . . . If I were to post something about getting rid of the Electoral College, it would do really well on social media among Democratic activists. If I were to post something about expanding early childhood education, and talking about a bipartisan way to make that happen, it would go over like a thud on social media. No one cares. So the feedback loop really encourages people to run on things that are more extreme.43

You can take these observations as those of disappointed candidates who are struggling or as the insights of insiders experienced with the ways today’s presidential campaign process actually works.

As a New York Times article regarding the presidential nomination process put it after analyzing six years of online donations, “the art of inspiring online donors is very much about timing: It’s about a moment in the national spotlight—and then capitalizing on it.”44 One example was Senator Cory Booker’s “I am Spartacus” moment, which was mocked, but which led the next day to his second-best day of small donations to that point.45 Similarly, the day after Senator Mitch McConnell chastised Senator Elizabeth Warren on the Senate floor, saying “she persisted” after being warned, Senator Warren received 27,000 online donations, two-and-a-half times more than on her best day since 2013.46 When President Trump went to Nevada during the Senate race and called the Democratic candidate, Representative Jacky Rosen, “Wacky Jacky,” the next week Rosen collected one-third of all the small-donor money she received that entire fundraising quarter.47 Do we want to dramatically amplify these moments by providing $6 in public funds for every $1 raised in these ways?

To determine which candidates would benefit most, relative to others, from public funds that match small-dollar contributions, we can examine which candidates have been the most dependent on small donors in recent years. The best metric is which candidates raised the highest percentage of their overall individual contributions from small donors. From earlier races, we know that some of the most successful small-donor fundraisers in the past were Representatives Michele Bachmann and Allen West, both of whom can safely be characterized as among the more inflammatory Republicans, from the Tea Party wing of the party, while in office.48

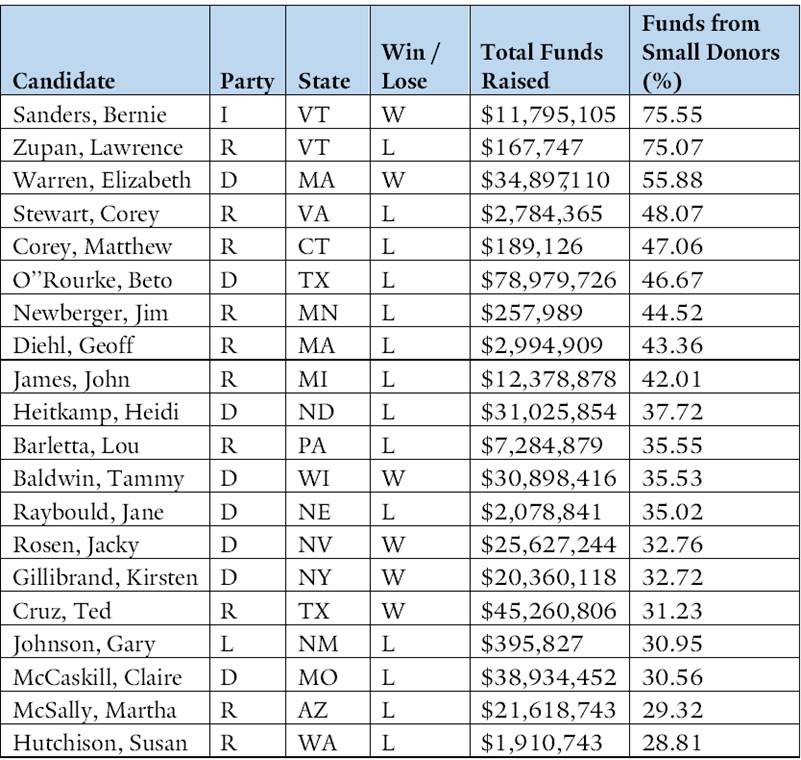

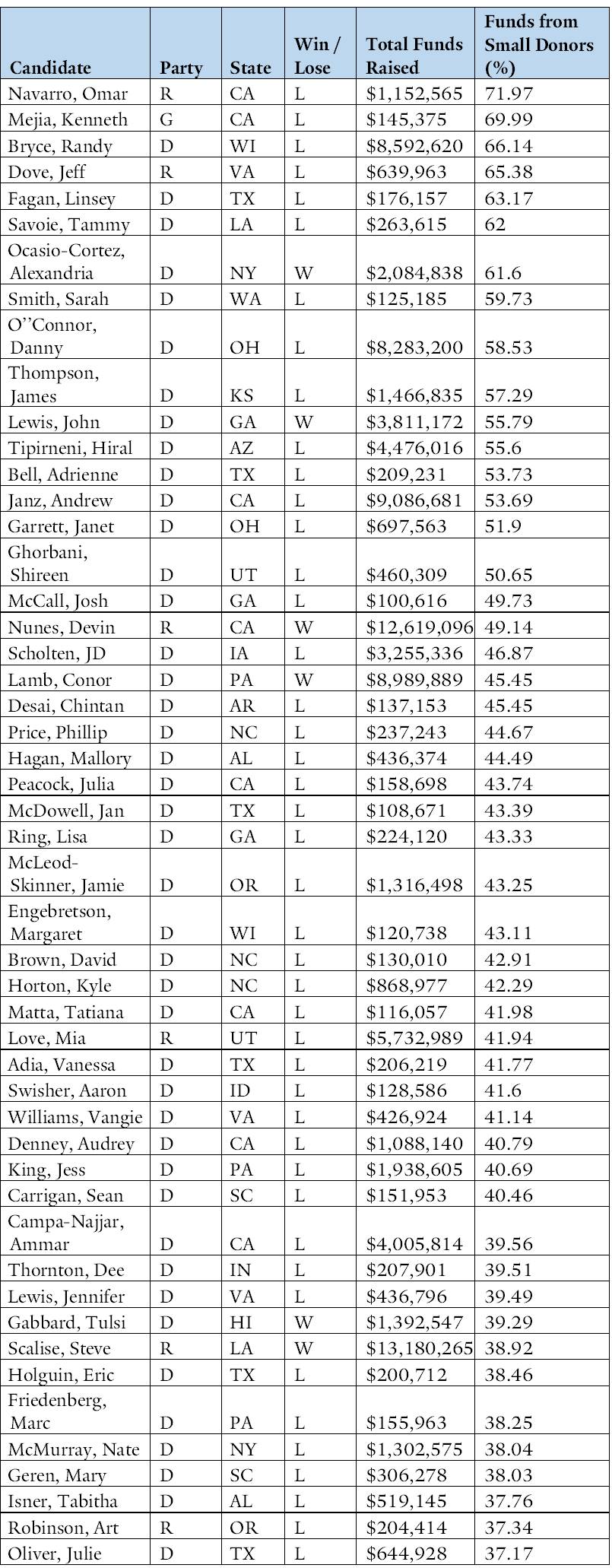

In the most recent midterms, on the Senate side, the three candidates who raised the highest percentage of their individual donations from small donors were Senator Bernie Sanders (76%), Lawrence Zupan (75%), a virtually unknown real-estate broker who ran as a Republican against Sanders, and Senator Elizabeth Warren (56%).49 As the Appendices to this Essay document, of the twenty Senate candidates most dependent on small donors, six won election, with Senators Baldwin, Rosen, Gillibrand, and Cruz joining Sanders and Warren. Of the fifty House candidates in 2018 who raised the highest percentage of individual contributions from small donors and raised a total of at least $100,000, only six were elected. From highest to lowest percentage of small-donor funding, they were Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D), who burst onto the scene after defeating in the primaries a member of the House leadership; John Lewis (D), the iconic civil-rights figure; Devin Nunes (R), Chair of the House Intelligence Committee and a regular defender on cable television of President Trump; Conor Lamb (D), whose isolated special election received enormous national media coverage; Tulsi Gabbard (D), whose political positions resist being characterized in a phrase; and Steve Scalise (R), the Republican House whip who received massive media coverage after being shot in the fall of 2017 and who raised more in the first quarter of 2018 than any other House whip in a comparable period.50 On the Democratic side, where most small money has flowed so far, this suggests that a six-to-one matching program would tend to empower the Sanders-Warren-AOC wing of the Democratic Party, along with those in extremely high-profile races (the special election Lamb won) or exceptionally well-known figures (Lewis). Do moderate Democrats recognize that and support this approach nonetheless?

On the Republican side, those candidates who have received exceptional media attention (Nunes, for leading Trump’s defense, and Scalise, after being shot) have fared the best with small donors. Moreover, we are witnessing a massive, recent surge in small-donor financing at a moment when politics seems, to many people, existential. We do not know how much small-dollar money will flow, particularly outside presidential elections, if our politics returns to a more “normal” state. Building campaign-finance reform on the assumption that small donations will continue at the same magnitude or higher as the last few years would weaken public financing if small donations become a smaller percentage of contributions in the future.

Most discussions of small-donor-based public financing implicitly compare it to the status quo, which is our purely private system of campaign finance. But we should keep more traditional forms of public financing in mind as well. With traditional public financing, the funds come from general revenues, so the source of funds is politically agnostic. But with virtually no discussion of traditional public financing or whether small-donor matching funds would reward celebrity stature, media visibility, and the ideological extremes, Democrats (at least in the House) have wholeheartedly embraced small-donor matching funds as their new vision of campaign-finance reform.

III. questions about current proposals for a national small-donor matching program

H.R. 1 would massively subsidize the role of small donors in American elections. H.R. 1 is messaging legislation, not something its proponents believe would actually be enacted in this Congress. Partly for that reason, House Democrats unanimously voted for it without specific provisions receiving extended analysis or discussion. I want to raise briefly here two features of H.R. 1 that warrant further consideration if legislation of this sort becomes a serious prospect in future Congresses.

First, although H.R. 1’s public financing proposal is modeled on New York City’s small-donor matching program, there is one highly significant difference. New York City’s program only matches small-donor contributions from city residents (like the federal program, New York had provided a six-to-one match, although voters in 2018 approved raising it to eight-to-one).51 But unlike the New York City program, H.R. 1 does not limit its matching funds to contributions from those who are residents of the House district at issue.52

When it comes to reducing the polarizing effects of multiplying small donations with a six-to-one match, this is a consequential choice. From a realpolitik perspective, it is easy to understand why House Democrats would not want to limit matching funds to in-district contributions. These days, a substantial percentage of House candidates’ funds from individual contributors come from out of state. This is a reflection of the greater nationalization of elections,53 as well as the greater national interest in individual House races when partisan control of the House is perceived to be up for grabs.54 In a major study of the 2004 elections, the average congressional district received contributions from seventy other districts, while in 1996, the figure had only been fifty-five.55 By 2004, a majority of individual contributions came from district residents in fewer than 20% of congressional districts.56 In nearly the same percentage of districts, outside money constituted 90% or more of the candidates’ individual contributions.57 Moreover, this money is mostly not coming from those who live in nearby districts, but from people living in a relatively small number of geographically distant areas, such as wealthy parts of New York, Los Angeles, Florida, Chicago, Maryland, New Jersey, Atlanta, and others.58 Indeed, 5% of congressional districts in this 2004 analysis provided more than 25% of all non-local money; a mere 20% of congressional districts provided a majority of the outside money.59 More recent work reaffirms this and concludes that the average House member receives just 11% of individual contributions from in-district donors, while donors come overwhelmingly from a small number of metropolitan areas, such as those noted above.60

Moreover, it is hardly surprising that members who receive the most money from outside their districts are more ideologically extreme than their party’s other representatives.61 Indeed, even for members who represent moderate districts, if they receive more than $353,000 in outside funds, they vote in ways characteristic of the party’s ideological wing rather than the preferences of their more moderate constituents.62 Money that flows from New York and California to House districts across the country is almost inevitably going to reflect more nationalized, ideological motivations than in-district money. Out-of-state money will flow to those with the highest national profile, and those figures are not likely to be moderates. As one academic expert puts it, “all that outside funding may be leading to a more polarized Congress, as it appears to encourage members to pay attention to donors whose ideologies are more extreme than voters.”63

To reduce the polarizing effects of individual contributions, a national small-donor matching bill could limit public matching funds to small-donor contributions from district residents. A direct ban or limit on the aggregate amount of out-of-district campaign contributions from American citizens would almost certainly be unconstitutional.64 But the constitutional question is considerably different when the government is subsidizing elections and deciding, on non-viewpoint-based grounds, that it wants to match only in-district contributions, for legitimate public policy purposes such as increasing local representatives’ responsiveness to their constituents.65 Limiting matching funds to district resident contributions would reduce the effects of the currently proposed matching program in stoking the fires of polarization. But because few individual contributions come from within the district, such a limitation would also mean the matching program would be limited in overall effect and would not provide as strong a countervailing force against the weight of larger individual contributions (or against outside spending, as well).

We thus see a tradeoff between competing democratic goals: for a national matching funds program to have a large overall effect, it must match out-of-district contributions, but since out-of-district small donations are even more ideologically driven than in-district ones, such a program is also likely to enhance polarization. Once again, the contrast is not with our current system of privately financed elections. The issue is, if we are going to have public financing, what form should it take? In more traditional public financing, such as that used in several states, government provides grants of various sizes, once a candidate raises a threshold amount from a minimal number of donors. Because these public funds come from the general treasury and are not pegged to the number of individual donors or amounts raised from them, the “donor” (that is, the general treasury) is politically agnostic as among types of candidates.66

Other features of H.R. 1 also warrant further discussion. The bill, for example, specifically permits an individual to give small donations to as many candidates as desired, with each donation receiving the six-to-one match.67 For donors motivated primarily by the desire to maximize their party’s partisan advantage in the House, rather than by the merits of any particular candidate, there is an incentive to break up their contributions into $200 chunks to be spread across many candidates. At the extreme, that means an individual could give $200 to 435 candidates, for a total of $87,000. Since all of these donations would receive a six-to-one match, that would turn this $87,000 into contributions worth a total of $522,000.68

Until the Supreme Court’s 2014 decision in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission,69 federal law imposed an aggregate cap of $46,200 on the total amount an individual could give to federal candidates. When the Supreme Court struck this cap down as unconstitutional, many campaign-finance-reform advocates decried the decision. Yet under H.R. 1’s matching funds, an individual who gives just $7,800 in small donations to thirty-nine candidates would, effectively, be able to exceed the $46,200 cap struck down in McCutcheon. And in the extreme, and admittedly unlikely, example above, H.R. 1 would enable an individual “small donor” contributor to effectively provide more than $500,000 to candidates—more than ten times the total amount of money that federal law permitted before McCutcheon. For reformers who believe the $46,200 aggregate cap was an important means to avoid corruption or undue influence, should similar concerns arise about public financing that gives individual donors enough weight to vastly exceed that limit? Perhaps the answer is that, if many more people can now give, in effect, far more than the pre-McCutcheon aggregate cap, the impact of such contributions would be diluted and potentially less influential or corrupting. Or perhaps the view is that, if McCutcheon is the law, small donors should be able to take advantage of it.

Once again, the absence of any aggregate cap in the proposed matching program is unlikely to rest on constitutional concerns. Because the government is providing public funds, it has some latitude in determining the scope of the program. That makes surprising the absence of any discussion at all of whether there ought to be an aggregate cap on the total amount of a candidate’s small donations eligible to receive a six-to-one public funding match. Of course, if any legislation restricted matching funds to only in-district contributions, that restriction would automatically address any questions about the aggregate effects of matching an unlimited number of small-dollar contributions.

Finally, the identities of those who give $200 do not currently have to be disclosed. But under H.R. 1, a $200 contribution now becomes a $1,400 contribution. As a result, should the identities of these “small” donors then have to be disclosed? My own view is that, as a general matter, we ought to increase the level at which disclosure of individual identities is required; the $200 threshold has been in place since the 1970s. Given how expensive modern campaigns have become since then, there is no risk that contributions will corrupt anyone at relatively low levels that are still considerably higher than $200; at the same time, in our intensely charged political environment, we have become more aware of the abusive ways in which this information has been used. We ought to protect people’s political contributions, just as we protect their vote, up to the point at which there are significant informational or anti-corruption justifications for disclosure. Today, that point is well north of $200, certainly for presidential races and probably for all national elections. But as long as we continue to require the disclosure of any contribution over $200, consistent policy would seem to dictate that if the identities of $1,200 contributors must be disclosed, the same would be true of small donors whose donations are of $1,200 value to the campaigns.

Conclusion

The design of a democratic system seeks to realize a number of different values. Most regulations of the political process, including those styled as political “reforms,” actually implicate tradeoffs and conflicts among these values. Yet the staunchest advocates of reform typically present their preferred reforms as unmitigated goods and frequently fail to recognize or confront the reality of these tradeoffs. Advocates so focused on the one dimension of a problem that most concerns them can develop tunnel vision that obscures the costs of their reforms along other dimensions of democracy. Small-donor financing has burst onto the national scene as a major force only in the last few years, which makes the current unbridled enthusiasm for it understandable but potentially troubling, to the extent we ignore the full range of consequences of turning it into the exclusive basis for using public funds to finance elections.

Before we restructure public financing around a small-donor matching program, we need more clear-eyed analysis and discussion of whether doing so will increase ideological extremism and polarization. If fundraising in the age of the communications revolution is subject to the same dynamics as current democratic discourse on the internet more generally, small-donor matching programs for national elections might require us to confront difficult choices. How should the benefits of small-donor matching programs—such as enhancing participation, counterbalancing the influence of large donors, and reducing political corruption—be weighed against the costs of turbocharging the more ideological poles in American politics? For many years, I have argued that we should not underestimate the costs of hyperpolarized political parties, particularly in the American separated-powers system.70 Such a structure of political parties makes the political process unable to deliver on the issues that voters report caring about most, which in turn risks disaffection, alienation, and perhaps even rejection of the democratic process itself.71

The organic development of small-donor funding through the internet is not the issue. Like most genies, this one cannot be put back in the bottle. The issue is whether to transform that development into the foundation of public financing. Almost overnight, small-donor-based public financing has crowded out any discussion of more traditional public financing—a system with which, unlike matching programs, we already have meaningful experience at the statewide level in several states. Traditional public financing must confront its own implementation issues, to be sure, as well as political resistance. But the general-treasury money in traditional public financing does not come from those who are most intensely engaged in politics. That might be a significant advantage, in the overall democratic calculus, of more traditional forms of public financing over public financing structured as a small-dollar matching program. In our already hyperpolarized democratic era, we need a robust public discussion over which forms of public financing best serve the full range of our democratic values.

Sudler Family Professor of Constitutional Law, NYU School of Law. I want to thank my research assistants, Elaine Andersen (NYU) and Soren Schmidt (Yale), for excellent research assistance.

APPENDIX A. top twenty senate candidates most dependent on small donors, 2018 election72

|

Appendix B: Top Fifty House Candidates Most Dependent On Small Donors, 2018 Election73

|

The term “small donors” is typically pegged to the requirements in federal election law. For those who give $200 or less (in total) to federal campaigns, the campaigns are not required to disclose identifying individual information. See Federal Election Campaign Act, 52 U.S.C. § 30102(c) (2018) (requiring that contributions greater than $200 be individually recorded).

See id. § 5111 (“The aggregate amount of payments made to a participating candidate with respect to an election cycle under this title may not exceed 50 percent of the average of the 20 greatest amounts of disbursements made by the authorized committees of any winning candidate for the office of Representative in, or Delegate or Resident Commissioner to, the Congress during the most recent election cycle, rounded to the nearest $100,000.”).

For the first two debates, candidates had to meet the polling requirements or obtain contributions from 65,000 unique donors, with a minimum of 200 donors in at least twenty states. For the third debate, in September, participation required meeting the polling requirements and obtaining contributions from 130,000 unique donors. Press Release, Democratic Nat’l Comm., DNC Announces Details for the First Two Presidential Primary Debates (Feb. 14, 2019), https://democrats.org/news/dnc-announces-details-for-the-first-two-presidential -primary-debates [https://perma.cc/TFT3-6MPS]; Press Release, Democratic Nat’l Comm., DNC Announces Details for Third Presidential Primary Debate (May 29, 2019), https:// democrats.org/news/third-debate [https://perma.cc/3B6F-YR6W].

Dean raised about 40% of his money online. See Michael J. Malbin, Small Donors: Incentives, Economies of Scale, and Effects, 11 Forum 385, 391-92 (2013); Bill Scher, 4 Ways Howard Dean Changed American Politics, Week (June 21, 2013), https://theweek.com/articles/462922 /4-ways-howard-dean-changed-american-politics [https://perma.cc/VH7U-KPE5].

Press Release, Campaign Fin. Inst., Money vs. Money-Plus: Post-Election Reports Reveal Two Different Campaign Strategies, tbl.4 (Jan. 11, 2013), http://www.cfinst.org/press /releases_tags/13-01-11/Money_vs_Money-Plus_Post-Election_Reports_Reveal_Two _Different_Campaign_Strategies.aspx [https://perma.cc/6FGZ-QWZE] (comparing Obama and opponents in 2008 and 2012 elections).

See Michael Luo, Obama Hauls in Record $750 Million for Campaign, N.Y. Times (Dec. 4, 2008), https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/05/us/politics/05donate.html [https://perma.cc/9H3X -AWRG] (estimating that Obama raised over $300 million during the relevant period); Michael Luo & Jeff Zeleny, Obama, in Shift, Says He’ll Reject Public Financing, N.Y. Times (June 20, 2008), https://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/20/us/politics/20obama.html [https:// perma.cc/P823-J2BJ].

Luo, supra note 9; see Tahman Bradley, Final Fundraising Figure: Obama’s $750M, ABC News (Dec. 5, 2008), https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/Vote2008/story?id=6397572 [https:// perma.cc/XM9C-PY27].

Press Release, Campaign Fin. Inst., President Trump, with RNC Help, Raised More Small Donor Money than President Obama; As Much as Clinton and Sanders Combined (Feb. 21, 2017), http://www.cfinst.org/Press/PReleases/17-02-21/President_Trump_with_RNC _Help_Raised_More_Small_Donor_Money_than_President_Obama_As_Much_As _Clinton_and_Sanders_Combined.aspx [https://perma.cc/SC3F-DAM6].

Michael J. Malbin & Brendan Glavin, CFI’s Guide to Money in Federal Elections: 2016 in Historical Context tbls. 2-8, Campaign Fin. Inst., (2018), http://www.cfinst.org/pdf/federal /2016Report/CFIGuide_MoneyinFederalElections.pdf [https://perma.cc/BQ2L-XDTJ].

Blue Wave of Money Propels 2018 Election to Record-Breaking $5.2 Billion in Spending, Ctr. for Responsive Pol. (Oct. 29, 2018), https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2018/10/2018 -midterm-record-breaking-5-2-billion/ [https://perma.cc/2ET6-P39K].

See Carrie Levine & Chris Zubak-Skees, How ActBlue Is Trying to Turn Small Donations into a Blue Wave, FiveThirtyEight (Oct. 25, 2018), https://fivethirtyeight.com/features /how-actblue-is-trying-to-turn-small-donations-into-a-blue-wave [https://perma.cc/ D9CP-VPN9].

See How Does ActBlue Work?, ActBlue, https://support.actblue.com/donors/about-actblue /how-does-your-platform-work [https://perma.cc/9EUY-5CFD].

2018 Election Cycle in Review, ActBlue, https://report.actblue.com [https://perma.cc/GZ5H-HV86].

Id.; see Lisa Lerer, ActBlue, the Democrats’ Not-So-Secret Weapon, N.Y. Times (Nov. 16, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/16/us/politics/on-politics-actblue-democrats.html [https://perma.cc/MQD4-XAKJ].

Emily Dong & Dave Stern, Q1 2019: Strongest Start to an Election Cycle on ActBlue, ActBlue (Apr. 17, 2019), https://blog.actblue.com/2019/04/17/q1-2019-strongest-start-to -an-election-cycle-on-actblue [https://perma.cc/WDQ9-2M6H]; see Emily Dong & Zoe Howard, No Ceiling to Small-Dollar Donor Engagement, ActBlue (July 17, 2019), https://blog.actblue.com/2019/07/17/no-ceiling-to-small-dollar-donor-engagement [https://perma.cc/CV5Y-STGZ] (reporting Q2 2019 fundraising results and comparing with previous years).

Carrie Levine & Peter Overby, Red Shift: How Republicans Plan to Catch Democrats in Online Fundraising, NPR (July 1, 2019), https://www.npr.org/2019/07/01/736990455/red-shift -how-republicans-plan-to-catch-democrats-in-online-fundraising [https://perma.cc/S6SW -NDPC]; Levine & Zubak-Skees, supra note 15.

See Alex Isenstadt, GOP to Launch New Fundraising Site as Dems Crush the Online Money Game, Politico (June 23, 2019, 8:01 PM), https://politico.com/story/2019/06/23/republicans -win-red-2020-1377058 [https://perma.cc/B7ZV-SHL7]. One difference is that WinRed will be a for-profit entity, while ActBlue is not. See Michelle Ye Hee Lee & Michael Scherer, GOP Launches New Fundraising Platform to Capitalize on Republican Small-Dollar Donor Base, Wash. Post (June 24, 2019), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/gop-launches-new -fundraising-platform-to-capitalize-on-republican-small-dollar-donor-base/2019/06/24 /0bfd29fc-968b-11e9-8d0a-5edd7e2025b1_story.html [https://perma.cc/4K3W-FD5U].

Lawrence Lessig, We the People, and the Republic We Must Reclaim, Ted (Feb. 2013), https://www.ted.com/talks/lawrence_lessig_we_the_people_and_the_republic_we _must_reclaim [https://perma.cc/TG6S-UHDR].

Anthony J. Corrado et al., Reform in an Age of Networked Campaigns: How to Foster Citizen Participation Through Small Donors and Volunteers, Campaign Fin. Inst. 53 (2010), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/0114_campaign_finance _reform.pdf [https://perma.cc/C5LW-KNR3] (joint report from the Campaign Finance Institute, American Enterprise Institute, and the Brookings Institution).

Adam Skaggs & Fred Wertheimer, Empowering Small Donors in Federal Elections, Brennan Ctr. for Just. 23 (2012), https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy /publications/Small_donor_report_FINAL.pdf [https://perma.cc/2YNV-GAAN].

See Maggie Severns & Zach Montellaro, How Democratic Debate Rules Are Forcing a Billionaire to Plead for Pennies, Politico (July 29, 2019, 5:06 AM), https://www.politico.com /story/2019/07/29/tom-steyer-2020-campaign-fundraising-debates-1437754 [https:// perma.cc/6YWW-WYNL]. This sometimes leads to the amusingly inefficient situation of candidates spending far more than $1 to get a new $1 donor. See, e.g., Shane Goldmacher & Lisa Lerer, New Democratic Debate Rules Will Distort Priorities, Some Campaigns Say, N.Y. Times (May 30, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/30/us/politics/democratic-debate -rules.html [https://perma.cc/U794-6CHR] (“Two campaigns said digital vendors are currently quoting them prices of $40 and up to acquire a new $1 donor.”).

See Julie Bykowicz & Chad Day, Democratic Presidential Hopefuls Spent over $50 Million this Year to Raise More Money, Wall St. J. (Oct. 17, 2019, 5:30 a.m. ET), https://www.wsj.com /articles/democratic-presidential-hopefuls-spent-over-50-million-this-year-to-raise-more -money-11571304603 [https://perma.cc/4VJX-QDZB] (noting this was true of former Governor John Hickenlooper).

Maggie Astor, Who’s in the Next Democratic Debate? Less than Half of the Field, N.Y. Times (Aug. 1, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/01/us/politics/next-democratic-debate.html [https://perma.cc/C8PA-GM5V].

For some of the work documenting this, see, for example, Raymond J. La Raja & Brian F. Schaffner, Campaign Finance and Political Polarization: When Purists Prevail (2015); Michael J. Barber, Ideological Donors, Contribution Limits, and the Polarization of American Legislatures, 78 J. Pol. 296 (2016); Michael J. Barber et al., Ideologically Sophisticated Donors: Which Candidates Do Individual Contributors Finance?, 61 Am. J. Pol. Sci. 271 (2017).

Charlie Warzel, Could Facebook Actually Nuke Elizabeth Warren’s Campaign?, N.Y. Times (Oct. 10, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/10/opinion/trump-warren-facebook.html [https://perma.cc/HAM6-C7V7].

Tim Alberta, ‘Can Any of These People Beat Trump?,’ Politico (Oct. 17, 2019), https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2019/10/17/2020-democratic-debate-candidates -michael-bennet-229856 [https://perma.cc/6KDG-8RTL]. Bennet’s full quotation read as follows: “The equities that are being satisfied are the responses that you get on social media and your ability to raise money on the internet. And that has led to people offering up policies that—.” He stops himself again. “You know, when Obama ran in 2008, there was an outer edge, because that political market could only bear so much. But this political Twitter market can never bear too much; the more extreme you are, the more rewarded you are.” Id.“”

Gerald F. Seib, Delaney’s Complaint: Democrats’ Primary System Tilts Left, Wall St. J. (Oct. 28, 2019), https://www.wsj.com/articles/delaneys-complaint-democrats-primary-system-tilts-left-11572271810 [https://perma.cc/87KJ-QDRJ].

Shane Goldmacher, 6 Days When 2020 Democratic Hopefuls Scored with Small Donors, N.Y. Times (Feb. 9, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/09/us/politics/democrats -donations-2020.html [https://perma.cc/EF5K-ZXQJ].

See Julie Bykowicz, Democrats Outperforming Republicans in Small Donations, Wall St. J. (Sept. 5, 2018), https://www.wsj.com/articles/democrats-outperforming-republicans-in-small -donations-1536139801 [https://perma.cc/5NMQ-SXZ2].

See, e.g., Amy Bingham, Rep. Allen West Says Up to 81 House Members Are Communists, ABCNews (Apr. 11, 2012), https://abcnews.go.com/blogs/politics/2012/04/rep-allen-west-says-up-to-81-house-members-are-communists [https://perma.cc/T6KM-FMCG] (quoting West at a town hall, stating, “I believe there’s about 78 to 81 members of the Democratic Party that are members of the Communist Party”); Chris Cillizza, What Michele Bachmann Meant to Politics, Wash. Post: The Fix (May 29, 2013), https://www.washingtonpost.com /news/the-fix/wp/2013/05/29/what-michele-bachmann-meant-to-politics [https:// perma.cc/5FCW-2APC] (noting that Bachmann “was viewed by Republican Congressional leaders as a problem to be dealt with as opposed to someone with whom they could work or someone with a significant constituency within the House deserving of special attention”).

The data in this paragraph were compiled for this Essay and comes from the Center for Responsive Politics website. Ctr. for Responsive Pol., https://www.opensecrets.org [https://perma.cc/W7BD-5SXD].

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 3-702(3) (defining “matchable contribution” to mean a contribution “made by a natural person resident in the city of New York”); What’s New in the Campaign Finance Program, N.Y.C. Campaign Fin. Board, http://www.nyccfb.info/program/what-s -new-in-the-campaign-finance-program-2 [https://perma.cc/7G87-KBSC] (explaining change from six-to-one to eight-to-one matching system).

Anne Baker, The More Outside Money Politicians Take, the Less Well They Represent Their Constituents, Wash. Post: Monkey Cage (Aug. 17, 2016) [hereinafter Baker, Outside Money], https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/08/17/members-of -congress-follow-the-money-not-the-voters-heres-the-evidence [https://perma.cc/28SH -WZS2]; see also Anne E. Baker, Getting Short-Changed? The Impact of Outside Money on District Representation, 97 Soc. Sci. Q. 1096, 1105 (2016) (empirical study concluding that as House members’ “dependency upon outside funds grows, they also become ideologically polarized”).

The Supreme Court has never directly addressed the issue, but given the relevant precedents, scholars have consistently concluded such restrictions would be unconstitutional. See, e.g., Richard Briffault, Of Constituents and Contributors, 2015 U. Chi. Legal F. 29, 62; David Fontana, The Geography of Campaign Finance Law, 90 So. Cal. L. Rev. 1247, 1283 (2017). After his retirement, Justice Stevens suggested a constitutional amendment to do so. John Paul Stevens, Six Amendments: How and Why We Should Change the Constitution 59 (2014).

There is some conflict in the empirical literature on whether public financing has contributed to legislative polarization in the states that use it. Compare Seth E. Masket & Michael G. Miller, Does Public Election Funding Create More Extreme Legislators? Evidence from Arizona and Maine, St. Pol. & Pol’y Q. (2014) (finding no link), with Andrew B. Hall, How the Public Funding of Elections Increases Candidate Polarization (forthcoming) (draft dated Aug. 13, 2014) (finding link between polarization and public financing).

See H.R. 1, 116th Cong. § 5111 (2019) (“NO EFFECT ON ABILITY TO MAKE MULTIPLE CONTRIBUTIONS.—Nothing in this section may be construed to prohibit an individual from making multiple qualified small dollar contributions to any candidate or any number of candidates, so long as each contribution meets each of the requirements of paragraphs (1), (2), and (3) of subsection (a).”).

This total could be limited indirectly by other provisions of the bill, such as the one limiting the aggregate matching funds to any one candidate to a level that does “not exceed 50 percent of the average of the 20 greatest amounts of disbursements made by the authorized committees of any winning candidate for the office of Representative in, or Delegate or Resident Commissioner to, the Congress during the most recent election cycle, rounded to the nearest $100,000.” Id.§

On the causes and structure of political polarization today, see Richard H. Pildes, Why the Center Does Not Hold: The Causes of Hyperpolarized Democracy in America, 99 Calif. L. Rev. 273 (2011); see also Daryl H. Levinson and Richard H. Pildes, Separation of Parties, Not Powers, 119 Harv. L. Rev. 2311 (2006).

See generally Richard H. Pildes, Romanticizing Democracy, Political Fragmentation, and the Decline of American Government, 124 Yale L.J. 804 (2014) (noting evidence for the decline in the effectiveness of American government and the costs when democratic governments cannot address the major issues voters care about most).